On a visit to New York just before Christmas, our Art Editor Lucy Gordan visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art and spoke with European Sculpture Curator Dr. Wolfram Koeppe.

Dr. Koeppe, what exactly is your position at the Museum and how long have you worked here?

Dr. Wolfram Koeppe: My title is Marina Kellen French Curator in the European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Collection. I’ve been at the Met for 23 years. For the past five years one of my responsibilities has been overseeing the annual installation of the Museum’s Christmas tree and crèche. Our head collaborator of the installation is Denny Stone, Senior Collections Manager, European Sculpture and Decorative Art Collection.

Wolfram Koeppe, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, interviewed for this story. (Photos credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

What was your background before the Met?

I was born in Germany, in the State of Hesse, in the administrative region of Giessen, near the city of Wetzlar, the headquarters of Leica and Zeiss. I studied at Justus Liebig University in Giessen and got my Ph.D. at the Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich. Before coming to the Met, I was an Assistant Curator for Research at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Over the years I’ve organized many installations and exhibitions here. “Extravagant Inventions: The Princely Furniture by the Roentgens (2012-13)” and its catalog won several awards. My favorite period of art is Baroque, so the crèche fits in perfectly.

Can you give us a brief history of the Met’s crèche?

Mrs. Loretta Hines Howard began collecting crèche figures in 1925 on her honeymoon. At the time of her death in 1982, the Met’s crèche had some 200 figures. They were all made during the 18th century in Naples by the artisans Giuseppe Sammartino (1720-1793) and his pupils Salvatore di Franco, Giuseppe Gori, and Angelo Viva.

All the figures are made with finely painted terracotta heads; legs, arms, and wings carved from wood; and bodies of hemp and wire. No two are alike. For example, the some 50 angels we hang on the tree (hence its nickname “Angel Tree”), have different faces and clothing, and are carrying different objects. Besides the 22 cherubs and the 50 angels, below is the Nativity scene of some 70 figures, which together with the Holy Family represent its three main elements traditional to 18th-century Naples: adoring shepherds and their flocks, the Three Kings in procession, and colorful peasants and townspeople. Then in the background are some 50 animals and the architectural pieces: quaint houses, market stalls with food products, Roman ruins, and a typical Italian fountain. The several pieces of their base fit together and are numbered and tagged with where each figure should be placed. Therefore we don’t change the layout often.

Wasn’t Sammartino also a sculptor?

Yes, his first dated work (1753) is the spookily life-like marble Veiled Christ in the San Severo Chapel in Naples.

Why was 18th-century Naples such an important center for crèches?

During the 1700s, crèche figures were an obsession in Naples.

Wealthy families competed to see who could create the most impressive ones. When Don Carlos of Bourbon (the future Charles III of Spain) ruled Naples and Sicily from 1734-1769, he reputedly owned a crèche with almost 6,000 figures.

Did Mrs. Howard purchase all her crèche figures in Naples?

Many yes, but not all, because, thanks to Naples’ international royalty, Neapolitan crèches were given as presents to royalty all over Europe and thus their figures can appear on the antique market, not only in Naples and Sicily, but all over what was Roman Catholic Europe in the 1700s, plus New York, of course.

Did she purchase her figures all at one time?

No, she bought them over the years from antique dealers and at auctions.

Why did Mrs. Howard collect crèche figures and not, for examples, paintings, sculpture, and books?

A student of the Ashcan School of Robert Henri, Mrs. Howard was a respected landscape painter and portraitist. She had an art gallery of her own. She collected other things, but her passion was crèche figures.

When did she make her donation?

Her figures were first displayed here in 1957. During the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, some of her figures were displayed at the White House. She made her donation to the Met in 1964. Since then it’s been one of New York’s most cherished holiday attractions for tourists and residents. It was the first crèche — a Southern European Roman Catholic tradition — to be displayed under a Christmas tree — the Northern European tradition. (Of course the blue spruce tree has to be artificial). This year it will be on view from November 24 through January 6, Epiphany. As always its installation will be set up in front of the 18th-century Spanish choir screen from the Cathedral of Valladolid in the Museum’s Medieval Sculpture Hall (Gallery 305).

The annual installation is made possible thanks to the Christmas Tree Fund financed by private donors and Mrs. Howard’s Fund, an endowment, which also covers the conservation and possible additional purchases of figures and accessories.

Since Mrs. Howard’s death have you added to the crèche?

Very occasionally through donations, mostly of accessories. At auction an 18th-century figure in good condition with original clothes can bring up to $18,000.

What are your favorite figures of the Met’s crèche?

The Three Kings because of their magnificence and prominence. They probably were Mrs. Howard’s as well.

Besides the Met, what other museums are famous for their crèches?

The National Museum of San Martino, located in the once huge medieval monastery complex completed in 1368 on the top of the Sant’Elmo Hill overlooking Naples, is home among many other crechès to the presepe Cuciniello. It counts 162 people, 80 animals 22 angels, and 450 miniature items. The Bayerisches Nationalmuseum (Bavarian National Museum) in Munich, one of the most important decorative arts museums in Europe, where I started to love art and crèches, houses some 60 crèches made in Bavaria, the Tyrol, Naples, and Sicily between 1700 and the early 20th century. A large proportion of this collection belonged to Munich’s native-son banker Max Schmederer (1854-1917), who collected over the years like Mrs. Howard. Each year he opened his home and his collection to the public. Like Mrs. Howard’s crèche, his figures show the events of the Christmas story, but his also illustrate other Bible stories and parables.

I love to go to Naples at Christmastime because many churches put their marvelous crèches on display. Two temporary exhibitions of the best contemporary crèche artisans’ work also take place then.

Why did Mrs. Howard donate her figures to the Met and not to another museum?

Although she was born in Chicago (her father was a lumber millionaire) and had a home in Wyoming, she felt herself a New Yorker.

Did she give all her figures to the Met or did she keep some?

The family still has some. In 1949, in memory of her husband, she’d also given another 18th-century crèche of 68 figures to the Abbey of Regina Laudis, home of cloistered nuns, in Bethlehem, Connecticut. It was restored here at the Met.

After her donation, she collaborated with the Met in the crèche’s annual installation. Her daughter Linn Howard Selby assisted her. Now her grand-daughters artist Andréa Selby Rossi and Stephanie Selby help.

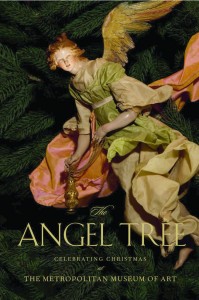

That’s right. In 1984 Linn published a book, The Angel Tree, about traveling with her mother to buy figures over the years and helping with the annual installation at the Met. It’s still available on Amazon and includes a history of crèche artisanry in Naples, of the Met’s crèche, thumbnail bios of its artisans, and how it is conserved.

Franco Artese’s Crèche at St. Patrick’s Cathedral

Thanks to the sponsorship of the Basilicata’s regional government, New Yorkers and tourists will be able to enjoy an additional treat this Christmas season. On display in newly-restored St. Patrick’s Cathedral is a crèche by native-son artisan Franco Artese. (The capital of this almost land-locked southern Italian region, Matera, famous for its “Sassi” or cavernous habitations and its rupestrian churches, will be one of Europe’s Capitals of Culture in 2019.) Artese’s crèche, unveiled in person by Pope Benedict XVI, was on display in St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City during Christmas time in 2012 and in Turku, Finland, in 2013. Each year Artese adds new figures. This year they are appropriately a family of immigrants, in honor of the millions of Italians who between the 1880s and 1920s immigrated to the United States in search of a better life.

In 1983, when he was 26 years old, Artese went to the United States for the first time to set up, on behalf of the Italian government, a Nativity scene of 100 square meters in Our Lady of Pompeii Church on Carmine Street in Greenwich Village, Lower Manhattan, the neighborhood once known as “Little Italy.” More than 800,000 people came to see it.

Facebook Comments