The school’s President, Brian Black, tells the story of a school which combines much-needed technical training with Catholic spirituality.

By Brian Black*

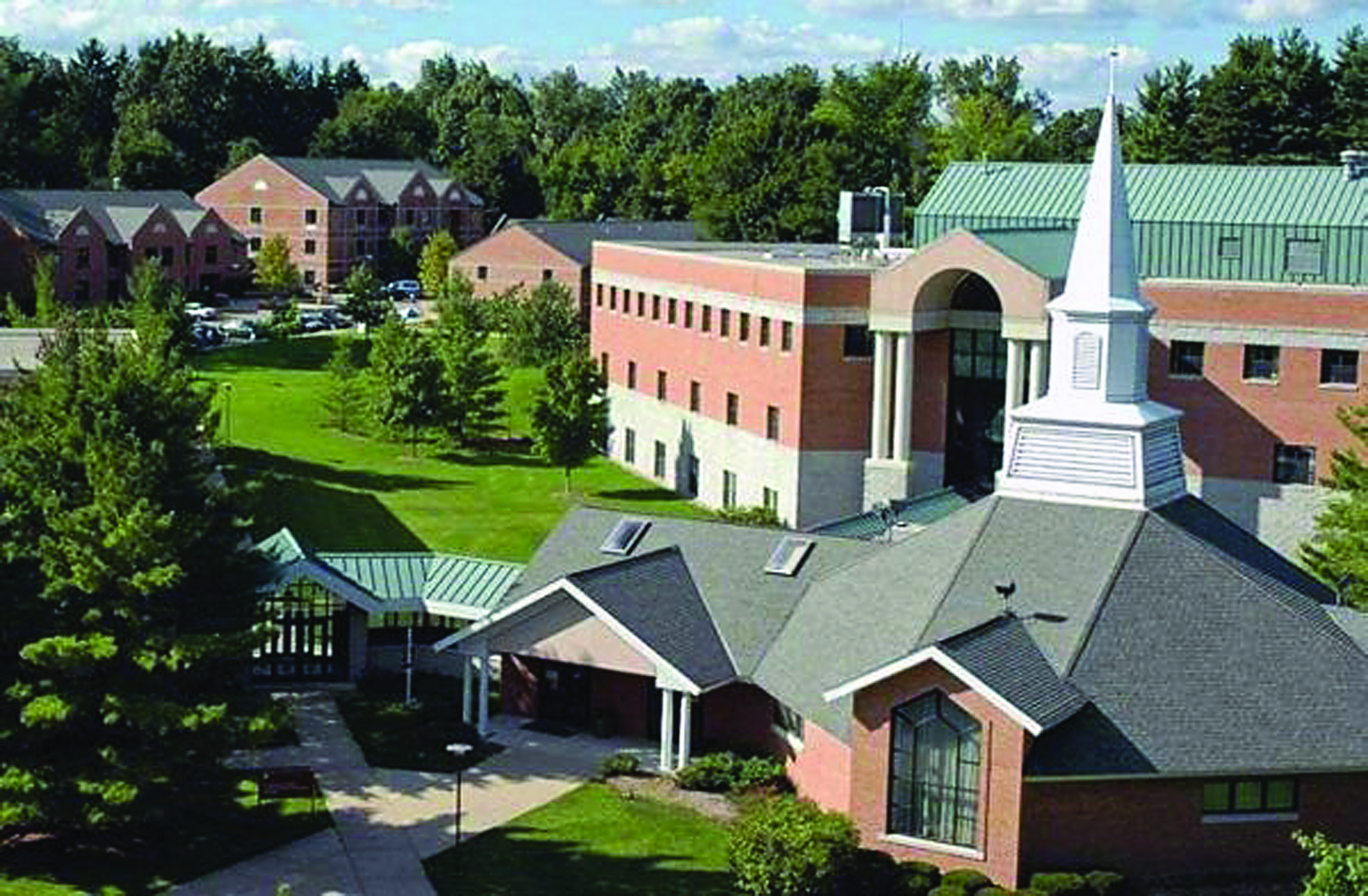

Harmel Academy, hosted on the beautiful campus of Kuyper College in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Harmel students live in dedicated dormitory floors, and receive instruction in dedicated classrooms and labs

Several years ago, a friend and I began an extended conversation built around a simple question: why is it that an aspiring nurse can find a college to form her in both a career and the spiritual life, but an aspiring machinist cannot? Or to put it in other words, why does Catholic higher education blend spiritual formation, intellectual formation, and career preparation for only certain types of careers?

If you are interested in medicine, law, advertising or the sciences, there are plenty of Catholic institutions you can choose from which will, through excellent programming and faithful professors, wed the specifics of those fields to the life of holiness. But what if you were gifted with a mechanical genius? Or what if you were called to a life working as an electrician, a welder, a manufacturing technician, or a plumber? Because such fields require the skilled use of your hands as well as a disciplined use of your mind, are they somehow removed from the call to holiness?

To put it bluntly: why aren’t Catholic schools educating young people in the skilled trades?

The question takes on a new significance when you remember that Our Lord himself spent most of his life on earth working as a skilled craftsman, laboring away in a sweaty workshop and serving his neighbors in what could otherwise have been a life of humble, but fruitful, obscurity. Since Our Lord himself was a working man, it seems obvious that the Church should not only hold the skilled trades in especially high esteem, but that she ought to make it a priority to provide training, spiritual formation and intellectual formation for workers.

However, as far as we could tell, there was no place where such training and formation were offered side-by-side. At best, a young person would have to find work or an apprenticeship, but if he wanted spiritual and intellectual formation to go along with it, he was largely on his own. “Why is no one doing this?” It was a question we could not escape.

We soon realized that the persistence of the question itself was God’s way of asking us to create a new school — in fact, a new type of school — to train skilled tradesmen in craft, intellect and holiness. And finally, earlier this year, Harmel Academy of the Trades was born.

As I write this, Harmel Academy of the Trades is mere days away from welcoming its founding class, a small group of impressive, creative young men who have discerned that the “normal” modes of education simply are not for them.

Some of these men are coming from liberal arts schools. Some of them are coming from Catholic high schools. Some are coming from homeschools.

One is coming from the National Guard.

But all of them have this in common: they could not find a place that could satisfy their desire to be spiritually formed in a faithful Catholic community while at the same time helping them develop their God-given gifts in the skilled trades.

There are many reasons — practical, financial, social, pedagogical — why a school such as Harmel hasn’t existed yet, at least in the form it has taken here in Grand Rapids, Michigan. But never has there been a time when such an enterprise is more needed.

For one thing, the skilled trades in America are themselves in something of a crisis. After spending an entire generation convincing young people that careers in the trades were somehow “less” than a career that required a college degree, the American economy is facing critical shortages in skilled labor. As the previous generation of skilled workers retires, the crisis is growing.

But more importantly, no matter the field or career, there exists an even deeper crisis, a philosophical and spiritual problem: we have forgotten how to work and what work is for.

It may seem odd to say that forgetting what work is for is a philosophical and spiritual problem. But it is so in the same way that misunderstanding human sexuality is a philosophical and spiritual problem.

In recent decades, the Church has helped Catholics meet the problems of sexuality in the modern world, most notably through the Theology of the Body developed and proposed by Pope Saint John Paul II. Confusion about sexuality was rooted in a type of forgetfulness of, or an inability to read, the language of our bodies. John Paul, by reading this language in the light of the Gospel, clarified for our generation, and all to come, the deeper meaning of human sexuality.

Similarly, our forgetfulness about work — what it is, how to do it, why to do it — is rooted in an inability to read the same language of the body, but with a different point of emphasis. The Theology of the Body has given us new insight into the conjugal nature of our human being, and its telos — its end — as divine communion. But there can also be, and I believe should be, a theology of the body for human work — one that will, once examined, help us rediscover work’s telos as divine cooperation.

John Paul himself laid the groundwork for the clarification of human work by reading the language of the body through the Gospel, most notably in his encyclical Laborem Exercens. In a nutshell, John Paul teaches that any recovery of human work — any just system of economics, any program of social responsibility — must be built not simply on an understanding of the science of work and economics. It must, before all things, be built on a recognition of the subjective nature of work.

In other words, the proper focus of any attempt to understand work is not work, per se, but rather the man working. The most essential truth is that when man exercises his intellect and his body in the intentional formation of the material world — in other words, when he works — it is not only, and not even primarily, the material world that is being formed. In working, man forms himself. Or, more accurately, man collaborates with God in his own formation.

With such an important calling, how is it possible that, as Catholic educators, we have neglected to provide a formation in the high and holy calling of human work?

We should not be too hard on ourselves. The reason we have overlooked it is the same reason you overlook anything intensely familiar. Work is so close to our everyday experience, we simply don’t see it.

But the time has come to see it, and to see it in a new and fresh way, because there is a generation of young people who will be called to meet a social question that has become so complicated and so challenging that, unless they are prepared to meet it, they may be crushed by it.

Work is the key to the social question. Just as our namesake, Leon Harmel, was committed to addressing the social challenges of the Industrial Revolution through a focus on the formation of the Catholic family and the Catholic worker, so too is Harmel Academy of the Trades dedicated to helping the Church clarify the challenge and opportunity of work for the coming generation.

Brian Black, President of Harmel Academy of the Trades, with the school logo containing the cross

*Brian Black is president of Harmel Academy of the Trades, a new Catholic residential trade school in Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA. For more information, visit HarmelAcademy.org.

Facebook Comments