Our special Urbi et Orbi section, in which we highlight the spirituality, prayer, customs and practices of our brothers and sisters in the churches of the East, continues...

We begin the penitential season of Lent — the season in which we most profoundly enter into the mysteries of Christ’s redemption of the human race. And it is well to look to the East, the cradle of His Church, for insight and inspiration as we prepare to immerse ourselves in these mysteries.

In Lent, the Eastern-rite Catholic and Orthodox Churches focus intently on awakening in man the awareness of his need for repentance. The daily liturgies, appointed prayers and more strenuous fasting practiced in the Eastern Churches all recall us to this urgent task. So, in this issue, we hope to bring our readers a glimpse of the counsels and practices that abound in Eastern Christianity during this holy season of preparation.

May they serve in some way to help all of us awaken in our spirits the metanoia, as it is called in Greek, the re-orientation, the turning away from our past selfishness and sin, and toward our loving and merciful God. “For this life,” states John Chrysostom, “is in truth wholly devoted to repentance, penthos (grief, mourning) and wailing. This is why it is necessary to repent, not merely for one or two days, but throughout one’s whole life.”

St. John Chrysostom, Patriarch of Constantinople at the beginning of the 5th century, delivered nine homilies on repentance in Antioch of Syria sometime between 386 and 387, emphasizing that repentance was a necessity for both the sinner and the righteous man.

The need for repentance has rich biblical roots, and Chrysostom masterfully wove a plethora of Old and New Testament citations into his teaching. Scripture tells us that repentance is never confined to the Eucharistic context — it becomes a way of life for the believer. Chrysostom preached that the whole experience of a true life in Christ is repentance that culminates in metanoia — the total change and renewal from the heart and mind of sin to “the mind of Christ” (1 Cor. 2:16).

Here he outlines the “paths to repentance.”

Would you like me to list also the paths of repentance?

They are numerous and quite varied, and all lead to heaven.

A first path of repentance is the condemnation of your own sins: Be the first to admit your sins and you will be justified.

For this reason, too, the prophet wrote: I said: I will accuse myself of my sins to the Lord, and you forgave the wickedness of my heart.

Therefore, you too should condemn your own sins; that will be enough reason for the Lord to forgive you, for a man who condemns his own sins is slower to commit them again.

Another and no less valuable one is to put out of our minds the harm done us by our enemies, in order to master our anger, and to forgive our fellow servants’ sins against us. Then our own sins against the Lord will be forgiven us…

Do you want to know of a third path? It consists of prayer that is fervent, careful and comes from the heart.

If you want to hear of a fourth, I will mention almsgiving, whose power is great and far-reaching.

If, moreover, a man lives a modest, humble life, that, no less than the other things I have mentioned, takes sin away. Proof of this is the tax-collector who had no good deeds to mention, but offered his humility instead and was relieved of a heavy burden of sins. (from Hom. De diabolo tentatore 2, 6: PG 49, 263-264).

“True fasting is to be converted in heart and will…” The place of fasting in Orthodox Christian spirituality

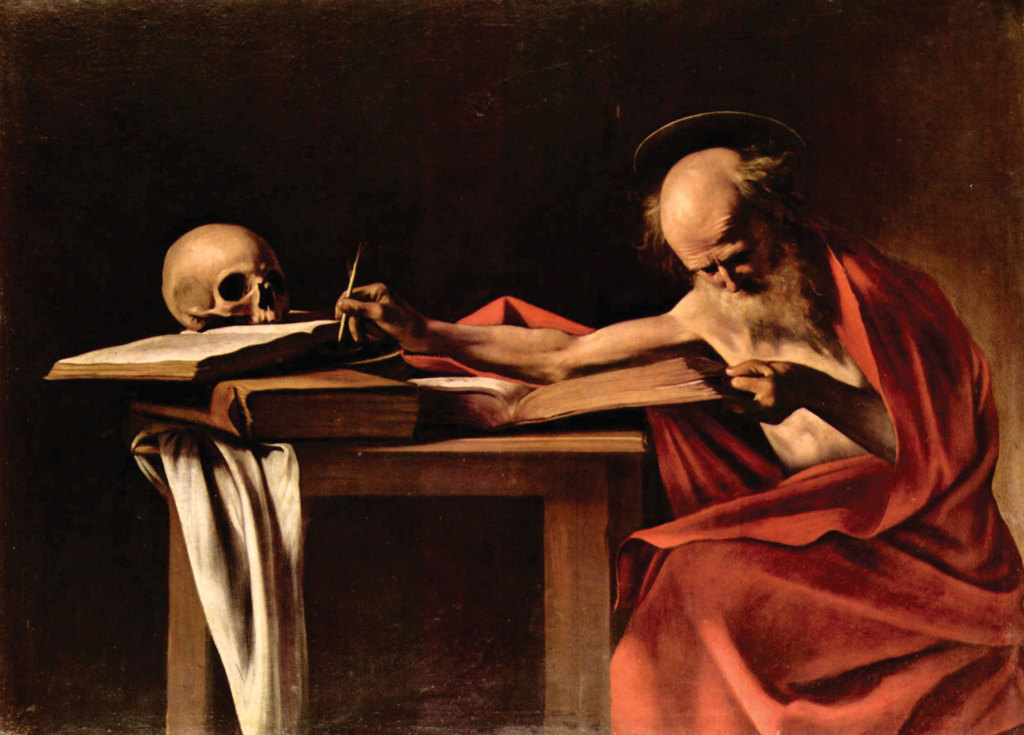

‘St. Jerome writing’, by Caravaggio. TheOld and New Testments were translated into Latin by Jerome, who in the mid-300s was the personal secretary of Pope Damasus; in the late 300s he lived in Betlehem.

The “sense of Resurrection joy…” according to Bishop Kallistos Ware, English Greek Orthodox bishop under the Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople, “is the one and only basis for our Christian life and hope.” Yet, experiencing the fullness of Paschal rejoicing requires an “expectant preparation,” without which the deeper meaning of Easter will be lost.

So it is that present Orthodox usage includes a preparatory penitential period lasting more than nine weeks, lengthier than the Catholic Church’s 40 days of Lent and more rigorous in its fasting prescriptions.

The Orthodox observe a preliminary period of 22 days (including four successive Sundays), followed by 40 days of the “Great Fast” of Lent, and finally, Holy Week. Balancing this period is a corresponding season of 50 days of thanksgiving, from Easter to Pentecost.

Each season has its own liturgical book: the Lenten Triodion and the Pentekostarion for the time of thanksgiving. Bishop Ware describes the Triodion as the “book of the fast.” He says, “Just as the children of Israel ate the ‘bread of affliction’ (Deut. 16:3) in preparation for the Passover, so Christians prepare themselves for the celebration of the New Passover by observing a fast.”

But fasting is much more than an outward, physical abstention from certain food and drink; it has “an inward and unseen purpose… the primary aim of fasting is to make us conscious of our dependence upon God,” says Bishop Ware. “Lenten abstinence gives us the saving self-dissatisfaction of the Publican (Luke 18:10-13). Such is the function of the hunger and the tiredness: to make us ‘poor in spirit,’ aware of our helplessness and of our dependence on God’s aid.”

St. John Climacus wrote the ‘Ladder of Divine Ascent’ whereby each step describe a virtue, and together they describe the progress of a person’s spiritual struggle, which leads to Perfection.

“True fasting,” he continues, “is to be converted in heart and will; it is to return to God, to come home like the Prodigal to our Father’s house. In the words of St. John Chrysostom, it means ‘abstinence not only from food but from sins… The fast,’ he insists, ‘should be kept not by the mouth alone but also by the eye, the ear, the feet, the hands and all the members of the body.’”

Until the 14th century, both Western and Eastern Christians abstained from not only meat, but also from animal products like eggs, butter, milk and cheese, and even fish, oil and wine — requiring significant effort and sacrifice.

Western Christendom gradually relaxed its fasting rules, but the Orthodox, at least in prescription if not always in widespread practice, still keep a strict Lenten “Great Fast,” as well as other minor fasts throughout the liturgical year.

Fasting begins in a small way even before Great Lent, with the faithful abstaining from meat after the final “Meatfare Sunday,” a week prior to the start of Lent, but still able to consume dairy products through the following “Cheesefare Sunday.”

In fact, the liturgical readings of the four Sundays before Great Lent have specific “lessons” which the Church seeks to impress on the faithful as they prepare for the penitential season:

– Sunday of the Tax Collector and Pharisee (from the parable) – the uprooting of arrogance and embrace of humility

– Sunday of the Prodigal Son (from the parable) – repentance and obedience

– Meatfare Sunday (the Final Judgment) – reminder of the need for correcting our faults by prayer, fasting and almsgiving

– Cheesefare Sunday (Adam’s Expulsion from Paradise) – recognition of the condescension of God to our human weakness

Although fasting is considered an integral part of the Christian life — as one source put it, “one cannot be an Orthodox Christian and not fast” — the Orthodox Church’s attitude is one anxious to avoid legalism. The Orthodox faithful are encouraged to observe the rules of fasting, but not under pain of sin, “for the kingdom of God is not food and drink, but righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy Spirit” (Rom. 14:17).

The Bright Sadness

The Orthodox saint John Climacus calls Lent a time of “joy-making mourning” — poetically translated as “bright sadness” — which recalls to us a state of mind and spirit that should permeate our lives: the hymns and texts of the Triodion remind us that we, as sinners, have fallen short, engendering a sense of sorrow.

At the same time, as prayer and fasting induce us to relinquish our self-centeredness, we experience also a certain joy in our hearts; hence, the “bright sadness” of Lent is meant, in fact, to be a liberating experience.

Fasting on Mondays

“Leaders of the heavenly armies, although we are unworthy, we always beseech you to fortify us by your prayers and to shelter us beneath the wings of your sublime glory. Watch over us who bow to you and cry out fervently: Deliver us from danger. For you are the commanders of the powers on high.” – Common Troparion for Mondays

Each Monday, the Orthodox remember the angels in their liturgy, and many monasteries and even individuals fast on Mondays in honor of these “attending spirits” who serve God and His will. “It is a beautiful thing for every one of us to start on every Monday morning of each week like an Angel on a mission of goodwill…who brings messages of love and salvation to his house, to his neighborhood and to the greater world around him.”

“Through the intercessions of the Bodiless Powers, Lord, save us.” —Metropolitan Irenaius of Kisamou and Selinou, Crete.

“O Lord and Master of my life, take from me the spirit of sloth, faintheartedness, lust of power, and idle talk. But give rather the spirit of chastity, humility, patience and love to your servant. Yes, O Lord and King, grant me to see my own sin and not to judge my brother, for You are blessed from all ages to all ages. Amen.”

—The Prayer of Saint Ephraim the Syrian, traditionally said many times throughout each day during Great Lent, in addition to daily prayers.

“Adam, God’s first-formed man, transgressed: could He[God] not at once have brought death upon him? But see what the Lord does, in His great love towards man. He casts him out from Paradise, for because of sin he was unworthy to live there; but He puts him to dwell over against Paradise: that seeing whence he had fallen, and from what and into what a state he was brought down, he might afterwards be saved by repentance.”

—St. Cyril of Jerusalem

Facebook Comments