The Council’s time in history has passed

By Anthony Esolen

The Council of Trent (1588) by Pasquale Cati Da Iesi

Thomas Aquinas

(between Aristotle and Plato) Defeats Heresy, by

Benozzo Gozzoli

John Henry Newman, a convert from Anglicanism, elevated to the cardinalate in 1879 by Leo XIII, proclaimed a saint in 2019 by Pope Francis

The doctrine of infallibility is, to my understanding, modest and protective: it declares that the Church will never, in matters of faith and morals, preach what is false. It does not declare that the Church will be free of folly or wickedness.

Cardinal Reginald Pole, whose native England had severed herself from Rome, said at the Council of Trent that the divisions in the Church were God’s punishment for the corruption of her princes.(1)

What the sins were for which the aftermath of Vatican II was the punishment, I cannot tell, unless they were the simmering acts of treachery and apostasy that characterized some of the principals at the Council, and many priests, religious, and laymen around the world in the years that followed.

About the Council documents I will have little to say here. The choice for a “hermeneutic of continuity,” which Archbishop Vigano suggests has failed, seems to me to be an absolute necessity by any conceivable understanding of what the Church is, what truth is, and what genuine “development of doctrine” is, as set forth most precisely by St. John Henry Newman.

A hermeneutic of rupture — the notion that at Vatican II the Holy Spirit cut the Church clean from her past, to establish a new thing — is a flat contradiction of the promises of Christ. It denies the Church’s essence as a body maintaining her identity through all the chances and changes of the world, and, in her moral and spiritual growth, always remaining the same Church, coming to deeper understanding of truths already held. Marriage does not develop by divorce. If the documents of Vatican II can be brought into harmony with what the Church has always taught, then they must be, regardless of the intentions of the attending prelates and theologians.

Here we come to a crux, one of three that I will look at here. The first involves the distinction between the Church and a political body.

Thomas Aquinas says that judges and magistrates who execute the law must be guided by the mind of the lawgiver, rather than construing the law to negate what the lawgiver intended to do. That is because, in any political system, each officer has his proper function which he should not overstep. It is also because law is general and universal, not specific and particular; no lawgiver can anticipate every eventuality. Therefore we require the astute obedience of the judge or magistrate, who does not take the law into his own hands, but, in deference to the mind of the lawgiver, applies the law justly to the matter before him.

In a severely limited sense, we may say something similar about how responsible Churchmen should have implemented certain directives laid out in the Council documents: for example, the directive in Sacrosanctum concilium to bring to the faithful the Church’s immense musical wealth, and to confirm the pipe organ as the instrument most fit for the worship of God. Such identity-conserving directives were ignored. Instead, people appealed to the “spirit of Vatican II” — what I have called “the Ghost of Vatican Past” — to justify innovations that were often at odds with what the documents themselves say.

But the spirit of Vatican II is a fiction. Not even in the political sphere may a judge appeal to the spirit of a senate debate; he has the law before him, and the law, not excitations in the senate chamber or conversations in a cloak room, not what this or that lawgiver wanted and did not get, not hearsay, not fervid reports from priests writing under a pseudonym, not some supposed farther advance of the law, must express for him what the lawgivers intended.

But the lawgiver here is the Holy Spirit and not men, and that makes all the difference in the world.

We are not permitted to guess at the mind of the Holy Spirit, as if He were chief among the political actors at the Council. The Council cannot claim to speak for the Holy Spirit, simpliciter. Again, we believe that the Holy Spirit will guard the Church against preaching error.

We do not believe that the Holy Spirit speaks positively through every Pope or Council Father as through a pasteboard mask. Indeed, those revolutionaries among the Fathers at Vatican II can have believed no such thing, or else there never would have been a Vatican II to begin with; Vatican I would have had to suffice.

No, when we interpret any papal pronouncement or any Council document proclaiming a matter of faith or morals, we must assume that the Holy Spirit cannot change, cannot contradict himself.

The words then are our concern. Unlike the words of a human lawgiver, they deal with the eternal.

The first crux implies a second. The great movers of Vatican II regarded the Council as a new foundation for the Church. We may call this “the Modernist Gambit.” You scoff at the past as benighted, outworn, even stupid and wicked, but certainly determined by time and place, and therefore to be discarded now that we have a new time and place.

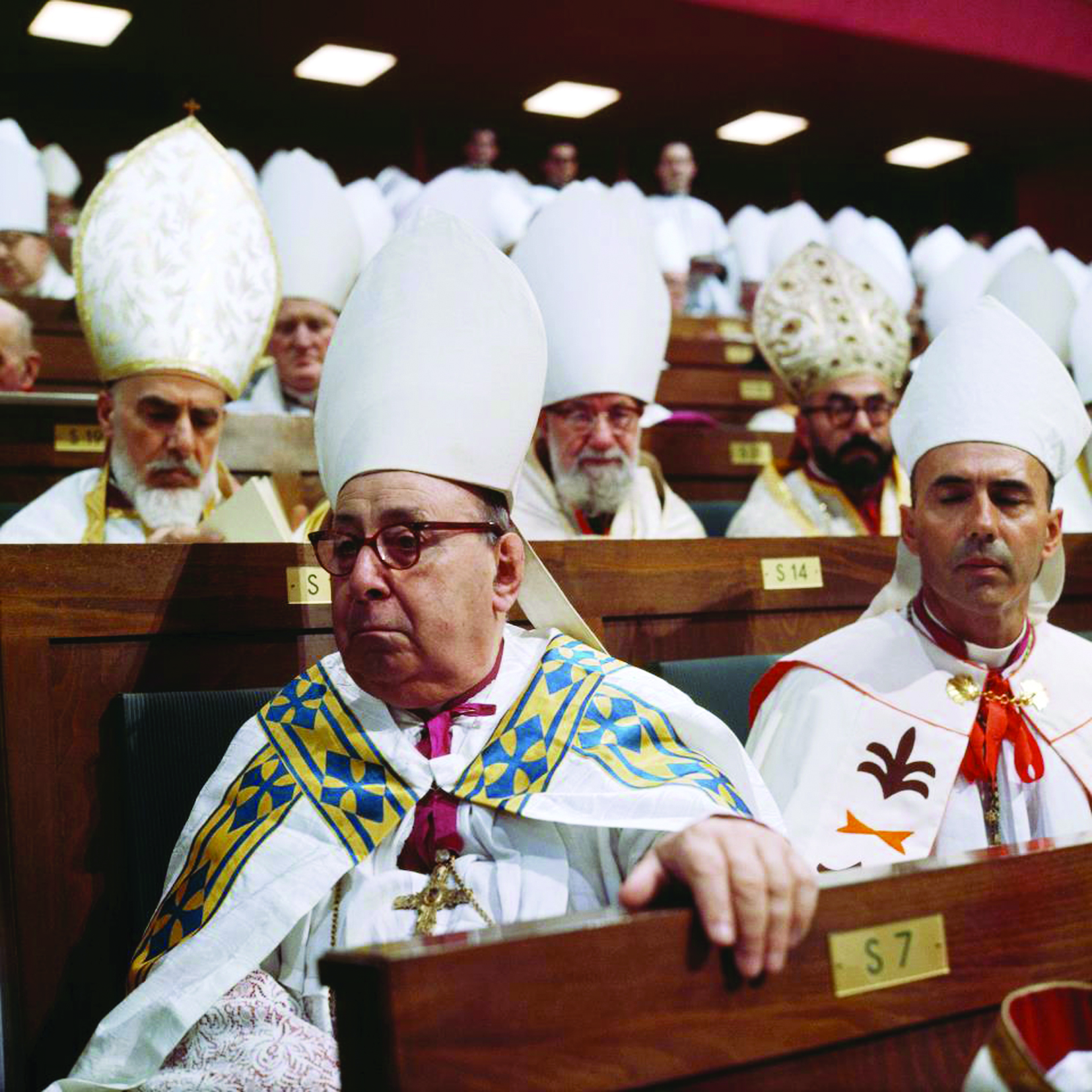

The Council Fathers during a session of Vatican Council II

That is nonsense, even in secular arts and letters; who says that Bach is benighted or that Shakespeare is outworn?

But almost in the same breath, the Modernist, having cut himself adrift from the ages, declares that he alone is not determined by time and place; he or the direction he travels in is absolute, inevitable, unquestionable. The Modernist sacrifices man, says Gabriel Marcel, to the Minotaur that is “history.” We are floating on a raft downriver to a 1,000-foot waterfall, but if that is where the river is going, we should flow with it too, for the river is History, or what we fancy to be History, and that fiction has become our god.

That brings me to my third and final crux. The Council Fathers wanted to address the Church to the modern world. It was a pastoral Council, not a dogmatic Council — so we have heard.

Here I note that when you seek heaven first, you will get earth into the bargain; that is what Jesus promises. When you seek earth first, you lose both.

The innovators at the Council thought in modern political terms, and therefore, unless they were devils intending to destroy, they were inept even at the task they had set for themselves.

Pastorally, the Council was a calamitous failure: vocations to the priesthood and religious life dried up; schools shut down; colleges shut down or apostatized; Catholic arts and letters, that had given the world several Nobel laureates in literature, collapsed; great music was abandoned for the stupid and treacly; and Catholics capitulated to the Lonely Revolution around them, that abandonment of the Christian sexual ethic that had shed its sweet light upon the lives of ordinary Christians, and had trained them up in virtue and sanctity. The modern world was already a dead thing, deadening all it touched.

Modernism subtracts, minimalizes, obliterates. Should the Church bind herself to a corpse? If ever there was a time to be buried in forgetfulness, it was that late modern age, so rich in things and poor in soul.

We say, with embarrassment, that the Spanish Inquisition was not as bad as people think, and that it should be understood in the context of its time and culture.

So also Vatican II: it should be understood in the context of the time — and the time has passed.

It did not affirm error. Its implementers did little good and much mischief. Enough already.

The sooner we forget it, the sooner we bid it leave the throne it never deserved, the sooner we cast off its dated liturgical innovations — as dated as Godspell and the Singing Nun — the better.

(1) Cardinal Reginald Pole lived from 1500 to 1558 and was the last Catholic archbishop of Canterbury under Queen Mary’s brief Catholic restoration, from July 1553 to her death in November of 1558. Mary was the only child of King Henry VIII by his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, to survive to adulthood. Her attempt to restore to the Catholic Church the property confiscated in the previous two reigns was largely thwarted by Parliament, but during her five-year reign, Mary had over 280 religious dissenters burned at the stake, which led to her denunciation as “Bloody Mary” by her Protestant opponents. Cardinal Pole died about 12 hours after Queen Mary herself on November 17, 1558.

About the author: Professor Esolen graduated summa cum laude from Princeton University in 1981. He pursued graduate work at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he earned his M.A. in 1981 and a Ph.D. in Renaissance literature in 1987. Esolen’s dissertation, “A Rhetoric of Spenserian Irony,” was directed by Prof. S. K. Heninger. Esolen taught at Furman University and Providence College before transferring to the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in 2017 and, in 2019, to Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts in southern New Hamsphire, USA, where he is Writer-in-Residence. Esolen has translated into English Dante’s Divine Comedy, Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things, and Torquato Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered.

About the author: Professor Esolen graduated summa cum laude from Princeton University in 1981. He pursued graduate work at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he earned his M.A. in 1981 and a Ph.D. in Renaissance literature in 1987. Esolen’s dissertation, “A Rhetoric of Spenserian Irony,” was directed by Prof. S. K. Heninger. Esolen taught at Furman University and Providence College before transferring to the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in 2017 and, in 2019, to Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts in southern New Hamsphire, USA, where he is Writer-in-Residence. Esolen has translated into English Dante’s Divine Comedy, Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things, and Torquato Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered.

Facebook Comments