“If Cardinal Schönborn will rethink his decision, and will consider all these aspects and consequences of his decision, I sincerely hope and pray that he will take it back.”

—Prof. Joseph Seifert

The case of the openly homosexual Austrian Catholic whose election as president of his parish council was first overturned by his parish priest, then reinstated by Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, archbishop of Vienna, is sparking global debate.

One of the most complete and persuasive summaries of these events and their significance comes from Professor Joseph Seifert, a leading Catholic philosopher from Austria who is a long-time friend of Schönborn (as I am), but who opposes the cardinal’s decision in this case, and is asking him to reverse his decision (see here).

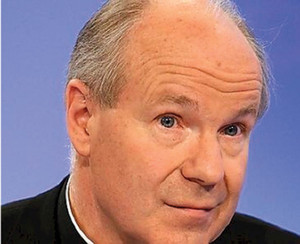

Cardinal Christoph Schönborn of Vienna, Austria

Here are the facts as Seifert lays them out: “Christoph Cardinal von Schönborn, archbishop of Vienna, Austria, and president of the Austrian Bishops’ Conference, has recently overruled the decision of a Polish pastor in a small village in Lower Austria. The pastor, Gerhard Swierzek, had decided against the election to the parish council of a man who openly practices a homosexual lifestyle and has even had his homo-union and quasi-marriage registered publicly. The cardinal, who had initially indicated support for Swierzek’s decision, invited the young man (26), Florian

Stangl, and his partner to his palace for lunch. And then, after this surprising invitation, he announced publicly and still more surprisingly his decision to overrule the pastor and allow the election of Stangl to stand. The cardinal commented further that he was impressed by the faith and Christian attitude of the two men, and that he understood why Mr. Stangl had been elected by the highest margin of votes in his favor. (The cardinal did not meet with the pastor, who had sought a conversation with him.) The decision has been praised and defended by many, and criticized by many others, including other bishops and cardinals, who find it incomprehensible.”

Among the defenders of the cardinal’s decision are not only homosexual lobbies or the large group of Austrian and other priests who formed an association that publicly dissents from Church teachings and discipline, but also the former Italian minister of European politics, and former pro-rector of the International Academy of Philosophy in the Principality of Liechtenstein, Professor Rocco Buttiglione. Buttiglione defends the cardinal’s decision “on the grounds that we are all sinners and that to live in sin does not automatically destroy Catholic faith or exclude practicing homosexuals and other sinners from a fruitful collaboration in an ecclesiastic political body such as a parish council,” Seifert notes.

Seifert argues that “in this instance my admired friend (Buttiglione) is wrong.” He adds: “Even the best arguments in favor of the cardinal’s decision, I believe, clearly fail to take into account important distinctions, in the light of which, in my opinion, the cardinal’s decision should be taken back, or reversed by Rome.”

Seifert argues that “being a sinner is not the same as living in a state of serious sin.” He says: “Whatever the subjective conscience of Mr. Stangl tells him, and whatever God’s judgment on his acting might be (which we do not know and may not presume to know), the state in which he openly lives is, according to the Church, an objective state of grave sin — a state in which we do not all live.”

Further, “the homosexual life of Stangl is evidently not recognized by him to be sinful,” Seifert writes, but “rather, he insists on its being morally quite admissible.” Seifert argues that, in this case, “the action of the cardinal inevitably produces the illusion of Church approval of homosexual relations and sets up a morally bad example.”

Moreover, “there is an important difference between a sin committed privately and hidden from the public, and a sin committed openly,” Seifert contends. “A priest who sins in secret, however deeply sad this is, at least expresses an element of shame for his actions and may just want to avoid a bad public example — without any hypocritical intention to lie and deceive the faithful. In contrast, a pastoral council member who openly professes his homosexual relationship (in whose sinfulness he does not believe) may be displaying shamelessness rather than honesty.”

Seifert concludes his argument this way: “If Cardinal Schönborn… will rethink his decision, over which I feel doubly deep sadness as a Catholic and as a friend, and will consider all these aspects and consequences of his decision, I sincerely hope and pray that he will take it back, in obedience to the truth and to the Church and notwithstanding any embarrassment such a change of decision may involve. For even if such a change of decision will outrage some, and provoke criticisms or derision by others, an honest act of admitting a mistake, which, if what I have expounded is true, this decision is, is never a good cause of feelings of shame, but deserves admiration and gratitude. I hope that neither His Eminence nor my friend Buttiglione will take amiss what the commitment to truth we share has required me to say.”

When a cardinal overrules a parish priest and acts in a way that appears to contradict the constant teaching of the Church, what does that say to the ordinary faithful, the “little ones” who Benedict has repeatedly said are his special concern?

We share Seifert’s view. Schönborn should reverse this decision, or Rome should overturn it.

Facebook Comments