“Academic Freedom” and the Tyranny of the Modern College Campus

By Michael F. McLean, Ph.D., President of Thomas Aquinas College*

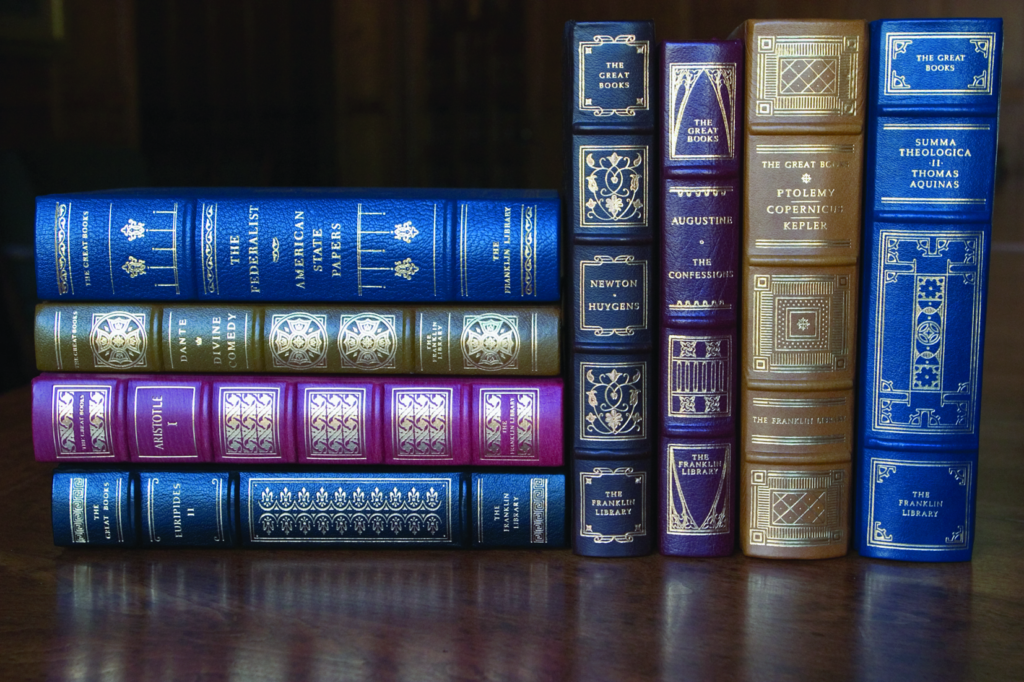

Some of the titles read in the “Great Books” curriculum at the college.

Fr. Theodore Hesburgh, president of Notre Dame University and signatory to the “Land O’Lakes Statement” in 1967

Last fall, one of the preeminent Catholic universities in the United States terminated a professor for an unspecified offense. We know not all the details, but the incident seemingly began when the white lecturer confused the names of two black students. He then compounded his wrongdoing by emailing all of his students to argue that — mounting allegations to the contrary — his error did not make him a racist. To bolster his case, his email listed his many contributions to the cause of racial justice.

Such defensiveness, according to an aggrieved student quoted in the college newspaper, hinted at a “white savior complex” on this instructor’s part — a thoughtcrime that, no matter how thinly evidenced, could not go unpunished. The university promptly relieved the professor of his duties, his salary, his benefits, and his reputation.

As a teacher who has, on occasion, called students by the wrong names, it is difficult to fathom how such a simple error could lead to such an uncharitable and merciless judgment. Yet stories like this one are now alarmingly commonplace. Throughout much of academia, expressing the wrong opinion — or even the mere suspicion of holding the wrong opinion — is sufficient grounds for censure, de-platforming, and ostracism.

In the parlance of the moment, we chalk up such abuses to “wokeism,” or its precursor, “political correctness.” But to get to the heart of the rampant intolerance that characterizes life on most college campuses today, we need to go back to the late 1960s, when this phenomenon first took root. Back then it was called, ironically, “academic freedom.”

The Modern University

When various leaders from the country’s premier Catholic universities gathered in Land O’Lakes, Wisconsin, in 1967, they authored a document titled “The Idea of the Catholic University,” now known more commonly as the Land O’Lakes Statement. “The Catholic University today must be a university in the full modern sense of the word,” the document asserted. “Institutional autonomy and academic freedom are essential conditions of life and growth and indeed of survival for Catholic universities as for all universities.”

More than just platitudes, these words were, in effect, a declaration of independence.

Traditionally, the Catholic university had conducted its instruction and research in fidelity to the teachings of the Church — the magisterium set the moral and intellectual boundaries that guided students and faculty along the path to truth.

But no longer. “The intellectual campus of a Catholic university has no boundaries,” the authors proclaimed. “The Catholic university must have a true autonomy and academic freedom in the face of authority of whatever kind, lay or clerical, external to the academic community itself.”

Note those words, “authority of whatever kind,” which encompass not only religious communities, the local bishop, and the magisterium, but God Himself. “The student will be able to develop his own capabilities and to fulfill himself by using the intellectual resources presented to him,” the statement continued. The student alone — well, the student, the professor, and the university administration, anyway — would define what is true. Whether wittingly or not, in seeking to emulate the standards of their secular counterparts, the leaders of the nation’s top Catholic universities were casting their lot with a revolution that was speedily making its way through the academy.

Dr. McLean, president of Thomas Aquinas College

Untether higher education from Christianity and its intellectual tradition, the revolution’s proponents promised, and students would achieve new heights in learning, “free” from the outdated conventions that shackled social progress.

It didn’t work out that way.

The revolutionaries got everything they wanted and more — purging the Great Books from the classroom, abandoning integrated curricula for a multiplicity of majors, dismantling any rules of residence that may have encouraged personal virtue. On Catholic campuses, “autonomy” from the Church was pressed to its limits. Crucifixes came down from classroom walls, while scholars and speakers who brazenly rejected Church teaching were celebrated and tenured.

But the revolutionaries never achieved their envisioned utopia. Nearly 60 years later, colleges are not the bastions of free inquiry that the revolutionaries promised. According to one survey, 62 percent of today’s students find that the intellectual climate on their campuses silences voices that dare to challenge conventional opinion. Another recent poll found that 70 percent of college students favor turning in professors who express an “offensive” belief.

Dueling Statements

Eucharistic adoration in the chapel on the California campus.

Just two years after the Land O’Lakes signatories declared that they no longer needed, nor would any longer accept, the Church’s authority or guidance, another group of Catholic educators put the finishing touches on a wholly different vision of Catholic higher education. They were the founders of Thomas Aquinas College, the institution which I am honored to serve as president. Their 1969 statement, A Proposal for the Fulfillment of Catholic Liberal Education (aka “The Blue Book) is mustreading for anyone who wants to understand how the current crisis in Catholic higher education came to be — and how to overcome it (thomasaquinas.edu/bluebook).

The Blue Book’s authors recognized that schools with no fixed commitment to truth would quickly devolve into what Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI would later characterize as “dictatorships of relativism.” On any campus, they explained, “concrete and particular decisions must be made, about the curriculum, student life, hiring and firing, promotion and so forth.” If these decisions are not governed by revealed truth, they will instead be determined by the whims and dictates of bureaucrats and ideologues. “It would seem that the government of any institution by rules which prescind (or pretend to prescind) from all differences of belief, or which negate in principle the possibility of governing by the truth, must of necessity be tyrannical,” the Blue Book observes, “leaving an infinite latitude in practice to the men who actually make the decisions, who thus rule by their own absolute discretion.”

This is where most of academia finds itself today, a world that the founders of Thomas Aquinas College anticipated 50 years ago, when they set out to create an island of reason in higher education’s quickly expanding ocean of madness. “Divine Revelation … frees the faithful Christian from those specious and yet absurd notions of freedom which, because they are false and subvert the life of reason, deceitfully enslave all who believe in them,” they wrote. “It teaches that self-rule is not the same as independence, but rather that the assertion of complete independence destroys the capacity for self-rule.”

Against all odds, in 1971 these men launched Thomas Aquinas College, offering a single, integrated curriculum rooted in the Great Books and the Catholic intellectual tradition. The school would strive to live out its motto, coined by St. Anselm, of “faith seeking understanding.” And in the succeeding half-century, as other institutions have continually struggled to reinvent themselves by flitting from one academic fad to the next — modernism to postmodernism, subjectivism to scientism, deconstructionism to critical theory — Thomas Aquinas College has remained committed to its founding vision.

For more than 50 years, the College’s students have grappled with the most important questions ever asked, questions about mathematics, language, the good life, nature, nature’s creator, and our place in His creation. In this intellectual climate, which values real academic freedom — where all sincere inquiry is regarded as an avenue to Truth Himself — students of all backgrounds ask the difficult questions and work their way to transformational answers. Rather than being “woke” to the ideological imperative of the moment, these students’ minds have been awakened to eternal truths; their hearts to divine justice and mercy, not mob rule and cancel culture.

It is impossible to miss the workings of Providence in the humble efforts of Thomas Aquinas College over these last 50 years, first on its California campus and now on its Massachusetts campus as well. Yet nowhere were those workings more evident than when the College’s founders resisted the siren song of “academic freedom,” instead offering future generations of students the genuine freedom that comes only from finding and knowing the Truth.

*Dr. McLean is president of Thomas Aquinas College, which has campuses in California and Massachusetts.

Facebook Comments