John Paul II has gone down in history as the pope who disciplined the liberation theologians of Latin America. You played a key role in this event. Could you please tell us more about it?

Professor Rocco Buttiglione: We have to start from the very first days of John Paul II’s pontificate. Before going to Poland the Pope had been to Latin America. Paul VI had promised to attend the Third Latin American Bishops’ Conference in Puebla, and John Paul II kept this promise. The Third Bishops’ Conference was very important because “rebellious” sociology had developed dramatically in Latin America; this sociology regarded the underdevelopment of the continent as a consequence of the capitalist market. At the time the catchword was Mao’s sentence: “Lift yourselves up by your own bootstraps”; underdeveloped countries were exhorted to find a way out of the capitalist market and build up a socialist economy. Liberation theology developed in the wake of this sociology. It all started with Gustavo Gutierrez’ book Liberation Theology, published in 1968. This book was considered to be the result of Vatican Council II and of the Latin American Bishops’ Conference of Medellin.

What is the message of liberation theology?

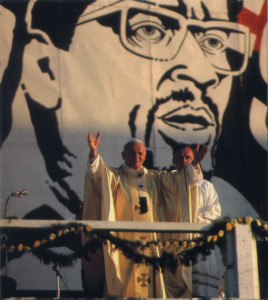

In 1983, Blessed Pope John Paul II made a pastoral visit to Nicaragua. In the photo the Pope presides over a Mass in Managua, Nicaragua. Behind the pontiff is a banner with César Augusto Sandino, national hero in Nicaragua.

It considers the Christian message, not in the abstract, but relates it to the daily life and suffering of the Latin American pauper, to his hopes and journey to liberation. Theology is about eternal life, but Christ’s message is also an exhortation to solidarity, hence a stimulus to transform this world into a place worth living. There is also a third assumption: Marxism is the starting point of liberation, as conceived in the history of Latin America. It makes it possible for us to understand the world from the point of view of the destitute. So, I dare say that liberation theology rests on these three pillars.

There isn’t only one liberation theology, is there?

There isn’t, in fact. There is also a liberation theology which rests on the first two pillars, but not on the third. John Paul II went to Puebla and said two things: first, the Christian message is about liberation; second, this message, far from being abstract, comes to life in the history of a people. This vision came naturally to John Paul II, originating from his conviction that the history of Poland was a journey to liberation in which the Christian faith came to life in the history of the Polish people.

But John Paul II knew from the experience of Poland that Marxism cannot be an instrument of liberation.

That’s true. The third pillar proposed by Karol Wojtyła is in fact the culture of the poor of Latin America. These people are not Marx’ proletariat, but people deeply shaped by evangelization, which has given them dignity and a sense of life (of birth, work and death). And these people conduct their struggle for liberation — they face a situation of long established injustice — in the light of the Christian message, with a Christian attitude. According to John Paul II, liberation theology was to draw upon the tradition of the great evangelizers of Latin America (Bartolomeo de las Casas, Father Motolina, St. Toribio of Mongrovejo, the Jesuits who set up the reductions, i.e., settlements for indigenous people), whose history is the history of the conquest, but also of the evangelization of the continent (it cannot be simply seen as a conquest). So, there is a need for liberation theology, but a theology centered on Christ the Redeemer, who became incarnate in the history of Latin America. We need a struggle for liberation, but a struggle respectful of every human being, which rejects the use of violence, hence incompatible with guerrilla warfare. We must not forget that the one hundred centers of guerrilla warfare advocated by Che Guevara triggered off a great number of coups d’etat by the semi-fascist right all over Latin America. From the 1964 putsch in Brazil to the 1973 putsch in Chile, practically the entire continent fell from the hands of weak democratic governments into those of national security regimes. Guerrilla warfare was responsible for the fall of weak democracies in Latin America.

John Paul II announced another liberation theology. After the Puebla Bishops’ Conference he began a relentless struggle against liberation theology and part of the Latin American episcopate saw the refusal of Marxist-oriented liberation theology as a statement of the necessity for a return to order. Also, there were strong calls for liberation theology to be condemned.

Fr. Gustavo Gutierrez.

It was in this context that the instruction Libertatis nuntius (Instruction on Christian Freedom and Liberation: On Certain Aspects of Liberation Theology) was drawn up by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 1983. It was inspired by John Paul II and prepared by the prefect of the Congregation, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger.

The first instruction on liberation theology was written to meet the demand for elucidation of some doctrinal points. It was intended to clarify some theological theses from which current liberation theology departs, and is centered on the condemnation of Marxism. Marxism cannot be regarded as an instrument of sociological analysis, being a wrong vision of the human person and a biased scientific method.

Why was a second instruction drawn up a few years later?

The first instruction was seen as a total condemnation of liberation theology. But this theology had inspired a widespread social movement, tens of thousands of base communities, lots of charitable activities conducted by the Church, activities in favor of the victims of persecution, and pastoral solidarity. All this seemed to have been condemned, so the Latin American Church was at a loss for a moment.

I played a minor role in the cultural battle of those years with a group of friends: Father Francesco Ricci, Guzman Carriquiry, Alberto Methol, Lucio Gera and Pedro Morandé. We dealt with positive liberation theology under the coordination of Alberto Methol, who had been the head of the CELAM (Latin American Episcopal Council) expert committee. In this context we founded a magazine in Montevideo called Nexo. A Jesuit priest, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, at the time rector of San Miguel Seminary after he had been the provincial of the Society of Jesus for three years, was close to the position of our magazine.

A guerrilla-priest distributes Communion in a village in Central America.

Did you inform John Paul II about the results of your work?

Yes, the Pope invited me to talk about this issue on my return from Latin America. I told him that liberation theology was an umbrella term covering a great number of items: there was a version of liberation theology in Nicaragua (a revolution rather than a liberation theology) in which the figure of Christ had dissolved; this theology was centered, not on God setting his people free, but on the people setting themselves free. This version of liberation theology was to be condemned. On the other hand, there was a liberation theology in Argentina, which was in conformity with the message of the Gospel (let us remember that there was a big non-Marxist Christian labor movement in Argentina): this theology was to be supported and encouraged. Halfway between Nicaragua and Argentina stood Brazil and Gustavo Gutiérrez, whose position was ambiguous.

I remember a curious event: once John Paul II and I were discussing Father Gutiérrez’ liberation theology; at a certain point the Pope asked me: “But … is he (Father Gutiérrez) a believer? Does he celebrate Mass, hear confessions, pray to the Blessed Virgin?” I told him he did, then he replied decidedly: “Things being so, we cannot condemn him! We must talk to him.” All this encouraged the Pope to urge Cardinal Ratzinger to write the second instruction, which made many points clear.

What does the second instruction say in practice?

Blessed Pope John Paul II visited Father Jerzy Popiełuszko’s tomb in Warsaw, Poland, in 1979.

It says that there is a good liberation theology, a bad one (entirely Marxist) and an ambiguous one which has positive aspects, but which needs to be amended (Gutiérrez). I remember that when John Paul II went to Lima, he paid a visit to the last descendant of the Inca as a tribute to these Indian people. That day there were lots of journalists outside Gutiérrez’ house who invited him to say something against the Pope. On the contrary he came out and said: “Today is a feast for my people. Let me go and celebrate with them. There will be another occasion to discuss other questions.” After that Gutiérrez provided all the explanations he had been asked for. He once said: “My theology is perfect. What you criticize about it does not come from our culture; it is all I learnt from you at the universities of Louvain and Munich.” In his later books, especially in the one entitled We Drink From Our Own Wells: The Spiritual Journey of a People, he expresses a radical idea of Latin American theology, rejecting Marxism as a European superimposition. Then he entered the Dominican Order, and now I think that his theology is perfectly in line with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

How did the collapse of the Communist Bloc affect liberation theology?

Long before the collapse of the Soviet Bloc, the events in Poland and the creation of the independent trade union Solidarity made a dramatic impact in Latin America. We tried to connect Solidarity with Latin America. There was great enthusiasm about a non-Marxist Christian labor movement championing the cause of liberation. This hope did not materialize completely, not even in Poland, but it provided a great stimulus.

If Latin America was set free from dictatorships, it was not through guerrilla warfare: the revolutionary left was defeated along with the semi-fascist right. Dictatorships were defeated by a big human rights movement claiming respect for the human person. It was this movement that brought about the fall of the military juntas in Argentina, Chile and Brazil. The years of John Paul II’s pontificate, 1979 to 1989, saw the collapse of the Soviet Bloc along with that of dictatorships in Latin America and elsewhere.

What is left of liberation theology at present?

Little is left of Marxist liberation theology. Unfortunately, after the defeat of communism some rebellious theologians moved from Marxism to the apology of radical society (e.g. by joining the no-global movement). Nevertheless a good liberation theology has remained, the one indicated by John Paul II.

A demonstration of Solidarnosc, a Polish trade union federation. Its opposition to the government led to semi-free elections in the country in 1989.

Do you think that Pope Francis would like to be defined as a liberation theologian?

I don’t know. However, liberation theology originating from sharing the destiny of the poor was part of his vocation. The Christian faith is one, but different in each country. There is only one truth, but there many ways leading to it: among these there is the Latin American way as well as the Polish way. All of these make up the Catholic Church.

So, the claim that the election of Cardinal Bergoglio as Pope is a revenge of liberation theology on John Paul II is ungrounded.

Definitely. Those who say so have not realized what happened, not only in Latin America, but also in Europe and Poland. John Paul II was not “against,” but “in favor,” in favor of Christ. Obviously he had to condemn the violations of human freedom, but his aim was to affirm the truth, not to destroy the adversary. He was against class struggle, but supported the struggle for the truth, which relies on the adversary’s moral conscience. I remember once I told him that communists have no moral conscience, but the Pope replied that we are all in the hands of God and that we must always rely on their conversion. In one of his messages he said that violence needs falsehood, whereas the struggle for justice needs truth. That is why Solidarity won without the use of violence, even though Father Jerzy Popiełuszko and many others had to shed their blood.

Facebook Comments