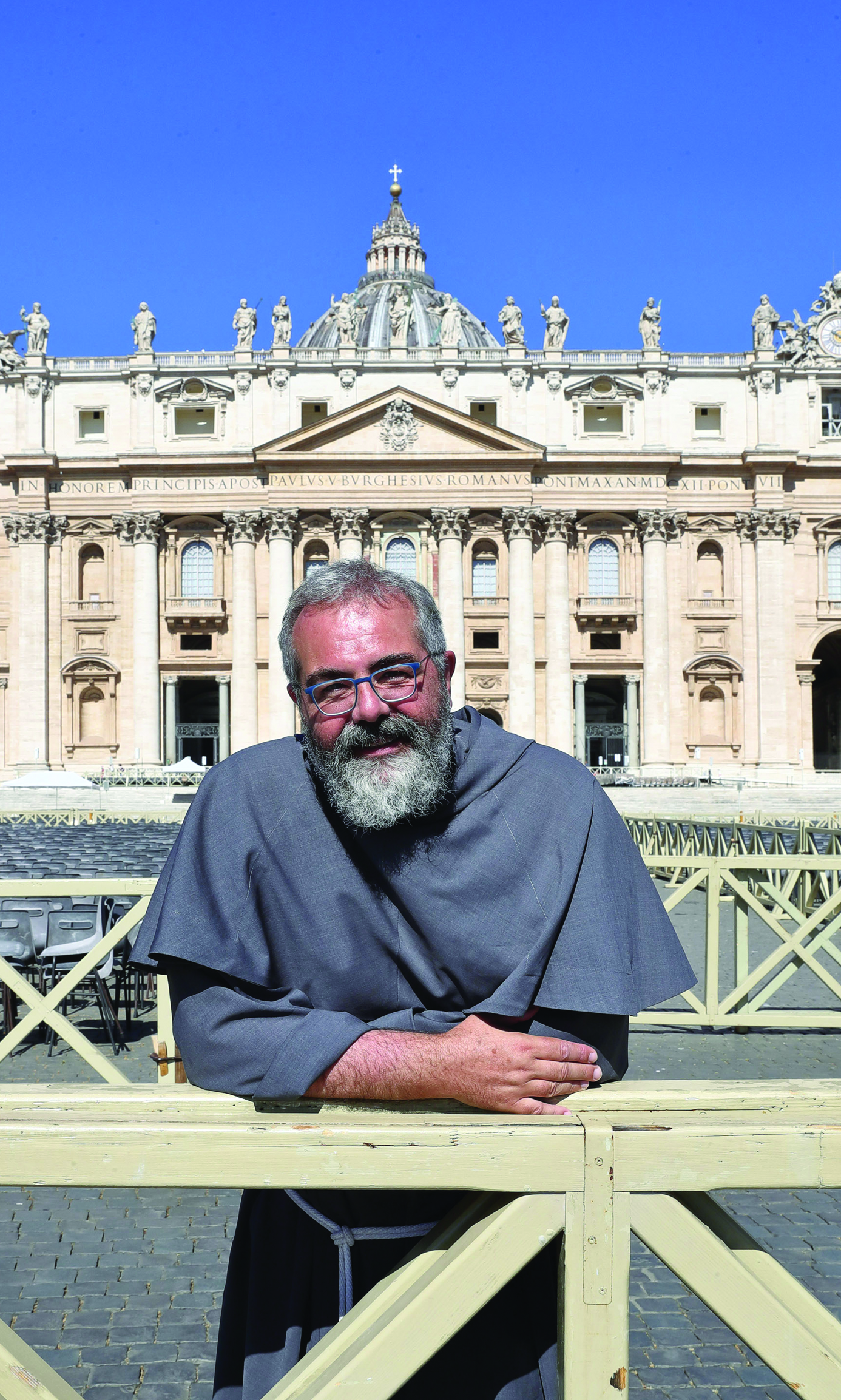

Maria Hildingsson.

“If you want to build peace, you cannot manage it without the family,” says Maria Hildingsson, Secretary General of the European Federation of Catholic Family Associations (FAFCE). Hildingsson is leading the charge for political representation of family interests from a Catholic perspective in the European Union’s governing bodies.

Born and raised in Sweden, Hildingsson moved to France in 1997, obtaining her Master’s degree in international relations at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes Internationales in Paris in 2004. She assumed her post at FAFCE in 2009.

Originally formed after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, FAFCE has been recognized by the Council of Europe, and has representatives from every EU member country. It was recognized as a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) with participative status in 2001 — the only explicitly Catholic NGO with this status in Europe.

Many Europeans assume that the EU government in Brussels does not affect their daily lives, but, in an interview in 2014, Hildingsson noted that about 70% of national laws actually originate at the European level. “I do think it’s important to underline how much power the EU actually has, although it can seem as if it is very far away, very abstract,” she says.

Unfortunately, the influence of the EU Parliament and the Council of Europe has not been benign toward the family.

One dramatic example is the Estrela Report. Portuguese member of parliament Edite Estrela drafted the text, which put reproductive “health”—including sex education starting at age zero, and free access to abortion, on a par with other human rights. It also refused the right of conscientious objection for medical staff who oppose technologies which violate the dignity of the person. Thanks in part to a vigorous campaign led by FAFCE, the Estrela Report was voted down in December 2013. Though non-binding, it could have paved the way to push this agenda on every EU nation.

FAFCE has tackled other related concerns in 2014, including the eclipse of the family by economic issues. While conceding the necessity of economic support, she says, “The Euro 2020 strategy is about work… but it is not based on a family perspective. It is rather about improving the competitiveness of European countries. The family is thus put aside.”

Hildingsson identifies three main groups among the EU Parliament members: those who see marriage as an institution intended to protect children and spouses, and another group which is, she says, “hostile to this idea.”

“But in between these groups,” she continues, “there is a huge group, a majority… who never, perhaps, paid much attention to these issues.” This group is, Hildingsson says, is “quite willing to listen to arguments, put forward with common sense, but also using facts and figures… many things we can promote in the European debate.”

Family breakdown threatens Europe socially, as it does the West in general. Hildingsson maintains that it “does not reflect the desires of the hearts of young people,” who “want to have a family, relationships that last a lifetime, and they respect adults who have been good parents and kept their families together.”

In fact, Hildingsson believes that a change in mindset might actually be underway in Europe. In the debate about same-sex marriage and children, she says, “I think it is very important to have a look at a map of Europe… you will see there is a rift which is growing bigger and bigger” between the former Warsaw Pact states, who resist these policies, and the wealthier Western European states, who pressure them to change in return for financial aid. “Sometimes there is true bullying,” she says.

But large popular protests against anti-family policies have not been limited to countries like Hungary and Croatia; witness in France the Manif Pour Tous (“Demonstration for All”) phenomenon of a million protesting technology-assisted reproduction. And in 2013, almost 2 million signed the “One of Us” initiative to stop EU funding of technologies that destroy human embryos.

“I lived in France for 13 years, and I can see that there is a change in the minds of people,” Hildingsson said. “This would not have happened five years ago, I think. It is a reaction that comes from the grassroots level, from normal people in the street who are actually starting to realize that they can make a change.” It is a realization that may not have happened, nor been acted upon, without the tireless efforts of Maria Hildingsson and her colleagues at the European Federation of Catholic Family Associations. Identifying the Catholic principle which forms the basis for their work, she concludes: “We cannot act from an individualistic perspective; we need to search for the common good.”

Facebook Comments