One of the leading economic historians of our time, Dr. Rupert Ederer, an expert on the thought of Father Heinrich Pesch, SJ (1854-1926), takes a look at our present economic crisis.

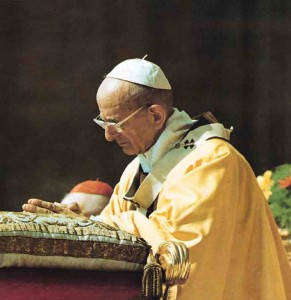

For anyone who takes Catholic social teaching seriously, specifically in the context of the present woeful condition of the American economy, it is necessary to focus on two statements during the recent era by men who found themselves in the leading magisterial position of the world’s oldest and largest Christian denomination. On May 14, 1971, Pope Paul VI addressed an apostolic letter, Octogesima Adveniens, to Cardinal Maurice Roy, president of the Council for the Laity and of the Pontifical Commission for Justice and Peace, commemorating the 80th anniversary of the 1891 encyclical of Pope Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum. After discussing a certain evolution which had taken place in acknowledged Marxist states by that time, the perceptive pontiff then turned to an ideological movement that was taking hold also in the non-Communist world.

On another side, we are witnessing a renewal of the liberal ideology. This current asserts itself both in the name of economic efficiency, and for the defense of the individual against the increasing and overwhelming hold of organizations, and as a reaction against the totalitarian tendencies of political powers. Certainly, personal initiative must be maintained and developed. But do not Christians who take this path tend to idealize liberalism in their turn, making it a proclamation in favor of freedom? They would like a new model, more adapted to present-day conditions while easily forgetting that at the very root of philosophical liberalism is an erroneous affirmation of the autonomy of the individual in his activity, his motivation and the exercise of his liberty. Hence the liberal ideology likewise calls for careful discernment on their part (35).

Pope John Paul II became even more specific about that theme in Mexico City on January 22, 1999 in his post-synodal apostolic exhortation Ecclesia in America. Addressing people in all of the Americas, he warned: “More and more in many countries of America, a system known as ‘neoliberalism’ prevails. Based on a purely economic conception of man, this system considers profit and the law of the market as its only parameters, to the detriment of the respect due to individuals and peoples” (56).

The man who, six years after his death on April 2, 2005, would be declared Blessed by his Church, warned prophetically that “…there is no authentic and stable democracy without social justice.” This was itself a significant acknowledgment by the Pope whom many are calling “great,” that authentic democracy must extend to the economic order as well as to the political system (56). It is perhaps reflected also in the recurring demonstrations by the 99% against Wall Street as the symbol of an excessively wealthy 1%.

Two contrasting images of the economy of the United States: the new poor in a poverty center and, pictured right, the world “temple” of modern capitalism, Wall Street, draped in an American flag. (Photos from CNS)

Capitalist plutocracies should be forewarned. They may well be facing some kind of parallel to the heinous outburst known as the French Revolution. That followed prolonged abuse of political power by long-standing hereditary monarchies and their associated aristocracies. The current murmur of revolution stems from the abuse of economic power by a class of capitalistic plutocrats nurtured in recent centuries by a cult of freedom which has come to be known as liberalism. Basically that is about freedom unhinged from reality — or truth.

Leo XIII: “…it may truly be said that it is only by the labor of the working man that States grow rich”

It was Leo XIII who laid the foundation for all subsequent Catholic social teachings on the economic order in his encyclical Rerum Novarum. He set forth basic concepts while not yet always using the precise terms which subsequently became formulaic for the Church’s social teachings, for example: the principle of subsidiarity, the terms just wage, preferential option for the poor, as well as social justice and social charity. That was accomplished by his successors, beginning notably with Pope Pius XI in Quadragesimo Anno. Accordingly, Rerum Novarum also did not contain the actual terms liberalism or economic liberalism, even though Leo XIII had indeed begun the Catholic Church’s opposition to economic liberalism in that encyclical. That had already been foreshadowed in his profound and important encyclical On Human Liberty (Libertas Praestantissimum) which came out in 1888. In it, he explained liberty as applied especially to the moral and political order, and he also referred there for the first time to “liberals” and “liberalism.”

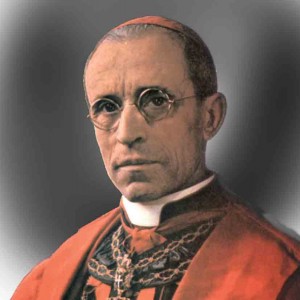

It was in the 1931 encyclical Quadragesimo Anno by Pope Pius XI, commemorating the 40th anniversary of Rerum Novarum, where economic liberalism specifically was to get its proper come-uppance. The Jesuit master economist, Father Heinrich Pesch, died in 1926, so he did not live to personally work on drafting that encyclical. However, two of his leading Jesuit understudies, Oswald von Nell-Breuning (1890-1991) and Gustav Gundlach (1892-1963), are known to have played a significant role in its development. Pesch had laid the groundwork not only for the demolition of the old liberalism as formulated and adapted in the works of, among others, the French Physiocrats, followed by Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill and the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Say. He had also already noted and opposed the early attempts to establish the new liberalism when that was being formulated by Ludwig von Mises after the old liberalism’s encounter with socialism prior to and following World War I. In the foreword to the fifth volume of his Lehrbuch der Nationalökonomie (1923), Pesch wrote (note: substitute the term liberalism for Manchesterism where the latter occurs): “People, not excluding learned economists, tend to lapse all too easily into extremes. The recklessness in socialistic free labor union policy did evoke and continues to evoke reaction, so that today one feels entitled to talk about a kind of ‘neo-Manchesterism.’ Mises is regarded as the main exponent of this trend, and because of his incisive and original criticism of socialism he has also gained acceptance and respect among authors who, unlike him, have stepped forward and supported the legal protection of women and children, and social insurance of workers.”

Pius XI: “Now it is of the very essence of social justice to demand from each individual all that is necessary for the common good”

Pesch continued: “Mises is on the wrong track when he attributes the terrible conditions in English factory regions where Manchesterism prevailed, not to that phenomenon, but to other circumstances. The historical development of industry among the various nations, and also a proper understanding of human nature, pass judgment on individualistic freedom.”

That was written five years after the end of World War I. (Ludwig von Mises, who was Jewish and born in what is now the Ukraine, had not yet been granted the von signifying some level of nobility.) The Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 had taken place in Russia, as had other short-lived Communist takeover attempts throughout Germany, Austria, and Hungary. Mises was capitalizing on middle-class fears that such events engendered, by demonstrating what he saw as the naturalness, therefore superiority, of what was then referred to among Germanic scholars as Neu-Manchesterthum (neo-Manchesterism) – and eventually as neoliberalism. Manchester represented a highly industrialized sector of the British economy during the 19th century. There two key figures, the industrialist Richard Cobden (1804-1865) and John Bright (1811-1899), were active in getting the Corn Laws repealed in Parliament, and then in promoting free trade and laissez-faire by their publications. Conditions in the factories there came to reflect the subsequent lawlessness.

In the years directly after World War II, Mises, with his confederate Friedrich von Hayek, a former socialist, exploited the worst fears about socialism then at large among capitalist sympathizers in the West. Such anxiety stemmed not only from the Cold War but also from the inroads which Keynesian economics had made during the period of the Great Depression and afterwards. The two are now widely hailed as “the Austrian economists,” and as “the Austrian School,” even though the leading members of the Austrian School (Karl Menger, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, Leopold von Wieser), designated as such for their prestigious status at the University of Vienna, had a wider range of interests. They made contributions that had little to do with the ideological campaign to restore free market economics.

What was made clear in Rerum Novarum, often referred to simply as “the labor encyclical,” was the singular importance of human labor among the factors of production. The reason, according to Pope Leo XIII, is: “…it may truly be said that it is only by the labor of the working man that States grow rich” (27).

Although this could and did lead to a variety of interpretations and conclusions, the three leading architects of economic systems, Adam Smith (The Wealth of Nations), Karl Marx (Das Kapital), and Heinrich Pesch (Lehrbuch der Nationalökonomie) basically concurred with that proposition, even though they did not derive the same conclusions or plans for action.

Smith promptly abandoned the well-being of the working class to the caprice of capitalists in reckless pursuit of their own self-interest by way of what he termed “the invisible hand.” Marx, on the other hand, sought eventual common ownership of all productive property along with the reduction of all classes to the proletariat. Only Pesch relied on the just wage in a context of solidarity among the owners of productive property and their workers. In this he was already building on the teaching of his Church as presented in Rerum Novarum by Leo XIII. Solidarity among the various productive classes was implicit in that encyclical. It was developed further and more explicitly in subsequent papal social teachings.

It was in Quadragesimo Anno by Pius XI in 1931 that any notion of “class conflict” and the “free play of rugged competition” were ruled out as the basis for social order and replaced by the twin virtues of “social justice and social charity” (88). The former was defined in 1937 by the same Pope in Divini Redemptoris, his encyclical On Atheistic Communism: “Now it is of the very essence of social justice to demand from each individual all that is necessary for the common good” (51). The definition of social charity, which he had identified in Quadragesimo Anno simply as “the soul” of the social order, remained inferential.

It was the now-Blessed Polish Pope John Paul II who in 1991 (Centesimus Annus) identified the principle of solidarity with social charity (10). That was after he had described solidarity exhaustively in Sollicitudo Rei Socialis in 1987 and declared it to be “undoubtedly a Christian virtue” (40). The essence of his newly-christened social virtue is the active concern for the common good stemming from the “awareness of interdependence among individuals and nations” (SRS 38).

As for liberalism, it was Pius XI who in Quadragesimo Anno first began to excoriate it in the economic order specifically as economic liberalism. Early in the encyclical (10), having identified its hallmark, “unrestrained competition,” he indicated that Leo XIII had “sought help from neither liberalism nor socialism.” Pius XI made the point then that liberalism “had already shown its utter incompetence to find a right solution to the social question…”; while socialism “…would have exposed human society to still graver dangers by offering a remedy much more disastrous than the evil it is designed to cure.”

Pius XII: “…without the cooperation of the public authorities, it is not possible to formulate an integral economic policy which would produce active cooperation on the part of all and an increase in industrial production.”

That was merely the opening salvo fired by the feisty pontiff against economic liberalism. He then referred specifically to the “tottering tenets of liberalism which had long hampered the effective intervention by the government” (27). Indeed “governments” presented a problem in that “not a few nations were much given to laissez-faire,” so that, among other things, they “regarded unions of workingmen with disfavor if not with open hostility” (30). When discussing “the social and public aspect of ownership,” Pius XI used the term “individualism” to characterize the situation where that “social and public aspect of property” is “denied or minimized” (46). Later, when the “unjust claims of capital” came under papal scrutiny, the Pope used the designation, “liberalistic tenets of the so-called Manchester School” (54).

Once again, this and some previous references clearly indicate the influence of Pesch’s Jesuit understudies behind the scenes in drafting Quadragesimo Anno. No one else had devoted such serious attention as Heinrich Pesch to the warped social philosophies which blocked healthy economic thinking in the period leading up to the actual socialist threat to the world emerging from World War I, and the subsequent great economic collapse in 1929. Examination of the philosophical fallacies underlying economic liberalism involved study also after the fact.

Where socialism was concerned, Pesch, who died in 1926, lived to compare his analysis of socialism both before and after its realization in history beginning in 1917. His earlier two-volume work on comparative social philosophies (Liberalism, Socialism, and Christian Social Order) appeared in German in 1899-1901. Then the first editions of relevant volumes of the Lehrbuch comparing economic systems were published between 1905 and 1913; revised later editions appeared in 1924 and 1925, after the Russian Revolution (1917).

Later in Quadragesimo Anno, Pius XI came to what may be termed his all-important definitive conclusion with regard to economic liberalism and the governance of economic life.

Just as the unity of human society cannot be built upon class conflict, so the proper ordering of economic affairs cannot be left to the free play of rugged competition. From this source, as from a polluted spring, have proceeded all of the unregulated errors of the “individualistic” school. This school, forgetful or ignorant of the social and moral aspects of economic activities, regarded these as completely free and immune from any intervention by public authority, for they would have in the market place and in unregulated competition a principle of self-direction more suitable for guiding them than any created intellect which might intervene. Free competition, however, though justified and quite useful within certain limits, cannot be an adequate controlling principle in economic affairs. (88)

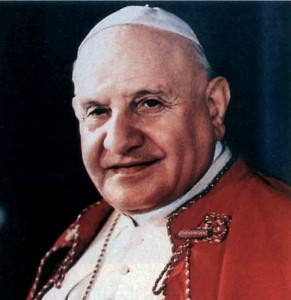

John XXIII: “The unregulated competition which

so-called liberals espouse, or the class struggle in the Marxist sense” are “utterly opposed to Christian teaching and also to the very nature of man”

With the socialist alternative already ruled out, that dispatches also Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” as the guiding principle in economic life. In Catholic social teachings, that palsied “hand” was now replaced once and for all with what Pius XI termed “more lofty and noble principles…: to wit, social justice and social charity” (88).

His immediate successor, the brilliant and saintly Pius XII, wrote no encyclicals addressed specifically to the economic order. He once explained his position in that regard by indicating that there were already enough great encyclicals stating the Church’s position on such matters, and that what was needed was more serious attention to putting the principles into operation. That did not deter him from offering frequent reminders about those principles. For example, early in his pontificate he reaffirmed the Church’s position with regard to economic liberalism. In an important encyclical-like Address to Italian Workers on June 1, 1941, commemorating the 50th anniversary of Rerum Novarum, we find his assertion that “…the errors and dangers of the materialist Socialist conception” were “the fatal consequences of Liberalism, so often unaware or forgetful, or contemptuous of social duties.” In 1942, in one of his masterful Christmas Messages, he referred to “liberal capitalism which marked Western civilization from the 18th century onward into the 20th century” as the “fateful economy of the past decades, during which the lives of all citizens were subordinated to the stimulus of gain…” A few years later, in 1948, addressing a Congress on International Exchange in Rome, Pius XII referred to the liberal ideology as “an appeal to an automatic and magic law” which was “no less vain in the economic order than in any other sphere of human activity.” Also, the exaggeration/distortion among neo-liberals in our own time of the principle of subsidiarity would find little encouragement in what Pius XII had to say about the role of the state in economic life. “Now, although the public authorities should not substitute their oppressive omnipotence for the legitimate independence of private initiatives, these authorities have in this matter an undeniable function of coordination, which is made even more necessary in the confusion of present conditions, especially social conditions.”

Paul VI: “Individual initiative alone, and the mere free play of competition, could never assure successful development”

Following what is now referred to as the Great Recession of 2008, it is fair to say that present-day conditions in economic life are no less confused, even chaotic, than they were when Pope Pius XII made that statement in a letter addressed to Semaine Sociale of Dijon, France, in 1952. He emphasized the point by indicating that “…without the cooperation of the public authorities, it is not possible to formulate an integral economic policy which would produce active cooperation on the part of all and an increase in industrial production.” That clearly puts limits on the way some interpret the principle of subsidiarity as a cover for the kind of liberalistic program which would simply exclude the state from any role in economic policy. Too easily forgotten is the fact that the principle of subsidiarity can be and often is flagrantly violated by omission as well as by commission! How often have not the higher authorities been forced into action because of malfeasance and neglect at the grassroots level?

In 1961, Pope John XXIII, now Blessed John XXIII, commemorated the 40th anniversary of Rerum Novarum by his one encyclical addressed to the economic order. Mater et Magistra marked 70 years since Rerum Novarum, and it repeated the censure of liberalism which began with that pioneer social encyclical of Leo XIII. From the outset, Pope John juxtaposed “human solidarity” in relations between workers and employers to “the unregulated competition which so-called liberals espouse, or the class struggle in the Marxist sense,” as “utterly opposed to Christian teaching and also to the very nature of man” (23). That bespeaks most eloquently also the naturalness of solidarity as developed by Heinrich Pesch — a concept that had begun to appear with increasing frequency in papal social teachings starting with Pope Pius XII. “Unrestricted competition” was censured again in a subsequent paragraph (35), where Pope John XXIII suggested that “because of its own inherent tendencies,” it “had ended up by almost destroying itself.”

Venerable Pope Paul VI, in addition to the aforementioned warning about the liberal ideology in his apostolic letter Octogesima Adveniens, had already dealt with it previously in his social encyclical, Populorum Progressio, in 1967. There he also made a critical and much-needed distinction between “industrialism itself” and “a type of capitalism” (26).

It is indeed an important distinction, because time and again some have erroneously attributed all of the undoubted benefits of the still ongoing Industrial Revolution (industrialism) to capitalism, and specifically, to free market capitalism. The two are distinct: the beginnings of capitalism preceded the Industrial Revolution by at least two centuries. Besides, some socialist ventures like the one in the Soviet Union after 1917 also brought with them a spectacular leap in industrial development (industrialism).

What Pope Paul VI deemed “unfortunate” was the construction of a system “which considers profit as the key motive for economic progress, competition as the supreme law of economics, and private ownership of the means of production as an absolute right that has no limits and carries no corresponding social obligations” (26). That happens to be a virtual description of economic liberalism. It is not surprising that a leading herald of neoliberalism, The Wall Street Journal, referred to the contents of Populorum Progressio, when it appeared, as “warmed over Marxism.”

The prophetic pontiff was not finished with free market capitalism. Inasmuch as the theme of Populorum Progressio was economic development, he ventured on to say here, “Individual initiative alone, and the mere free play of competition, could never assure successful development” (33). Also, “…the rule of free trade taken by itself is no longer able to govern international relations” (58). Then he offered this significant reminder with reference to international trade: “What was true of the just wage for the individual is also true of international contracts: an economy of exchange can no longer be based solely on the law of free competition, a law which, in its turn, too often creates an economic dictatorship.” The incisive conclusion was: “Freedom of trade is fair only if it is subject to the demands of social justice” (59).

As for Blessed John Paul II, one may safely characterize his great trilogy of social encyclicals in its entirety as a manifesto for a form of economy that goes beyond liberal capitalism. What else can one say of Laborem Exercens, his own labor encyclical which commemorates the 90th anniversary of the original one by Pope Leo XIII? There, in the third part, entitled Conflict Between Labor and Capital in the Present Phase of History, the Polish Pope noted that the conflict “found expression in the ideological difference between liberalism understood as the ideology of capitalism, and Marxism understood as the ideology of scientific socialism and communism…” (49). He established the reason for the ongoing conflict, as well as the priority of labor over capital, the neglect of which is the underlying cause of that conflict (52).

Karol Wojtyla had earned academic doctorates in both philosophy and theology, so that he understood well the “primacy of the person over things, and of human labor over capital, as a whole collection of means of production” (62). Based on his keen analysis of such matters, he reached a revolutionary conclusion in the subsequent portion of the encyclical: IV. On The Rights of Workers.

The Pope stated “… that the justice of the socioeconomic system and, in each case, its just functioning, deserve in the final analysis to be evaluated by the way in which man’s work is properly remunerated in the system” (89). As if to make it clear that he was referring to the same wage doctrine affirmed in previous encyclicals since Rerum Novarum, that is virtually repeated more specifically later in the same paragraph. “Hence, in every case, a just wage is the concrete means of verifying the justice of the whole socioeconomic system and, in any case, of checking that it is functioning justly.” Significant as this was, it received virtually no attention, due, perhaps, to the successful resuscitation of liberalism into neoliberalism as mentioned subsequently (1999) by the Polish Pope in his address Ecclesia in America.

Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, appearing six years after Laborem Exercens, is especially notable for its exhaustive explanation of solidarity which Pope John Paul II then declared to be “undoubtedly a Christian virtue” (40).

Later, in Centesimus Annus (10), the last of the great Pope’s trilogy of social encyclicals, he closed a great and important circle in his Church’s social teachings by identifying the “principle of solidarity” with social charity. Back in 1931, Pope Pius XI in Quadragesimo Anno (88) had established that virtue, along with social justice, as one of the two “lofty and noble principles” required for restoring order to economic life. It becomes clear then that the principle of solidarity which the Jesuit economist, Heinrich Pesch, placed at the core of his alternative solidaristic economic system, is in complete harmony with Catholic social principles for reconstructing social order.

John Paul II: “What was true of the just wage for the individual is also true of international contracts: an economy of exchange can no longer be based solely on the law of free competition, a law which, in its turn, too often creates an economic dictatorship.”

Finally, in a subsequent section of Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, Pope John Paul II made a statement that is relevant to the matter under discussion here. “For the Church does not propose economic and political systems and programs, nor does she show preference for one or the other, provided that human dignity is properly respected and promoted, and provided that she herself is allowed the room she needs to exercise her ministry in the world” (41). That, especially in the light of those two provisos (which I have italicized) is highly significant. Therein, to be sure, lies the justification for the Church’s taking a clearly negative position with regard to both liberal capitalism and Marxian socialism from the time it began its program of social teachings (1891) until now. Liberal and neo-liberal capitalism fails dismally on the first count; and Marxian socialism failed miserably on both counts!

At the same time, capitalism as such was never declared to be intrinsically evil in Catholic social teachings, because it is theoretically possible that capitalists, having become the dominant class in a society, could play by the rules, i.e., social justice and social charity.

Historically, however, that did not happen.

The ascendant capitalist class for the most part adopted the liberal ideology; and liberalism (both paleo- and neo-), as applied to the economic aspect of life, has been declared philosophically flawed and morally unacceptable (evil) from the start. Thus it would also vitiate any economic system where it predominates.

Incidentally, we may also perceive here the reason why Pius XI and all Popes following him have never publicly credited Heinrich Pesch for any of the principles of his solidaristic system which are found throughout the Church’s teachings addressing the economic order from the time of Pius XI until the present. “For the Church does not propose economic and political systems and programs, nor does she show preference for one or the other…”

Pesch, the author of the most exhaustive economics text ever written, was a qualified economist. Therefore he was acting within his proper jurisdiction in outlining an alternative economic system in accordance with specific principles.

The Popes of the Catholic Church, on the other hand, had to allow due leeway for competent persons to apply such essential principles in various and changing cultural contexts. Solidarist principles did indeed surface briefly during the post-World War I era in the Austrian economy under Chancellor Engelbert Dolfuss. His regime (1932-1934) was brief since he was assassinated by Austrian Nazis. It was referred to widely as the “Quadragesimo Anno State” (known in German also as the Ständestaat).

The last of the Blessed John Paul II trilogy of social encyclicals got more involved in the matter of identifying economic systems than perhaps any prior encyclical. As it turned out, Centesimus Annus (1991) was also the most widely misunderstood in this regard. Some neoliberals actually chose to see in it an endorsement of the free market economy in the neoclassical sense.

That, despite the fact that at its very outset Pope John Paul II reaffirmed the Leo XIII rejection of the way “…labor became a commodity to be freely bought and sold on the market, its price determined by the law of supply and demand without taking into account the bare minimum required for the support of the individual and his family” (4). In the same paragraph he indicated that “particular mention must be made of the Leonine encyclical Libertas Praestantissimum which called attention to the essential bond between human freedom and truth, so that freedom which refused to be bound to the truth would fall into arbitrariness and end up submitting itself to the vilest passions to the point of self-destruction.”

Here Blessed John Paul II cited this unhinged concept of liberty as “the origin of all evils to which Rerum Novarum wished to respond…”; and he termed it “…a kind of freedom which in the area of economic and social activity, cuts itself off from the truth about man.”

Indicated in the Catholic Church’s social teachings from the start, therefore, was the failure of the economic liberals, and now neoliberals, to observe “in the area of economic and social activity” the important link between the “truth about man.” That shortcoming gave birth to Marxian socialism, and now to the current and fatal capitalistic economic pandemonium.

The most recent social encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, by the present Benedict XVI, manifests the closing of a great circle in the Catholic Church’s social teachings.

We have here, among other things, a definitive example of the continuity in those teachings extending from Leo XIII until Pope Benedict XVI.

Caritas in Veritate has now addressed precisely the quintessential link between charity and truth which the earlier Pope expressed concern about in the pioneer social encyclical, Rerum Novarum.

And now, true to the entire more-than-one-century-old tradition of papal social encyclicals, the Bavarian Pope also reaffirmed a key principle affirmed by all Popes who have written such encyclicals. That is, in his words, “…especially the right to a just wage and to the personal security of the worker and of his or her family” (63).

Serious study of Caritas in Veritate, not to mention widespread implementation of that principle, has scarcely begun.

Facebook Comments