On April 19, 2005, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger was elected successor of Peter, choosing the name Benedict XVI. On April 19 this year, seven years will have passed. Let us celebrate these seven years.

In due time, scholars and wise observers will have many revealing things to say about the significance of Benedict XVI’s first seven years as pontiff (April 2005-April 2012). Here we would like to briefly develop two preliminary observations about these beginning years of the pontificate.

First, on the day after his election, with extraordinary clarity, Benedict outlined what he hoped to do as Pope. And what he set out to do on that day, he has done, year by year.

Second, in addition to this admirable demonstration of foresight and commitment, the seven years have had a special quality about them: constant, sensible, articulate statements about the Catholic faith. One might say they have an aroma of divine guidance, a sense of a providential presence.

Of course, the sense of God’s guiding hand has always been referred to by Joseph Ratzinger and was likewise an abiding reality in Karol Wojtyla’s life. But in terms of the seven years we are considering here, we are not talking about anything as openly and powerfully evident as what took place during John Paul II’s long papacy: things like the boundless evangelical confidence of John Paul in bringing to an end the chaos and confusion that had filled the Church in the years following Vatican II, nothing comparable to his role in the collapse of Communism and the breakup of the Soviet Union.

But in less noticeable ways, there has been a sense of Divine Providence at work from the outset of Benedict’s papacy, and even much earlier — back to his decision to join John Paul as a coworker.

To repeat, we will briefly touch on two seemingly providential subjects: the prevision of what Benedict said he would do as Pope, and the thrust of a few of his major undertakings.

Benedict’s Hopes for His Papacy

Benedict XVI’s most deeply-felt and comprehensive expression of his prayerful hopes for the future of his papacy were clearly stated in his address on April 20, 2005, to the cardinals who had just elected him the day before. This talk followed his first Mass as Pope and revealed to the cardinal-electors not only what was on his mind, but also what was in his heart.

In the afterglow of his stunning elevation to the Chair of Peter, Benedict described feeling John Paul’s strong grip squeezing his hand, seeing “his smiling eyes” and hearing his words: “Do not be afraid!” Almost simultaneously, he heard Peter’s words: “You are the Christ, the son of the living God” (Mt. 16:16). He described his overall feeling as being “totally dependent on the providence of God.” He then went on to list a series of goals he had for his pontificate, beginning with his “commitment to enact” the teachings of Vatican Council II.

After quoting Council documents on the Mass and Eucharist, he said he was convinced that the fact that his election took place during the year John Paul had designated as “The Year of the Eucharist” was part of God’s plan. He reminded the cardinals that the Eucharist is “the heart of Christian life and the source of the evangelizing mission of the Church.” Therefore, it would necessarily be at the heart of his papacy — “the permanent center and the source of the Petrine service entrusted to me.”

He encouraged the cardinals to openly and strongly express their own love and devotion to the Eucharistic Jesus and the Real Presence of the Lord. “I ask this in a special way of priests, about whom I am thinking in this moment with great affection.” He then turned to Christian unity, promising to work “tirelessly towards the reconstitution of the full and visible unity of all Christ’s followers.”

What was foremost in his mind for the Church was to speak in Christ’s voice, to “revive within herself an awareness of her task to speak to the world again with the voice of the One who said: ‘I am the light of the world’ and ‘No follower of mine will ever walk in the darkness. No, he shall possess the light of life’ (John 8:12). The Church is and must remain Christocentric.”

He then reached out to the world of non-Christians, expressing concern for those “who follow other religions or who are simply seeking an answer to the fundamental questions of life and have not yet found it.” He continued: “I address everyone with simplicity and affection, to assure them that the Church wants to continue to build an open and sincere dialogue with them.”

Working toward his conclusion, he returned to Christ, pleading that He abide with the Church and his pontificate. He quoted the prayer of the disciples: “Mane nobiscum, Domine! Remain with us, Lord!” (Luke 24:29). He pointed out that John Paul II’s Apostolic Letter for the Year of the Eucharist (2004) also employed this invocation. Benedict again added a personal note, telling them that the prayer had “spontaneously come from my heart as I turned to begin the ministry to which Christ has called me. Like Peter, I too renew to Him my unconditional promise of faithfulness. Him alone I intend to serve as I dedicate myself totally to the service of His Church.”

He ended by appealing to Saints Peter and Paul, then calling on “the maternal intercession of Mary Most Holy, in whose hands I place the present and the future of my person and of the Church.”

In the following days he would again and again underline his connection with John Paul, saying in one interview: “My personal mission is not to issue many new documents, but to ensure that his documents are assimilated, because they are a rich treasure.” He stressed that, for John Paul, “the world was his parish” and that he created “a new sensitivity for moral values and the importance of religion in the world.” Six years later, May 1, 2011, in his homily at John Paul’s beatification, he would say: “In God’s providence, my predecessor died on the vigil of this feast” — the feast of Divine Mercy.

Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz, John Paul’s personal secretary, struggled to find the words to explain the relationship between John Paul II and Ratzinger, but saw very clearly that there was a strong bond of love and dependence on God: “There is a certain something, I can’t find the right word — they were more than collaborators — it was something that was much deeper, a spiritual unity. Both were men of great faith and also of great love towards Christ.”

Once again, the key words in John Paul and Benedict’s reference to their collaboration are God’s presence and his providence.

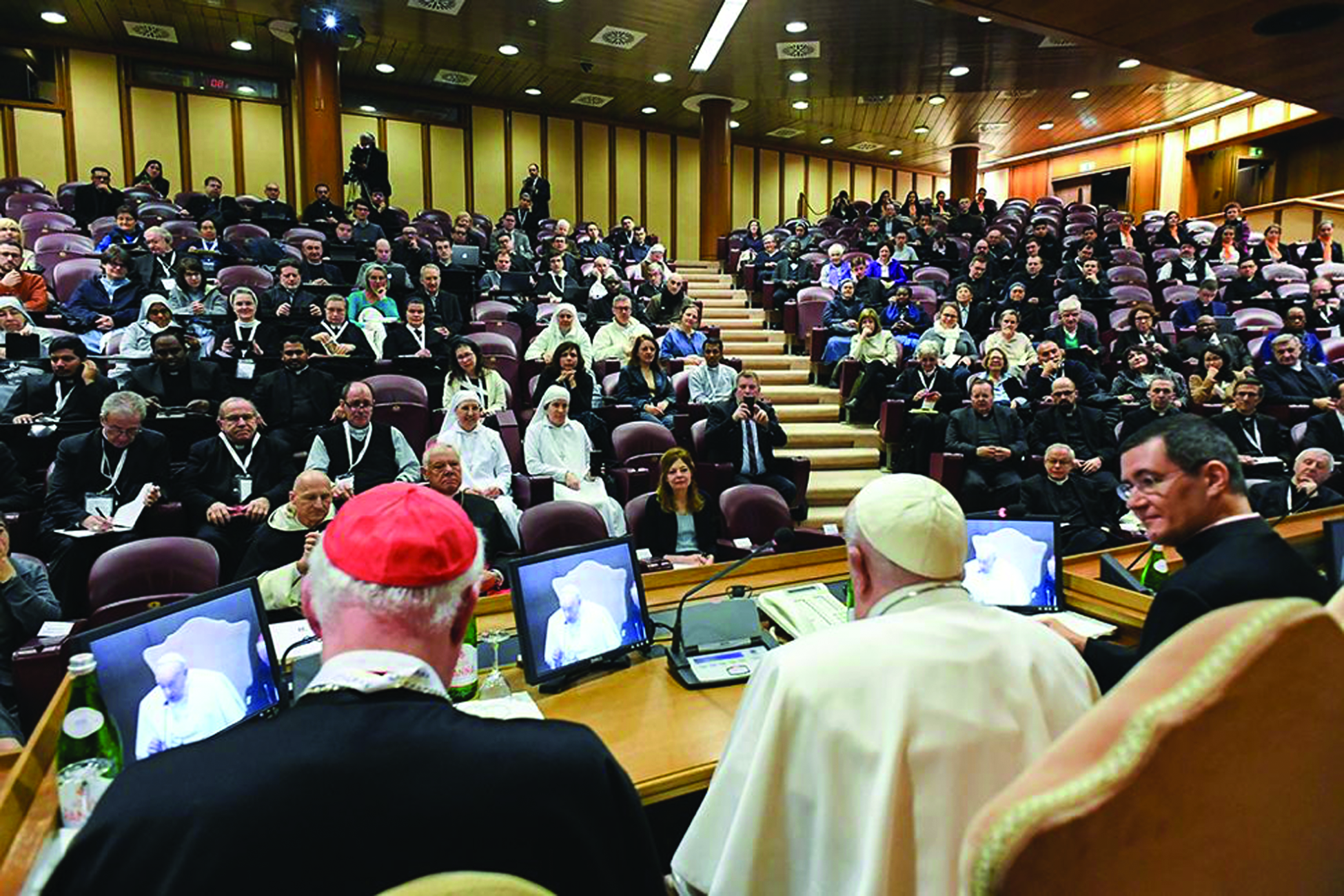

Pope Benedict.

There is no question that John Paul II has had considerable influence on Benedict’s first seven years. Thus it would be important to understand this influence by trying to look more closely at how they came to work together and some of the possible effects of those 24 years of extremely close cooperation.

However, the initial inspiration behind their becoming coworkers was entirely John Paul’s; the cardinal appears to have been very reluctant. The difficulty may seem a little strange in that he had little difficulty accepting his appointment as archbishop of Munich and Freising. He said in his autobiography Milestones that he had seen “a connection between my previous task as teacher and my new mission.” And, he decided, with the help of a confessor, that despite all the differences between being a professor and being an archbishop of a major diocese, “what was involved was and remains the same: to follow truth” (p. 153).

On various occasions, Ratzinger has said that he was concerned that becoming a member of the Curia would prevent him from writing major theological studies.

Wojtyla and Ratzinger would have known of each other at Vatican II, but they evidently never met and talked. Several sources inform us that Wojtyla did read Ratzinger’s classic study of the Creed, Introduction to Christianity, and was impressed by it. He was also impressed by the theological positions Ratzinger took against more liberal Catholic theological theories in the 1970s. They did have a very cordial meeting at a bishops’ synod in 1977 and then they apparently had more extended talks in 1978, at the time of the conclave that elected John Paul I.

After John Paul’s election on October 16, 1978 , when he was forming his Curia, he asked Archbishop Ratzinger to join him in Rome. Ratzinger told him it was too soon for him to leave his post as archbishop, and as a professor who hoped to do more theological writing. The Pope asked him to think more about his request and said he would talk to him again. Then came the assassination attempt on May 13, 1981.

The still-recovering Pope again called to invite the German cardinal to Rome. He now had a new argument, namely, that curial cardinals in the past had written independently-minded scholarly works while serving in the Curia. In other words, being in the Curia would not deprive Ratzinger of the right to express individual judgments.

Still, it would seem, Archbishop Ratzinger found it painful to leave his post in Munich. Peter Seewald, author of three books of interviews with Ratzinger, tells us something about Ratzinger’s reluctance.

He reveals that Ratzinger’s final homily before leaving for Rome raised questions about the Church needing changes and about the very human desire to lead as simple and uncomplicated a life as possible, “like everyone else.”

Unfortunately, when Seewald asked the cardinal to comment on that sermon, Ratzinger said he could not because he had no clear memory of it (Salt of the Earth, pp. 87-88).

It’s clear that Ratzinger always had the utmost respect for the wishes of Christ’s vicar. A Pope deserves abiding loyalty from the faithful. An invitation from him must be given the utmost attention. In his conversations with John Paul, he always found him very warm and open, and a man of deep faith.

Then there was the other reality: this Pope had nearly been martyred and was still suffering from the assault. Ratzinger agreed to go to Rome in February of 1982.

It is hard to believe that Ratzinger would not have been moved by the horrifying assassination assault of May 13, 1981. In any case, the two men agreed that the cardinal would become the Pope’s “coworker in truth” — as the motto on Ratzinger’s coat of arms described the archbishop of Munich and Freising. Inevitably, John Paul saw the hand of Providence in his new coworker’s decision, much as he was profoundly certain that the miraculous intercession of Mary had saved his life.

John Paul’s attitude towards Cardinal Ratzinger’s decision to serve in Rome was very simple: “I thank God for Cardinal Ratzinger.”

Looking back, one can wonder what John Paul’s papacy would have been like if, in 1981, Ratzinger had been “like everyone else” and had not been willing to take on an endlessly demanding job. If that had been his view, he would, in all likelihood, have not become Pope. Similarly, if he had followed his original desire to concentrate on theological writing, it is very unlikely that he would have become the teacher to the globe that he has become, influencing a massive audience around the world. And his theological writing would never have had the “bestseller” prize that his first two volumes, Jesus of Nazareth, have had.

Though the Jesus of Nazareth volumes are presented under the name of Joseph Ratzinger, a great deal of their commercial success has to be attributed to the fact that they are written by a very articulate and learned Pope.

Of course, the two cannot be entirely kept separate. Inevitably the books, as full of faith and learning as they are, tell a much more fresh and comprehensive story of Jesus than any Vatican document could.

The volumes have an artistry that brings Jesus, the human and divine Person, alive.

And it is not only the depiction of Jesus Christ, the person and the Son of God, but also an endless catalog of fascinating human beings: his apostles, his opponents, the vacillating multitude, in an endless series of ordinary, joyous and tragic encounters.

The volumes convey divinity and humanity in the greatest of all contexts — the Almighty Father’s powerful love for humanity.

The scholarship, which puts a century of historical-critical research into an understandable context, is simply a bonus for the more academic readers to agree with or to reject. For the serious reader, the volumes are continually informative and extremely rewarding reading.

As for seven years of Benedict’s papal documents, they are largely concerned with deepening faith and restoring order in matters like the Eucharist and the Liturgy and with encouraging the faithful to higher and deeper levels of belief, piety and respect for all of the Church’s life and worship.

His encyclicals Deus Caritas Est (“God is Love”), December 25, 2006; Spe Salvi (“Saved by Hope”), November 30, 2007; and Caritas in Veritate (“Charity in Truth”), June 29, 2009, treat of the essential Christian beliefs in God, Christ, faith, hope, charity and truth. They reflect Benedict’s concern not only for Catholics, but for all Christians, and for all non-Christians as well.

Perhaps the most important of his disciplinary documents are: 1) the November 2005 Instruction in which he sought to support the purity of a celibate priesthood by issuing a document that had long been delayed: “Concerning the Criteria for Discernment of Vocations with Regard to Persons with Homosexual Tendencies”; and 2) the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum, issued on July 7, 2007, that restored the Traditional Latin Mass as an alternative to the reformed Mass of 1970. He hoped that by making the traditional Mass available to all Catholics that it would help bring about “an interior reconciliation in the heart of the Church.”

It would take volumes to properly substantiate the impact of such documents. Hopefully it will be sufficient to make one obvious point: Benedict, writing as Pope or as theologian, is in the service of the One who said: “I am the light of the world.”

No one can say with certainty what would or would not have happened if the cardinal had not come to Rome. But knowing what we know, we can say it has led to seven years of evangelical, world-wide pastoring and to spiritual counsel that might best be seen as a remarkable example of the working of Divine Providence.

Another, simpler conclusion is that each of the seven years has had the indelible character of Benedict’s homilies, essays and books — orderliness, reasonableness and inspiration drawn from Scripture, “pressed down, shaken together, running over” (Lk: 6:38).

Benedict’s years do not mark a Great Jubilee in accord with Leviticus (25:8-12), where God commands the remission of debts and accompanying actions, but they do mark a “jubilee” according to today’s very broad use of the word, namely, any of a variety of personal and institutional accomplishments that are worthy of praise and gratitude. The key to the new meaning is that the anniversary is worthwhile and merits a joyous celebration, which sums up Benedict’s pontificate.

The main things which are not joyous about Benedict’s pontificate are the scandalous and sinful actions of many Catholics, and those occasional incidents and words that have been twisted and misinterpreted. Like death and taxes, there is nothing that can be done about tabloid journalists twisting and misinterpreting words and actions.

Therefore, April 19 may rightly be seen as marking a period of resurgence, of rooting out past evils and scandals and of returning to the essential message of the Gospel, of honoring the central person in human history — Jesus Christ.

It should be celebrated joyously.

Facebook Comments