…and in Beijing, the gesture is “noted.” The full text of a controversial recent papal interview

Pope Francis gave his first-ever interview on China and the Chinese people on January 28 to Asia Times columnist and China Renmin University senior researcher Francesco Sisci, which follows.

In the historic one-hour interview at the Vatican the Pope urged the world not to fear China’s fast rise. He said the Chinese people are in a positive moment and delivered a message of hope, peace and reconciliation as an alternative to war, hot or cold.

The pontiff also sent Chinese New Year’s greetings to the Chinese people and President Xi Jinping, the first extended by a Pope to a Chinese leader in 2,000 years.

In response, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Lu Kang said he had “noted the relevant report.”

“China has always been sincere about improving Sino-Vatican ties, and has made many efforts in this regard,” Lu told a daily news briefing.

“We are still willing to have constructive dialogue with the Vatican based on this principle, meeting each other halfway, and keep pushing forward the development of the process of improving bilateral relations. We also hope that the Vatican can take a flexible, pragmatic attitude to creating conditions for improving ties.”

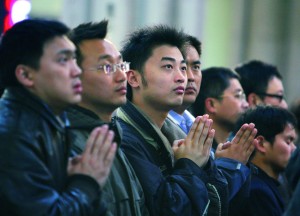

Those preparing to become Catholics are recognized by the congregation during a Sunday Mass at St. Ignatius Cathedral in Shanghai, China (CNS photo/Nancy Wiechec)

The Vatican, which has had no formal diplomatic ties with Beijing since the Communist takeover of 1949, has repeatedly expressed its desire to engage the Chinese in discussions, while still struggling to defend the rights of Chinese Catholics, still victims of discrimination and outright persecution.

“The Chinese are polite, and we are also polite. We are doing things step by step,” said Pope Francis in an early 2014 press conference while flying through Chinese air space — a first for a Pope.

The Chinese, he added, “know that I am ready to go there [to China] or to receive [Chinese officials] at the Vatican.”

Particular sticking points in the Vatican’s often-tense relations with Beijing include Beijing’s insistence that Beijing, not Rome, has the authority to appoint Catholic bishops in China. In 1957, the Chinese government created a parallel church called the Catholic Patriotic Association, heavily regulated by the Communist Party, which claims the right to all episcopal appointments.

Nina Shea, director of the Center for Religious Freedom at the Hudson Institute, points out that Shanghai Auxiliary Bishop Thaddeus Ma Daquin has been under house arrest since July 2012, when he announced at his consecration Mass that he was resigning from the Catholic Patriotic Association.

Shea notes that since the end of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, “the Christian population has skyrocketed, with credible estimates ranging between 70 and 100 million. The government-registered-and-heavily-regulated Catholic Patriotic Association counts a mere 6 million of these as Catholic.”

“Another 6 million are thought to be members of the underground Catholic Church,” she says, going on to say the Vatican has “discouraged” membership in it — though no explicit communiqué to that effect has even been issued.

Shea may be referring to a letter written by Pope Benedict XVI to the faithful of China in 2007, in which, in the cause of reconciliation, he initiated the process of Vatican approval of many of the bishops installed by the Chinese government.

The move was seen by some as “discouraging” for the underground Catholic Church: as a September 2015 report in the Hong Kong Free Press pointed out, “For many in the Underground Church, the letter sent a discouraging message, implying that their devotion was rendered pointless by the fact that bishops in the Open Church enjoy both an extent of freedom from the government and the seal of legitimacy from the Vatican. On the other hand, for Catholics in the Open Church the motivation to push for greater freedoms for their underground brothers and sisters diminishes: why search for underground Masses and risk the chance of being imprisoned when you can worship openly in cathedrals?”

Despite the inconclusive nature of negotiations thus far, the Holy See’s unwavering concern for China can be seen in even subtle ways: in every single major Papal Mass since Pope Francis’ election, from his own inaugural Mass to Easter and Christmas vigils every year, one of the several languages in which intercessory prayers have been said — for either grace in the hearts of politicians or for increases in priestly vocations — has always been Mandarin.

Francesco Sisci of “Asia Times” interviews Pope Francis at the Vatican with papal staffers

“China has always been a reference point for greatness”

By Francesco Sisci

I asked for an interview on broad cultural and philosophical issues concerning all Chinese, of whom more than 99% are non-Catholic. I didn’t want to touch on religious or political issues, of which other Popes, at other times, had spoken.

I hoped he could convey to common Chinese his enormous human empathy by speaking for the first time ever on issues that worry them daily — the rupture of the traditional family, their difficulties in being understood by and in understanding the Western world, their sense of guilt from past experiences such as the Cultural Revolution, etc. He did it and gave the Chinese and people concerned about China’s fast rise reasons for hope, peace and conciliation with each other.

What is China for you? How did you imagine China to be as a young man, given that China, for Argentina, is not the East but the far West? What does Matteo Ricci mean to you?

Pope Francis: For me, China has always been a reference point of greatness. A great country. But more than a country, a great culture, with an inexhaustible wisdom. For me, as a boy, whenever I read anything about China, it had the capacity to inspire my admiration. I have admiration for China. Later I looked into Matteo Ricci’s life and I saw how this man felt the same thing in the exact way I did, admiration, and how he was able to enter into dialogue with this great culture, with this age-old wisdom. He was able to “encounter” it.

When I was young, and China was spoken of, we thought of the Great Wall. The rest was not known in my homeland. But as I looked more and more into the matter, I had an experience of encounter which was very different, in time and manner, to that experienced by Ricci. Yet I came across something I had not expected.

Ricci’s experience teaches us that it is necessary to enter into dialogue with China, because it is an accumulation of wisdom and history. It is a land blessed with many things. And the Catholic Church, one of whose duties is to respect all civilizations, before this civilization, I would say, has the duty to respect it with a capital “R.” The Church has great potential to receive culture.

The other day I had the opportunity to see the paintings of another great Jesuit, Giuseppe Castiglione — who also had the Jesuit virus (laughs). Castiglione knew how to express beauty, the experience of openness in dialogue: receiving from others and giving of one’s self on a wavelength that is “civilized,” of civilizations. When I say “civilized,” I do not mean only “educated” civilizations, but also civilizations that encounter one another. Also, I don’t know whether it is true but they say that Marco Polo was the one who brought pasta noodles to Italy (laughs). So it was the Chinese who invented them. I don’t know if this is true. But I say this in passing.

This is the impression I have, great respect. And more than this, when I crossed China for the first time, I was told in the aircraft: “Within ten minutes we will enter Chinese airspace, and send your greeting.” I confess that I felt very emotional, something that does not usually happen to me. I was moved to be flying over this great richness of culture and wisdom.

A statue of Jesuit Father Matteo Ricci stands outside the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Beijing (CNS photo/Nancy Wiechec)

China, for the first time in its thousands of years of history, is emerging from its own environment and opening to the world, creating unprecedented challenges for itself and for the world. You have spoken of a third world war that is furtively advancing. What challenges does this present in the quest for peace?

Being afraid is never a good counselor. Fear is not a good counselor. If a father and a mother are fearful when they have an adolescent son, they will not know how to deal with him well.

In other words, we must not fear challenges of any kind, since everyone, male and female, has within them the capacity to find ways of co-existing, of respect and mutual admiration. And it is obvious that so much culture and so much wisdom, and in addition, so much technical knowledge — we have only to think of age-old medicinal techniques — cannot remain enclosed within a country; they tend to expand, to spread, to communicate. Man tends to communicate, a civilization tends to communicate. It is evident that when communication happens in an aggressive tone to defend oneself, then wars result.

But I would not be fearful. It is a great challenge to keep the balance of peace. Here we have Grandmother Europe, as I said in Strasbourg. It appears that she is no longer Mother Europe. I hope she will be able to reclaim that role again. And she receives from this age-old country an increasingly rich contribution.

And so it is necessary to accept the challenge and to run the risk of balancing this exchange for peace. The Western world, the Eastern world and China all have the capacity to maintain the balance of peace and the strength to do so. We must find the way, always through dialogue; there is no other way. (He opens his arms as if extending an embrace.)

Encounter is achieved through dialogue. The true balance of peace is realized through dialogue. Dialogue does not mean that we end up with a compromise, half the cake for you and the other half for me. This is what happened in Yalta and we saw the results. No, dialogue means: look, we have got to this point, I may or may not agree, but let us walk together; this is what it means to build. And the cake stays whole, walking together. The cake belongs to everyone, it is humanity, culture. Carving up the cake, as in Yalta, means dividing humanity and culture into small pieces. And culture and humanity cannot be carved into small pieces. When I speak about this large cake I mean it in a positive sense. Everyone has an influence to bear on the common good of all. (The Pope smiles and asks: “I don’t know if the example of the cake is clear for the Chinese?” I nod: “I think so.”)

China has experienced over the last few decades tragedies without comparison. Since 1980 the Chinese have sacrificed that which has always been most dear to them, their children. For the Chinese these are very serious wounds. Among other things, this has left enormous emptiness in their consciences and somehow an extremely deep need to be reconciled with themselves and to forgive themselves. In the Year of Mercy, what message can you offer the Chinese people?

The aging of a population and of humanity is happening in many places. Here in Italy the birth rate is almost below zero, and in Spain too, more or less. The situation in France, with its policy of assistance to families, is improving. And it is obvious that populations age. They age and they do not have children.

In Africa, for example, it was a pleasure to see children in the streets.

Here in Rome, if you walk around, you will see very few children. Perhaps behind this there is the fear you are alluding to, the mistaken perception, not that we will simply fall behind, but that we will fall into misery, so therefore, let’s not have children.

There are other societies that have opted for the contrary. For example, during my trip to Albania, I was astonished to discover that the average age of the population is approximately 40 years. There exist young countries; I think Bosnia and Herzegovina is the same. Countries that have suffered and opt for youth.

Then there is the problem of work. Something that China does not have, because it has the capacity to offer work both in the countryside and in the city.

And it is true, the problem for China of not having children must be very painful; because the pyramid is then inverted and a child has to bear the burden of his father, mother, grandfather and grandmother.

And this is exhausting, demanding, disorientating. It is not the natural way. I understand that China has opened up possibilities on this front.

Bishop Paul Lei Shiyin, holding crosier on right, poses with other clergymen after being ordained bishop of Leshan. Bishop Lei was ordained without a papal mandate at Our Lady of the Rosary Church in Emeishan, reported the Asian church news agency UCA News. (CNS photo/courtesy Diocese of Leshan, UCAN)

How should these challenges of families in China be faced, since they find themselves in a process of profound change and no longer correspond to the traditional Chinese family model?

Taking up the theme, in the Year of Mercy, what message can I give to the Chinese people? The history of a people is always a path. A people at times walks more quickly, at times more slowly, at times it pauses, at times it makes a mistake and goes backwards a little, or takes the wrong path and has to retrace its steps to follow the right way.

But when a people moves forward, this does not worry me because it means they are making history. And I believe that the Chinese people are moving forward and this is their greatness. It walks, like all populations, through lights and shadows. Looking at this past — and perhaps the fact of not having children creates a complex — it is healthy to take responsibility for one’s own path.

Well, we have taken this route, something here did not work at all, so now other possibilities are opened up. Other issues come into play: the selfishness of some of the wealthy sectors who prefer not to have children, and so forth. They have to take responsibility for their own path. And I would go further: do not be bitter, but be at peace with your own path, even if you have made mistakes. I cannot say my history was bad, that I hate my history. (The Pope gives me a penetrating look.)

No, every people must be reconciled with its history as its own path, with its successes and its mistakes. And this reconciliation with one’s own history brings much maturity, much growth. Here I would use the word mentioned in the question: mercy. It is healthy for a person to have mercy towards himself, not to be sadistic or masochistic. That is wrong. And I would say the same for a people: it is healthy for a population to be merciful towards itself. And this nobility of soul … I don’t know whether or not to use the word forgiveness, I don’t know. But to accept that this was my path, to smile, and to keep going. If one gets tired and stops, one can become bitter and corrupt. And so, when one takes responsibility for one’s own path, accepting it for what it was, this allows one’s historical and cultural richness to emerge, even in difficult moments.

And how can it be allowed to emerge? Here we return to the first question: in dialogue with today’s world. To dialogue does not mean that I surrender myself, because at times there is the danger, in the dialogue between different countries, of hidden agendas, namely, cultural colonizations. It is necessary to recognize the greatness of the Chinese people, who have always maintained their culture. And their culture — I am not speaking about ideologies that there may have been in the past — their culture was not imposed.

Children gather with parish priests for a photo on the steps of Sacred Heart of Jesus Church in the village of Fufengxian, in China’s Shaanxi province, in late July. The Catholic parish was marking its 17th anniversary in a region known for its apple groves. (CNS photo)

The country’s economic growth proceeded at an overwhelming pace but this has also brought with it human and environmental disasters which Beijing is striving to confront and resolve. At the same time, the pursuit of work efficiency is burdening families with new costs: sometimes children and parents are separated due to work. What message can you give them?

I feel rather like a “mother-in-law” giving advice on what should be done (laughs). I would suggest a healthy realism; reality must be accepted from wherever it comes. This is our reality; as in football, the goalkeeper must catch the ball from wherever it comes. Reality must be accepted for what it is. Be realistic. This is our reality. First, I must be reconciled with reality. I don’t like it, I am against it, it makes me suffer, but if I don’t come to terms with it, I won’t be able to do anything. The second step is to work to improve reality and to change its direction.

Now, you see that these are simple suggestions, somewhat commonplace. But to be like an ostrich that hides its head in the sand so as not to see reality, nor accept it, is no solution. Well then, let us discuss, let us keep searching, let us continue walking, always on the path, on the move. The water of a river is pure because it flows ahead; still water becomes stagnant. It is necessary to accept reality as it is, without disguising it, without refining it, and to find ways of improving it. Well, here is something that is very important. If this happens to a company which has worked for 20 years and there is a business crisis, then there are few avenues of creativity to improve it. On the contrary, when it happens in an age-old country, with its age-old history, its age-old wisdom, its age-old creativity, then tension is created between the present problem and this past of ancient richness.

And this tension brings fruitfulness as it looks to the future. I believe that the great richness of China today lies in looking to the future from a present that is sustained by the memory of its cultural past. Living in tension, not in anguish, and the tension is between its very rich past and the challenge of the present which has to be carried forth into the future; that is, the story doesn’t end here.

On the occasion of the upcoming Chinese New Year of the Monkey, would you like to send a greeting to the Chinese people, to the authorities and to President Xi Jinping?

On the eve of the New Year, I wish to convey my best wishes and greetings to President Xi Jinping and to all the Chinese people. And I wish to express my hope that they never lose their historical awareness of being a great people, with a great history of wisdom, and that they have much to offer to the world. The world looks to this great wisdom of yours. In this New Year, with this awareness, may you continue to go forward in order to help and cooperate with everyone in caring for our common home and our common peoples. Thank you!

Francesco Sisci

Francesco Sisci, Asia Times columnist and a senior research associate of China Renmin University, also served as Asia Editor for the Italian daily La Stampa and as Beijing correspondent for Il Sole di 24 Ore. This interview originally appeared on the Asia Times website at atimes.com/2016/02/at-exclusive-pope-francis-urges-world-not-to-fear-chinas-rise.

SAINTS

Open God’s heart with prayer, Pope tells Padre Pio Prayer Groups

Prayer is not a business negotiation with God, the Pope told more than 60,000 people gathered in St. Peter’s Square on February 6. Prayer is a “work of spiritual mercy,” a time to entrust everything to the heart of God, he said.

The pilgrims were in Rome for the Year of Mercy and a week of special events that included veneration of the relics of St. Padre Pio and St. Leopold Mandic (see photo), both Capuchin friars who often spent more than 12 hours a day hearing confessions.

Although many faithful believe the body of Padre Pio, who died in 1968, is incorrupt, Church officials have never made such a claim. When his body was exhumed in 2008, Church officials said it was in “fair condition.” Chemicals were used to ensure its long-term preservation and the face was covered with a silicone mask.

Pushed through the center of Rome February 5 in glass coffins on rolling platforms, the relics of Padre Pio and St. Leopold were escorted by Italian military police, dozens of Capuchin friars and thousands of faithful.

When the procession reached St. Peter’s Square — the boundary of Vatican City State — the Italian police stood at attention and the Swiss Guard took over the honor-guard duties. Cardinal Angelo Comastri, archpriest of St. Peter’s, welcomed the relics, blessed them with incense and accompanied them into St. Peter’s Basilica where they were to stay for veneration until February 11.

At the papal audience, joining members of the Padre Pio Prayer Groups from around the world were staff members of the hospital he founded, the Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza (House for the Relief of Suffering), whose work is supported by the prayers and donations of the prayer groups.

Pope Francis told them that their devotion to Padre Pio should help them rediscover each day “the beauty of the Lord’s forgiveness and mercy.” With his long hours in the confessional, the Pope said, “Padre Pio was a servant of mercy and he was full-time, carrying out the ‘apostolate of listening’ even to the point of fainting.”

“The great river of mercy” that Padre Pio unleashed, he said, should continue through the prayers and, especially, the willingness to listen and to care for others shown by members of the prayer groups.

If prayer were just about finding a little peace of mind or obtaining something specific from God, then it would basically be motivated by selfishness: “I pray to feel good, like I’d take an aspirin,” the Pope said.

“Prayer, rather, is a work of spiritual mercy that carries everything to the heart of God” and says to Him, “You take it, you who are my Father.” Padre Pio, he said, used to tell people prayer is “a key that opens God’s heart.”

“God’s heart is not armored with all sorts of security measures,” the Pope said. “You can open it with a common key — prayer.” — Cindy Wooden (CNS)

Facebook Comments