Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Buenos Aires, Argentina, just after being made cardinal at the consistory of February 21, 2001, 14 years ago.

There is, in Buenos Aires, a “papal tour” bus that takes visitors around places linked to the life of Jorge Bergoglio, from those of his youth—his baptismal church, family home, and schools—to those of his adulthood: a seminary where he recuperated after his life was saved at age 21, and the cathedral seat of once-Archbishop Bergoglio.

Austen Ivereigh is well placed to write The Great Reformer, a literary papal tour of the life of Pope Francis. Ivereigh was once a Jesuit, as was the Pope, and he knows Francis’ Argentina intimately: he took his Oxford D.Phil. on Catholicism and politics in Argentina, particularly between 1930 and 1960. The two men share a common concern for evangelization, too. Francis’s first apostolic exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium, focuses on the “proclamation of the Gospel in today’s world.” Ivereigh is a career journalist who was press secretary to a cardinal and co-founder of Catholic Voices (through which organization I have come to know him).

Moreover, putting these strands together, the biographer shares his subject’s passions, for instance over the plight of immigrants. Bergoglio was the son of Italian migrants whose parents set sail for prosperity in the “land of silver” when clouds were gathering over Europe in the late 1920s. The Great Reformer duly starts with a description of the newly elected Pope’s first journey outside of Rome, to the Mediterranean island of Lampedusa, the tragic crossroads currently at the center of a refugee crisis where many refugees have drowned while attempting to cross the sea on packed, decrepit boats run by human traffickers.

Francis, in his visit, “wept for the dead and made migration a pro-life issue,” writes Ivereigh. “Maybe they reminded him of the time many years before he was born when five hundred passengers, almost all in steerage class, drowned off the northeast coast of Brazil.”

All this makes for a very sympathetic biography. In the main, this is not in the least bit troubling: the sympathy brings out Bergoglio’s decency, without failing to acknowledge that a man who was polite and pious (he was at one point nicknamed el santito, “the little saint”) was also considered by many as “publicity-shy and aloof” and someone who scorned the middle classes.

So who is the man, Jorge Bergoglio?

Born into a middle-class family in the 1930s, Jorge was instilled with piety, particularly by his grandmother. He enjoyed reading and football as a child, and the later pleasures of dancing and courting. His adolescent cultural formation took place against the backdrop of Colonel Peron’s coup in 1943, which framed the rest of Argentina’s short century. Peron wanted greater enfranchisement and a consumer democracy without fascist or communist overtones, and wound up delivering Argentine politics into a mix of periodic economic meltdown, junta-governed military oppression, and the “dirty war” against political dissidents and suspected socialists that erupted in the 1970s.

Jorge entered the Jesuits in the mid-1950s, becoming a novice, priest, novice master, professor of theology, and finally the regional Provincial Superior in short order.

A constant refrain is that Francis has always been or sought to be a unifier of conflicting interests. He superintended the growth in the order in Argentina and was an active participant in the Jesuits’ internal struggles in the flux that followed the Second Vatican Council, facing down priests from the radical left who sneered at the orthodoxy of Bergoglio’s formation programs (“sandals yes, books no”). (At one point, Bergoglio managed to get expelled from the Jesuit university in Buenos Aires, losing his teaching post and accommodation, precipitating an explosion of the Society into factionalism.)

Yet we know that Bergoglio cannot be characterized as a bogeyman of the right. Ivereigh deals crisply and cleanly with the historical accusations that Bergoglio sold out his fellow Jesuits during the dirty war, and somehow aided the military dictatorship. The truth is that Bergoglio, through a Jesuit network across Latin America, helped many hundreds escape torture and death; the accusations only resurfaced in 2005 in a dirty tricks campaign to destroy his chances of succeeding John Paul II.

Ivereigh is keen to emphasize that mercy lies at the heart of Francis’s understanding of Christianity. He has frequently proclaimed today a new time for forgiveness—Kairos. This cannot happen without community. Bergoglio described the specific Jesuit task as being to train and encourage lay people through the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises, and, in Ivereigh’s words, to “create institutions of belonging.” Aged 50, Bergoglio discovered, in a sabbatical in Germany cut short through loneliness and homesickness, that he is “a deeply rooted and connected person who needed community.”

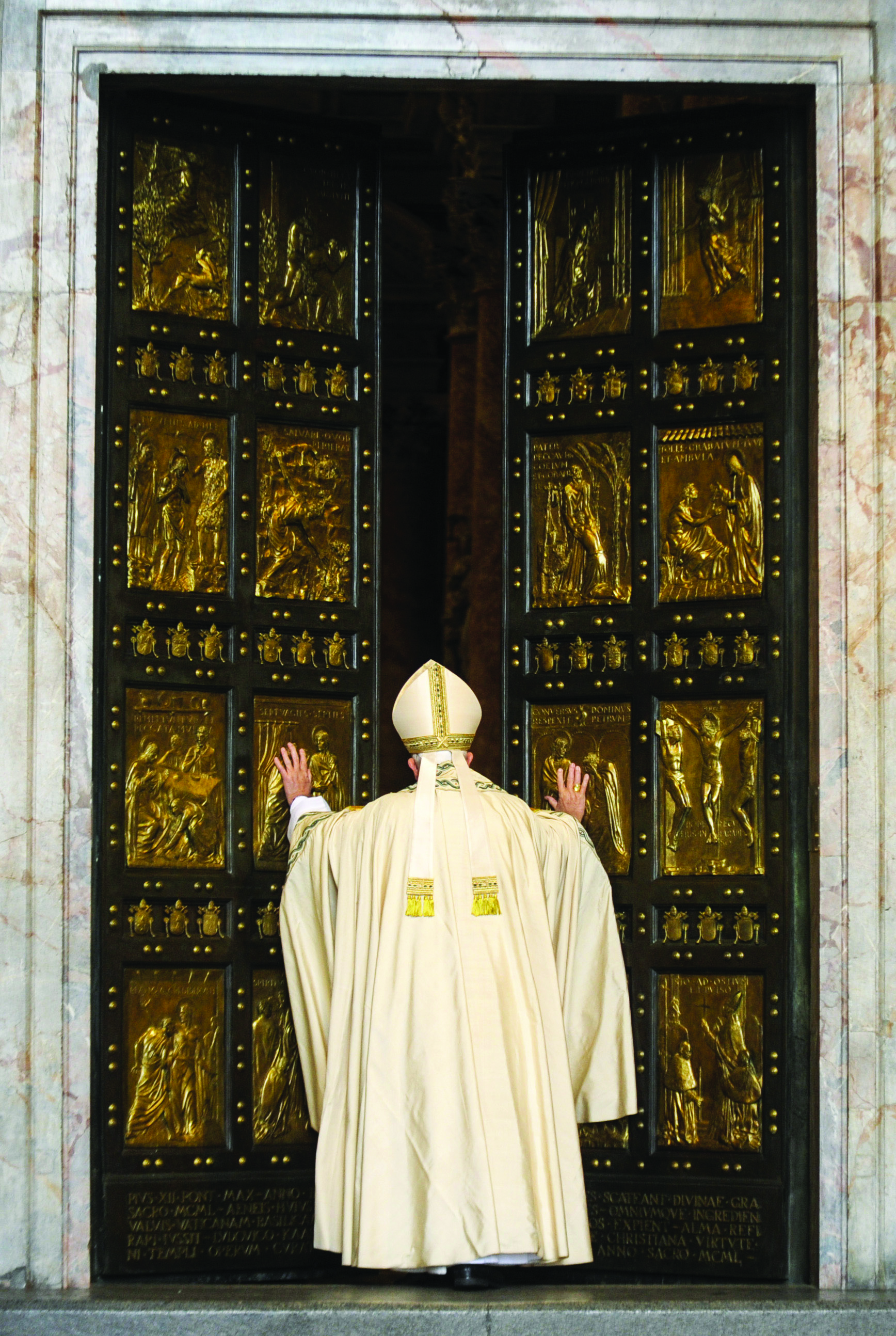

Bergoglio often employs the vivid language of injury and healing, perhaps driven by his own frailty and the parallels (of a young man recovering from trauma) with St. Ignatius Loyola, the Jesuits’ founder. After graduating from secondary technical college with a talent for chemistry, Bergoglio reneged on a promise to his mother to become a doctor. With “proto-Jesuit deftness” he told her, “I didn’t lie to you, Mom … I’m going to study medicine of the soul.” Over 35 years later, in a letter written shortly before becoming a bishop, he described his religious vocation as “like being thrown from a horse.” As Pope, he told crowds in St Peter’s Square that “a Church that doesn’t have the capacity to surprise is a weak, sickened and dying Church. It should be taken to the recovery room at once.” Most famously, he compared the Church to a military field hospital that tended to the injured.

A reader of Bergoglio’s life would unlikely guess that he was the eldest of five, for his traits of cheekiness and risk-taking give the impression of his being the youngest. There are glimpses throughout his life: a passionate letter as a child to the girl next door to marry her if he didn’t become a priest; the openness to traditional Chinese medicine; a dislike of Rome (he did not visit the Sistine Chapel until the 2005 conclave); the preference for an image of Our Lady as the “untier of knots”; the insistence that it was better to have a Church that “made mistakes and got dirty than one that stayed inside”; the willingness to give away power rather than accumulate it.

It’s hard to generalize over the Pope’s politics but, at a pinch, the Pope sits in that space overlapped by moral conservatism and social liberalism. He is insistent on Humanum Vitae and on community justice, and strongly influenced by Pope Paul VI’s view in Evangelii Nuntiandi that there is no faith without justice. He has an affirmed confidence in the preferential option for the poor, and was willing to put his own life in danger when evangelizing in the slums (this preference for real, concrete actions over abstractions is one of four principles the Pope seems to have discerned in his life, and which are set out in Evangelii Gaudium).

Yet he does not let the corpus of writing on solidarity or the common good in the canon on Catholic Social Teaching get in the way of subsidiarity. He has a firm belief that the ecclesiastical structure of the Church should slide away from the Roman-centric “Petrine” model espoused under Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI, to authority and decision-making rooted in the diocese (the “Pauline” model). Francis prefers bishops to fight national moral campaigns without the Pope.

Undoubtedly, there has been a sea change in the Vatican. As Pope, Francis has shown a new face to the survivors of child abuse and has been feted as ‘man of the year’ by numerous secular publications across the globe. The images of the Pope hugging disfigured and disabled people are famous around the world. Throughout his life, he has had strong and good relations with leaders of other faiths, particularly Jews and Muslims, and connections with Protestants, particularly evangelicals, as well as charismatics within the Catholic Church. All of this ecumenism is set to continue, and be complemented by widespread curial reform.

But his desire to speak to the heart can sometimes cause Francis to err. When his bugbear, Nestor Kirchner, late husband of Cristina, introduced a same-sex marriage law in 2010, Bergoglio urged “revising and extending the concept of civil unions, as long as this left marriage intact.” Simply opposing the measure, he thought, would be politically unappealing unless it was accompanied by “an alternative that advanced civil rights for gay people.” The problem, of course, was that no alternative existed. Arguably, in his bid to be the emotive healer of discord, he was blind to the power politics and the need, on occasion, not to seek compromise but to stand one’s ground in opposition.

Ivereigh contends that Francis’ “freewheeling communication and his proclamation in a missionary key” mean “putting love and mercy and healing first, before rules and doctrines.” That’s dangerous, for the role of Supreme Pontiff is precisely to provide coordination between the various parts of the Church so it can grow, act, and prosper in concert. It’s very hard to do this without rules.

Ivereigh, too, has his blind spots. He is unduly harsh on the “exhausted” Pope Emeritus, describing Benedict as presiding over “Catholicism’s increasingly tired and desolate centre,” and approving of the cry, at the 2013 conclave, for a “big broom” to sweep out the Vatican. In all, however, Austen Ivereigh has produced an interesting and perceptive book that covers thoroughly the life — thus far — of Jorge Bergoglio.

Editor’s note: This essay first appeared on quadrapheme.com on 11/27/14 and is reprinted with permission. Copyright © 2014 Center for Morality in Public Life. All Rights Reserved.

Facebook Comments