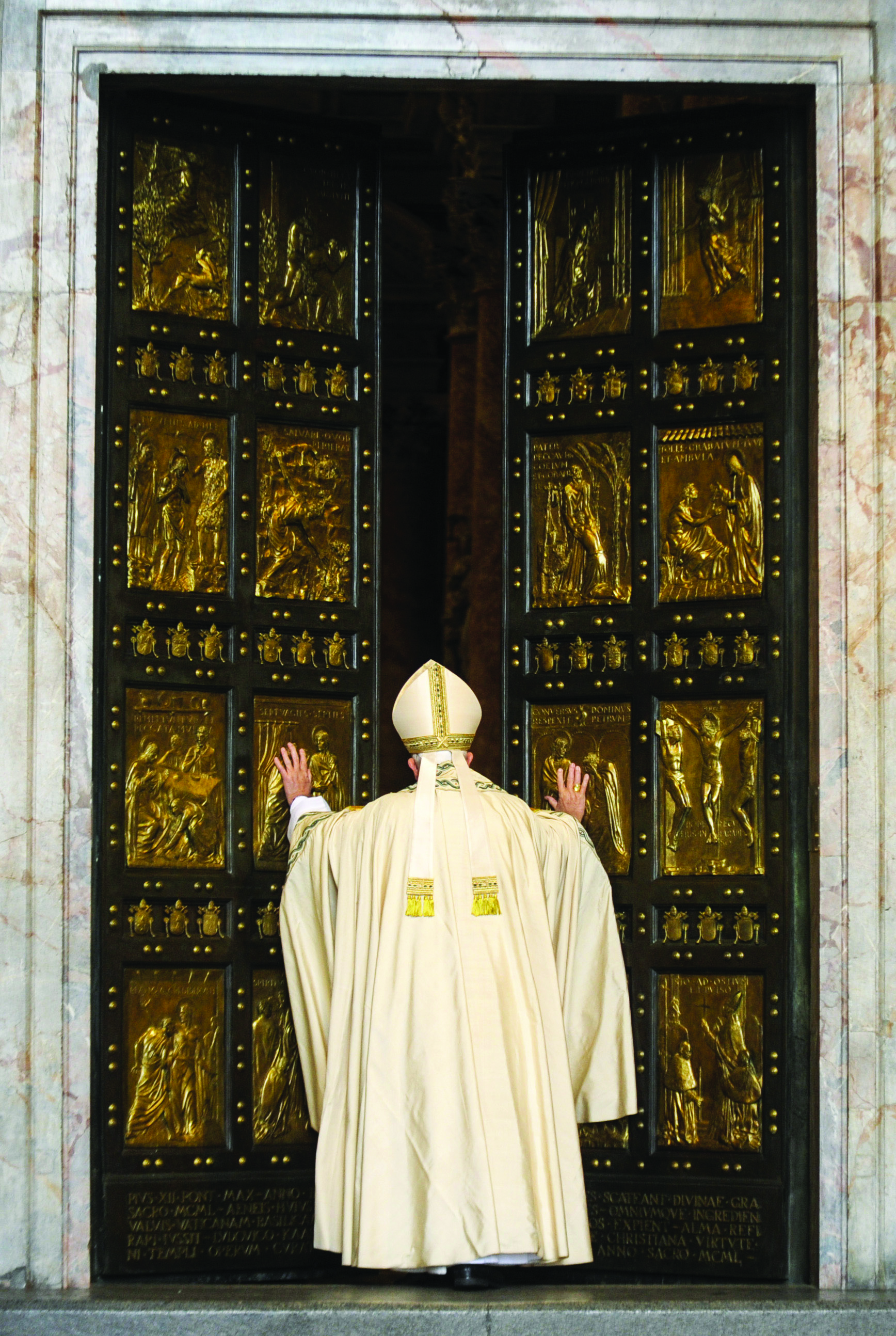

Almost every September, Pope Benedict delivered a profound, dramatic address to the political and academic world. His cry: “The windows must be flung open again.”

Pope Benedict. (Galazka photo)

We can call them Benedict’s “September speeches.” Pope Benedict pronounced them during the trips he took each year, after the summer vacation, to different European capitals. The meetings with the political and academic world are considered essential to understanding the Pope’s philosophical and political thinking. The golden thread is always the relationship between faith and reason. From Germany to Germany, from Regensburg in 2006 to Berlin in 2011, via Paris and London. From university to university: Regensburg, Rome, Prague.

In Regensburg in 2006, the yearning of journalists to file a “scoop” cast a shadow over Benedict’s remarkable speech, developed around the core that “not to act in accordance with reason is contrary to God’s nature.” That speech was intended to be a “signature statement” for Benedict’s papacy, launching the theme of “broadening our concept of reason and its application,” in order to overcome the dichotomy between a reason relegated to the experimental field and a faith limited to the spiritual sphere. It was such a statement — but few have yet understood it.

The same question was at the center of a lecture prepared for the (canceled) visit to the University of Rome “La Sapienza” in January 2008: “If reason (…) becomes deaf to the great message that comes to it from Christian faith and wisdom, then it withers (…), it loses the courage for truth and thus becomes not greater but smaller.”

In September 2009, at the Collège des Bernardins in Paris, in a wonderful address that took origin from the roots of monasticism, Benedict XVI spoke about “quaerere Deum” — the search for God.

He pointed out that “a purely positivistic culture which tried to drive the question concerning God into the subjective realm, as being unscientific, would be the capitulation of reason, the renunciation of its highest possibilities, and hence a disaster for humanity (…).” He continued: “What gave Europe’s culture its foundation — the search for God and the readiness to listen to him — remains today the basis of any genuine culture.”

The political philosophy of Benedict XVI is based on these concepts, as they appear in his London and Berlin speeches.

In London in 2010, he spoke to Britain’s elite in Westminster Hall: “Where is the ethical foundation for political choices to be found? The Catholic tradition maintains that the objective norms governing right action are accessible to reason, prescinding from the content of revelation.” So the role of religion in public debate, he argued, is “to help purify and shed light upon the application of reason to the discovery of objective moral principles (…). The world of reason and the world of faith (…) need one another and should not be afraid to enter into a profound and ongoing dialogue for the good of our civilization.” In other words, “it is not a problem for legislators to solve, but a vital contributor to the national conversation.”

In September of 2009, the Pope spoke in Prague: “There comes the temptation to detach reason from the pursuit of truth. Sundered from the fundamental human orientation towards truth, however, reason begins to lose direction.”

At the Bundestag in Berlin in 2011, Benedict XVI faced the issues of right and justice. Again the question: “How do we recognize what is right?”

Christianity, he said, “has never proposed a revealed law to the State and to society” but “it has pointed to nature and reason as the true sources of law.”

The problem is that “where positivist reason considers itself the only sufficient culture (…), it diminishes man, indeed it threatens his humanity (…). In its self-proclaimed exclusivity, the positivist reason which recognizes nothing beyond mere functionality resembles a concrete bunker with no windows, in which we ourselves provide lighting and atmospheric conditions, being no longer willing to obtain either from God’s wide world. And yet we cannot hide from ourselves the fact that even in this artificial world, we are still covertly drawing upon God’s raw materials, which we refashion into our own products. The windows must be flung open again.”

Be aware that we are creatures, and respect our nature: this is the way indicated by the Pope.

The same way that made Europe great: “The conviction that there is a Creator God is what gave rise to the idea of human rights.”

A theme that resounded some years before, in April 2008, when the Pope visited the UN headquarter on the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “They (human rights) are based on the natural law inscribed on human hearts and present in different cultures and civilizations. Removing human rights from this context would mean restricting their range and yielding to a relativistic conception.”

As history proceeds, “new situations arise, and the attempt is made to link them to new rights. Discernment, that is, the capacity to distinguish good from evil, becomes even more essential.” It is the same invitation we find at the end of the address at the Bundestag: like the young King Solomon, “even today, there is ultimately nothing else we could wish for but a listening heart — the capacity to discern between good and evil, and thus to establish true law, to serve justice and peace.”

Facebook Comments