Anne de Bretagne,

Queen of France, commissioned this

prayer book for her son Charles-Orland in c. 1494

On display in a splendid exhibition called “Illuminating Faith: The Eucharist in Medieval Life and Art” until September 2 are 65 of the some 1,300 medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts belonging to New York’s Morgan Library. Here illuminating means both decorating with miniatures but also explaining the changes of this central act of Christian worship. These changes begin with the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, which codified Transubstantiation — that during Mass the substances of bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Christ — and required every Christian to receive Communion at least once a year. These are followed by the establishment in 1246 of a new Eucharistic feast: Corpus Christi, commemorated annually on the Thursday following Trinity Sunday, and by Pope Eugene IV’s gift of the Sacred Bleeding Host in 1433 to Duke Philip of Burgundy; its cult flourished over the next 350 years.

“Illuminating Faith,” which sadly has no catalog, is divided into six thematic sections: Institution of the Eucharist, Celebration of Mass, The Eucharist and the Old Testament, Domestic Devotion to the Eucharist, Feast of Corpus Christi, and Eucharistic Miracles. It features manuscripts from France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and Hungary as well as medieval religious objects: a chalice, ciborium, pax, very rare altar card, and two monstrances (used to display the Eucharistic Host) on loan from the Metropolitan Museum.

In chronological order, its “stars” are three, according to Roger S. Wieck, curator of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts and of this exhibition. The earliest was commissioned in c. 1494 by the well-educated, later patron of the arts and collector of tapestries including the “Unicorn Tapestries” now in the Cloisters in New York, Anne de Bretagne, Queen of France (1477-1514).

It’s a small prayer book to teach basic catechism to her first-born son, the Dauphin Charles-Orland who, aged three, died suddenly of the measles in 1495. Purchased by J.P. Morgan in 1905, this codex, written in Latin and French and on display in Domestic Devotion to the Eucharist, contains prayers, like the Lord’s Prayer and the Hail Mary, that the Queen intended to help her son memorize, as well as others he was to read on his own as he grew up. Jean Poyer, one of France’s foremost early Renaissance artists who worked for the French court, illuminated it.

Priest Elevating the Host, detail from the Tiptoft Missal.

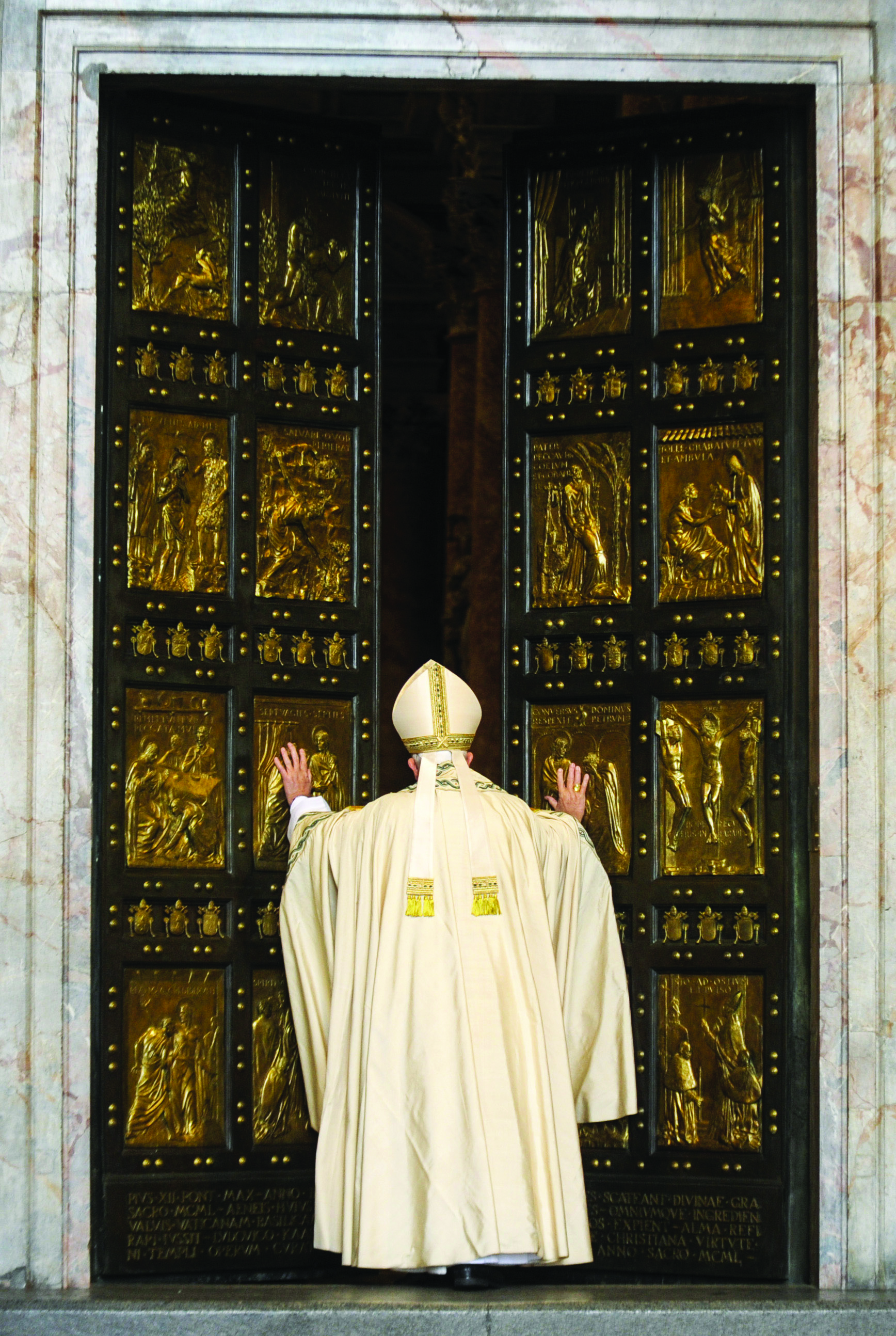

The second “star” is the Preparation for the Mass (“Preparatio ad missam”) of Pope Leo X. Born Giovanni de’ Medici, Leo X’s life and papacy is the subject of my story in this same issue which celebrates his election as Pope 500 years ago.

This lavish manuscript in Latin, commissioned by Leo X himself in 1520, is displayed in Celebration of Mass. According to Wieck, “it contains the prayers the Pope would recite as he prepared himself for celebrating Mass in the Sistine Chapel… This manuscript, identifiable in an eighteenth-century inventory of the papal sacristy, remained in the Vatican until 1798, when it was looted by Napoleon’s troops.” It came to the Morgan Library in 1977 as a gift from the Heineman Foundation.

Purchased by J.P. Morgan in 1903, the third “star” is the Hours of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, who commissioned it in 1546. One of the greatest of all illuminated manuscripts, otherwise known as the “Farnese Hours,” in “Illuminating Faith” it’s opened to the litany of Corpus Christi, which is illustrated with the papal procession at Old St. Peter’s showing Pope Paul III Farnese, grandfather of Alessandro, carried on a litter and holding a monstrance. It should be noted that, although Pope Urban IV instituted Corpus Christi as a universal Church feast in 1264, his death two months after his promulgation interrupted the feast’s dissemination. Corpus Christi became widespread only after Clement V reconfirmed the bull in 1311, and his successor, John XXII, published it in 1317.

On display are several other highlights. One, in Celebration of Mass, is the luxurious “Tiptoft Missal,” probably made in Cambridge, England, c. 1320 with decoration on each of its 360 leaves. It’s a rare survivor because, following the establishment of the Church of England, most of that country’s medieval Mass books were destroyed.

Pope Leo X’s Preparatio ad missam showing the Medici coat of arms under the illumination of the Pope’s preparation for Mass.

There are several other rarities in Celebration of Mass. One is an altar card in Latin made in Paris c. 1520 and illuminated by the workshop of Jean Pinchore. Given to the Morgan in 2006 by an anonymous donor in honor of Don Emerson, it’s the most recent gift to this department of the Library. “Altar cards assisted the priest during Mass,” Dr. Wieck explained to me at the press preview. “Propped up against the back of the altar, their practical format freed the celebrant’s hands from flipping through his Missal at critical moments of the ceremony. This card along with one in the Philadelphia Free Library forms one of the earliest sets known.”

As I mentioned earlier, after the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, believers were required to receive Communion at least once a year. This usually happened around Easter. In Celebration of Mass three miniatures depict different versions of this celebration.

A leaf from the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX, made in Bologna in 1330-35, depicts the Elevation, a ritual introduced in the early thirteenth century. Before that, men and women attending Mass had little to see and not much to hear. As Dr. Wieck explained, “Here the priest, bowing before the altar, whispers the sacred words of the Consecration. All eyes of those within the crowded church, as well as those of the people crammed onto the porch outside, turn expectantly toward the altar. In suspenseful anticipation, they await the moment of Elevation, when the priest will hold the Host over his head. As people in the Middle Ages generally received Communion only once a year, seeing the consecrated Host became a substitute — a kind of spiritual communion. People sometimes ran from church to church to witness as many Elevations as possible.”

A miniature in a Book of Hours in Dutch dating to 1445-60 shows a couple receiving Communion. “In the early Church,” Dr. Wieck continued, “people received Communion in their hands (a practice revived after the Second Vatican Council), but in the Middle Ages, lay people were forbidden to touch the Host, which is why here the priest places the wafer on the man’s tongue. Around Easter, when most people would take their annual Communion, the wafers might be distributed after Mass so as not to disrupt the service.”

Making a bad Communion due to improper fasting, or the lack of true contrition for sins committed, could invalidate Communion’s worthy reception and thus lead to damnation. A miniature from an Italian Book of Hours shows a contrite confession, thus a good Communion, with souls being welcomed by angels while on the opposite side of the illumination’s altar, after a false confession and ensuing bad Communion, souls are being hijacked by devils.

The Sacred Bleeding Host of Dijon Adored by a Couple from the Heures à l’usage de Romme, printed in Paris, 1501

The illuminations on display in The Eucharist and the Old Testament depict people, events, or things that foreshadowed the same in the New Testament. For example, the Sacrifice of Isaac prefigured the Crucifixion; and the miraculous food, manna, the Eucharist.

The exhibition’s final section concerns Eucharistic miracles. Most “reveal… the True Presence, which, theology explains, is the containment of the body and blood of Christ within the consecrated bread and wine of the sacrament.”

Several of the volumes here concern the Sacred Bleeding Host of Dijon, Dr. Wieck’s field of expertise.

“Bleeding hosts,” explained Wieck, “were the most convincing miracles that revealed—literally—the True Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Of the many medieval Communion wafers that oozed Christ’s blood, the Sacred Host of Dijon was the most visually arresting.” Given in 1433 by Pope Eugene IV to Duke Philip of Burgundy, he installed it in Dijon’s ducal palace chapel, which he renamed Ste.-Chapelle to rival its famous namesake in Paris. The Host became the city’s holy talisman, credited with saving Dijon in times of war, plague, and drought. It was the focal point for the city’s annual Corpus Christi processions when it was carried through the streets to neighboring churches. Much of what we know about the Dijon Host comes from a seventeenth-century monograph here on display, Sauvegarde du ciel pour la ville de Dijon, ou, Remarques historiques et chrestiennes sur la saincte e miraculeuse Hostie by Philibert Boulier, a priest and canon in the Ste.-Chapelle.

Another book printed in 1753 possibly contains the last known image of the Host, which French Revolutionaries burned in 1794.

Nonetheless, in 1825 a Mass of Reparation was established and to this day is celebrated annually in Dijon on February 10, the anniversary of the Host’s destruction.

Facebook Comments