Mark Riebling’s book lays to rest forever the accusation that Pope Pius XII (Eugenio Pacelli) was “Hitler’s Pope.” It shows how Pius XII collaborated for years with conspirators who were determined to assassinate Hitler. The book could be more aptly titled Church of Assassin Accomplices.

THE CONSPIRACY

The future Pope Pius XII was the Pope’s Nuncio to Germany in the 1920s. Here, Archbishop Eugenio Pacelli (the future Pope) and his secretary,

Father Leiber, in 1929

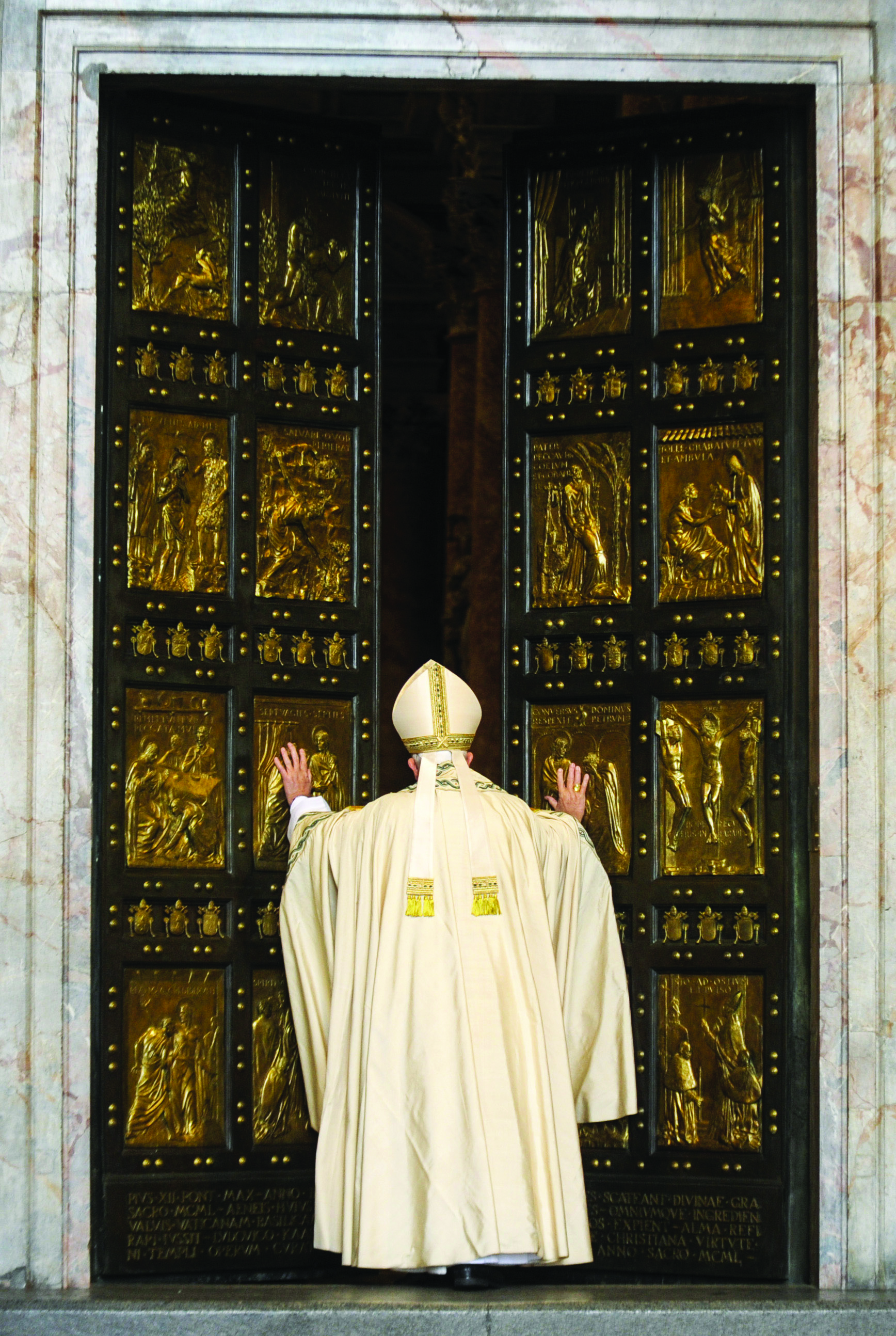

Pius XII’s motto from the beginning had been evident in his coat-of-arms, which showed the symbol of peace: a dove with an olive branch. His motto was “Peace is the fruit of justice”: “Opus justitiae pax” (Is. 34, 17). But it was precisely his willingness to mediate between the German resistance and the British government that turned this man of peace into a co-conspirator with seditious Germans, because the British had a non-negotiable pre-condition for peace talks – Hitler’s death.

Tyrannicide

Riebling’s book addresses the moral problem which both the Pope and Dietrich Bonhoeffer faced, namely, justification of tyrannicide. His book goes into the teachings of Thomas Aquinas and Jesuit theologians on this subject. Over the centuries, Catholic theology had developed a careful set of conditions under which killing a tyrant could be condoned. Tyrannicide was not justified, for instance, if it would lead to a civil war. At any rate, the Pope and Bonhoeffer, and their co-conspirators, came to the conclusion that killing a usurper of power like Hitler was justified.

Riebling reports that the Pope had sent his secretary, Fr. Robert Leiber, and others to meet Bonhoeffer and his fellow conspirators in the Swiss Alps at Christmas in 1940. (See also Eric Metaxas, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy, 2011, 374-375.)

The Pope became a supporting character in a complicated tale of inter-locking sub-plots, with a large cast of subversive Germans scheming to kill Hitler. (Indeed, the story becomes frustrating, with so many conspirators who lost their nerve at the crucial moment and so many failed assassinations — no wonder the British lost patience.)

While all this was going on below the surface, the Pope still had to maintain the appearance of neutrality. Nevertheless, quotes from Gestapo spies like Albert Hartl prove that they believed the Pope to be very hostile to Nazism. By highlighting the ways Pacelli sharpened the anti-Nazi language of the encyclical “With Burning Anxiety” (“Mit brennender sorge”), the book shows that, in the 1930s, he still could, and did, rail against Nazism.

But, as the war progressed, it became necessary that the Pope avoid polemics, in order to mediate the conflict. According to the American attaché, Tittmann, Josef Muller said that the conspirators had warned the Pope not to make public statements singling out the Nazis for condemnation, because they made the Nazis suspicious of Catholics, some of whom belonged to the resistance. Tittmann said that the Pope did not so much stay above the fray as go below it; he burrowed down below the ostensible neutrality of the Vatican and opened up new lines of communication with the German resistance — the so-called “Good Germans.”

Riebling reveals that the Pope was involved with them almost from the beginning of his papacy, and throughout the war. In fact one almost needs a chart to track all the times the Pope, through his private secretary, Fr. Leiber, and another intermediary, Ludwig Kaas, had contact with the conspirators.

Josef Müller

Riebling ties this all together into a coherent story, not mainly through the role of the Pope or the Church, but rather through that of one Bavarian Catholic layman, Josef Müller. Müller was a lawyer who knew Pacelli from before the war. He was also, among other things, a courier between the German conspirators, led by Admiral Canaris, the head of the Abwehr (Germany’s intelligence agency), and the Pope’s intermediaries.

There was one glaring exception to the Pope’s usual prudence. He had written the British conditions for peace talks on papal stationery, and sent it to Fr. Leiber. Leiber gave it to Josef Müller with the intention that Müller would just make notes from it. But Müller kept it and passed it on to the conspirators.

Later Leiber realized his mistake and asked to have it destroyed. But it was too late. In several unexpected turns of events, the Gestapo seized the document and arrested Josef Muller. When the Gestapo interrogator stupidly left Josef Müller briefly alone with that document, Müller tore it up and ate it, choking it down just as the interrogator returned to the room. Of all the German conspirators, Müller alone survived; the story of his survival rivals the script of a James Bond movie.

Church of Spies also gives more insight into the character of Pope Pius XII. In a scene in the Epilogue, the Pope and Josef Müller meet at the end and talk privately. We finally see warmth in Eugenio Pacelli. As soon as Josef enters, Pacelli hugs him. He asks how on earth Josef had survived it all. He has Josef sit down near him, so they could hold hands. Josef replies that he had relied on the prayers of his youth. At that, Pacelli squeezes his hands and says he had prayed every day for Josef – one of many moving details in this valuable and entertaining book.

NEW DATA

Riebling’s exhaustive documentation of Josef Müller’s narrow escapes, his successes, and his colorful character traits comes from a wealth of detail obtained from Müller’s own private papers and writings, from Gestapo files, and many more primary sources.

The same is true for the book’s documentation of the actions of the Pope, carried out either directly or indirectly through Fr. Leiber.

Unlike some books on Pius XII, which rely heavily on secondary sources, Riebling’s bibliography boasts mainly new, original material from primary sources. The bibliography includes interviews, debriefings, depositions, Gestapo sources, American and British intelligence sources, tape recordings, personal papers, etc. The Acknowledgements at the end highlight the depth his original research and the broad network of experts he relied on.

There is one inconvenience, unfortunately, in the presentation of all these sources: Riebling uses 72 different abbreviations to indicate these sources in the footnotes, making them a chore to reference.

SOME MISSING DATA

The Summarium

Father Peter Gumpel

Thanks to Father Peter Gumpel, Riebling had indirect access to the Vatican’s Summarium, or depositions of people who knew Pius XII. Fr. Gumpel, as the Relator, or researcher, of the life of Pius XII for the cause of his canonization, conducted those interviews. The Congregation for the Causes of Saints only makes those interviews available to the public after a candidate has been canonized; so for now, most researchers have to rely on Father Gumpel.

However, instead of giving the actual text of what Fr. Gumpel said (via tape recordings or written transcriptions of phone conversations), Riebling often paraphrases or refers obliquely to Fr. Gumpel’s words. This weakens the points he wants to make.

Some data from the Summarium is given in the second edition of Ronald Rychlak’s revised book, Hitler, the War and the Pope. Revised and Expanded, (Second Edition, Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 2010). Unfortunately, Riebling consulted only Rychlak’s first edition.

Andrea Tornielli and Sr. Pascalina

Andrea Tornielli

Sr. Pascalina

This could have been remedied somewhat if Riebling had included data from Andrea Tornielli’s book, Pio XII: Eugenio Pacelli, Un Uomo sul Trono di Pietro (Pius XII: Eugenio Pacelli, A Man on the Throne of Peter) (Mondadori: Milan, 2007), as Tornielli did have access to the Summarium.

Although Church of Spies refers to Sr. Pascalina a handful of times, it leaves out crucial passages from her autobiography His Humble Servant (St. Augustine’s Press: South Bend, IN, 2014) which would have thrown more light on Pius XII’s actions. She was the Pope’s housekeeper, nurse and adviser. By contrast, Andrea Tornielli’s book on Pius XII quotes or refers to Sr. Pascalina over 100 times. (Father Gumpel interviewed Sr. Pascalina about 20 times.)

CONVERSATIONS WITH CONSPIRATORS

Not in the Crypt

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

One misleading chapter heading is “Conversations in the Crypt.” Church of Spies contains many gratuitous references to the Vatican crypt – excavations below St. Peter’s Basilica – which have nothing to do with the story. They were probably meant to create an atmosphere of mystery but instead they create distraction. Riebling says that Josef Müller introduced Bonhoeffer to Ludwig Kaas in July (1942), and that Kaas got him interested in the Vatican excavations in the crypt below St. Peter’s Basilica. Yet he does not give any details to flesh this out.

The “Master Index” to Bonhoeffer’s complete works (Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Works, Vol. 17, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2014) never once mentions Ludwig Kaas or the Vatican crypt or the excavations there.

Deutsch says that Josef Müller, not Bonhoeffer, had conversations with Kaas. At first they met in Kaas’ Vatican apartment or in various cafes or inns, and only later, in the Vatican excavations, for greater safety (Harold C. Deutsch, The Conspiracy Against Hitler in the Twilight War, Univ. of Minnesota Press: MN, 1968, 125-126).

Conversations in the Catacombs

Josef Müller

Riebling’s book leaves a gap in the story as to what happened after Josef Müller was arrested and put in prison in April 1943. Since he was the main courier between the German conspirators and the Pope, who or what took his place?

Riebling says that Müller’s replacement was von Kessel, who was stationed at the German Embassy to the Vatican in Rome. However, Kessel’s memoir only mentions going to Germany a couple of times; as the war progressed in 1943-1944, travel and communication became mortally dangerous. But the Pope found another way to compensate for Müller’s absence.

By his ingenious use of Marconi’s new invention of the radio (even secretly bugging the Vatican rooms) the Pope proved he could be shrewd, even cunning about technology. Evidently, the Pope also found a way to move radio communications underground – to the Vatican’s Catacombs of St. Callixtus.

Riebling does not mention this, but the Pope had installed a hidden wireless in those catacombs, which were run by the Salesian Fathers. According to an eye-witness, the Salesian Superior, Father Michael Müller (no relation to Josef Müller) set up a wireless to continue communications with the German resistance. (This is recounted in Patrick Gallo, Pius XII, the Holocaust, and the Revisionists, 75, 115, notes 41 & 42 – a book Reibling references, though he inexplicably omits this piece of information.)

This was dangerous because the Germans had forbidden anyone to possess a wireless, upon pain of death. The Pope spent many hours with Fr. Müller, who wrote down messages and hid them in his socks, later to convey them to the wireless operators in the catacombs, who relayed them to Germany.

WHAT THE “GOOD GERMANS” WANTED

Even though the assassination plots failed, Church of Spies finds meaning in the aftermath, in Josef Müller’s political vision, which inspired the Christian Social Democratic party. Müller was a man of the people, standing up for the disadvantaged. In that respect, he was very different from the rest of the conspirators.

Riebling’s book includes important, revealing details about the conditions which the “Good Germans” demanded in the peace negotiations. If Count Stauffenberg’s plot had succeeded, Germany might have reverted to the old, aristocratically-ruled world he knew and desired. The old generals like Canaris would have tried to return Germany to an outdated social model ruled by an authoritarian upper class. Canaris still wanted Germany to possess Austria, and although he conceded to relinquish Poland and “non-German” Czechoslovakia, he would make no reparations.

So the “Good Germans” were just the “Somewhat Better Germans.” They would not have broken as thoroughly as necessary with the mentality of blind obedience to usurped authority. With that, the seeds might have been sown for another, future dictatorship. In fact, the conspirators did not envision an immediate return to democracy, but rather a military dictatorship for an unspecified period. No wonder the British stubbornly demanded unconditional surrender.

What neither Canaris nor the conspirators foresaw was that it would take a new mentality to rebuild Germany from scratch after the war.

CONCLUSIONS

What Church of Spies never asks is: What if God was behind all those failures to assassinate Hitler? When Hitler survived Stauffenberg’s assassination attempt, der Führer was jubilant because he thought that Providence had protected him. The conspirators thought that he had the luck of the devil. The Pope, too, thought that Hitler was possessed by the devil.

Adolf Hitler killed himself by gunshot on April 30, 1945 in his Führerbunker in Berlin

If any of the assassination plots had succeeded in killing Hitler, a whole generation of young Nazis, brainwashed in the Hitler Youth movement, might still have honored Hitler as a martyr and a hero. But by letting Hitler escape all those attempts to kill him, until he killed himself in ignominious and total defeat, Divine Providence made sure he would never be regarded as a martyr or a hero after his death. That way the deck was cleared to give Germany a fresh, new start. God writes straight with crooked lines.

Facebook Comments