By Patrick J. Deneen

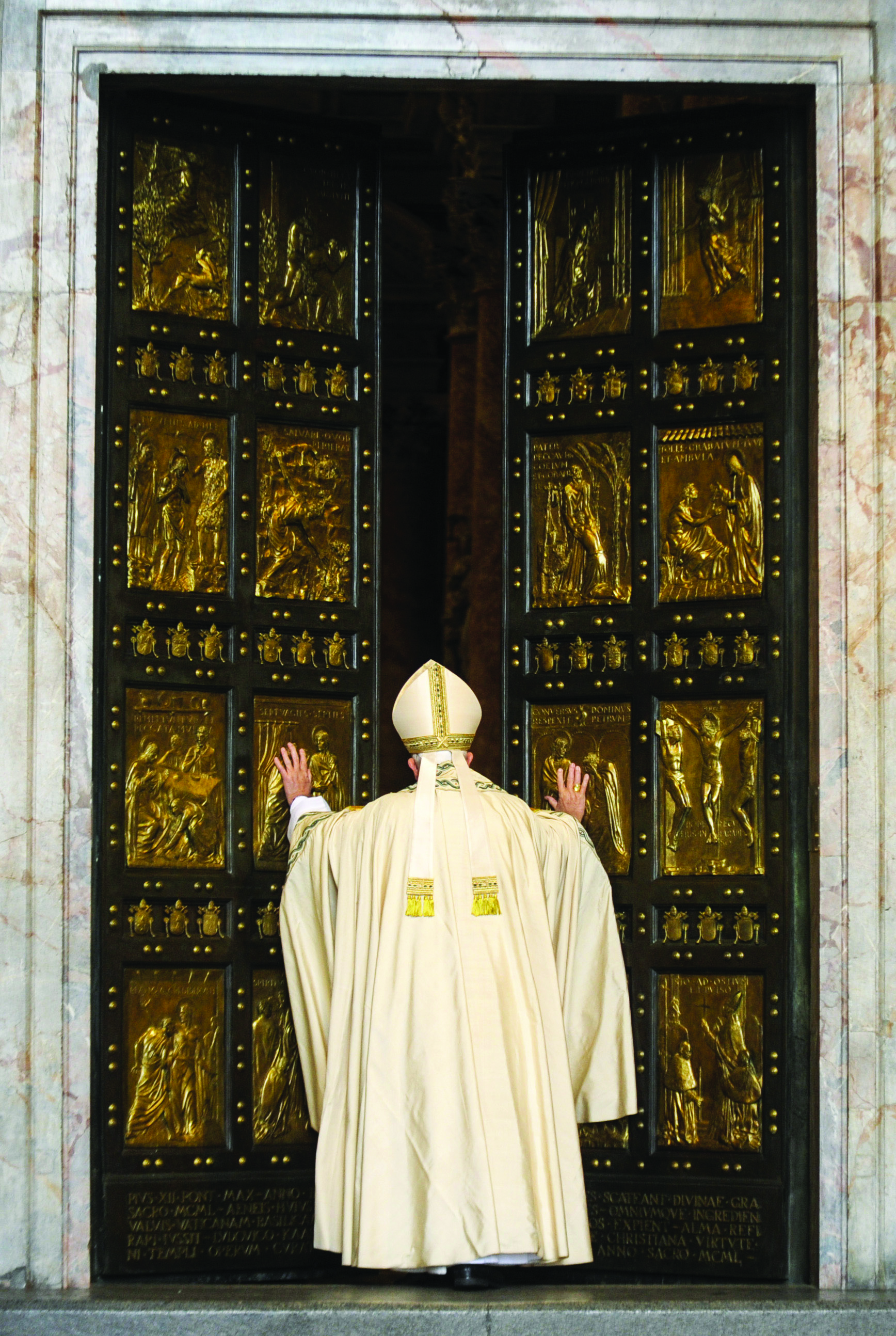

The highly-anticipated visit of Pope Francis to the United States in September comes at an extraordinary time in the history of the Church in America. There has been a certain narrative storyline about American Catholicism in which Catholics began at the periphery and ended up in the center. Just a century ago — perhaps within living memory of many of today’s Catholic grandparents — Catholics most often lived in “urban ghettos” where they were subject to frequent and sometimes vicious discrimination. Remarkably, today a majority of the members of the Supreme Court are Catholic; a Catholic serves as vice-president; and a number of Catholics are contenders for the presidency, a fact that hardly causes a murmur or notice. By many measurements, Catholics have “made it” in America.

Yet that storyline belies a real question about the future of Catholicism in America. The most recent 2015 Pew survey on American religious affiliation showed a marked drop of 3.1% in Catholic self-identification, with a dramatic drop-off of affiliation among the two younger generations born since 1981 — with only 16% of both older and younger “millennials” now identifying as Catholic, compared to 24% and 23% of preceding “Silent” and “Baby Boom” generations — while those affiliating with “None” now outnumber Catholics in the United States.

While these two phenomena might be regarded as contradictory, there is some reason to think that they are deeply connected: it seems altogether plausible that the cost of entry to “making it” in America was voluntary loss of distinctiveness, evisceration of cultural coherence, and hollowing of deeply-formative belief in which one identified first and foremost as a Catholic. Instead, liberal society’s emphasis upon toleration and the pervasive language of “multi-culturalism” and “diversity” actually has had the measurable effect of eliminating actual cultural diversity, visible in the loss of distinctive regional and religious sub-cultures for all but a few who scrupulously resist dominant forms of “popular culture.” The Catholic faith came to be regarded by many as a fungible piece of identity given that the American liberal order has the tendency of transforming all belief into “opinion” and urges citizens to adopt a stance of “non-judgmentalism” that quickly becomes indifference and even relativism. The individualism and generational discontinuity noted by Tocqueville (encouraged by American mobility) additionally attenuates transmission of tradition. Emphasis upon economic success and status further deepens the tendency toward materialism and hedonism, and renders “Churchy” subjects into weekend-only phenomena, if that.

The extraordinary enthusiasm and vast numbers of people who will doubtless greet Pope Francis will thus mask what is a deeply troubling time for Catholicism in America, which increasingly looks to resemble Europe in its path toward secularity and religious disaffiliation.

Going forward, the future looks challenging and even grim for the Church. Not only does the trend of declining numbers look daunting (and while immigration of Hispanics may stem some of that bleeding, other measures show substantial drop-off among the second generation as well), but the Church’s social and political position is also under significant duress. While its continued stance against abortion has remarkably appeared to persuade a growing number of fellow citizens, the ongoing stain of the scandal in the clergy and its more prominent stand against contraception (prompted by the promulgation of the HHS mandate) have led many to dismissals that resemble 19th-century hostility. But it is above all the Church’s opposition to same-sex marriage, and the likely implications of that stance for the religious liberty and tax-exempt status of its institutions, that is most worrying.

But perhaps it is the increasingly evident hostility of a broader secular culture that will be the ironic source of revival of the Church in America, and potentially, new fuel to conversion of what is so evidently an increasingly harsh economic, dismal familial, and degraded cultural landscape. Just as the apparent success of Catholics has masked a deeper rot, so too perhaps the evident hostility of the culture to the Church will be the opportunity to awaken, deepen, and rouse a more evangelical, loving, open, committed faith that will — like the exemplars and martyrs of the early Church — inspire wonder and invite imitation.

Just as the success of American Catholics may be no real cause for celebration, so too its likely marginalization may be no reason for begrudging lamentation.

As Pope Francis rightly stated in Evangelium Gaudium, “An evangelizer must never look like someone who has just come back from a funeral.”

Or, we might slightly alter the words of Mark Twain in hoping that “the reports of Catholicism’s death are greatly exaggerated” — if Catholics will be Catholic, and be willing to entertain the possibility of being a little less “at home,” a little less striving, above all, to “make it” in America.

Facebook Comments