The exhibition “Constantine A.D. 313: The Edict of Milan and the Age of Tolerance” commemorates the 1700th anniversary of this proclamation issued jointly by Emperors Constantine and Licinius in February 313 A.D. at Mediolanum (today’s Milan), then one of the Roman Empire’s four capital cities (the others being Nicomedia, Trier, and Sirmium). Milan was the seat of the Western Augustus in the four-emperor system of government known as the Tetrarchy established by Diocletian in 293 A.D.

Thanks to his victory over Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in Rome on October 28, 312 A.D., immediately after which he converted to Christianity, Constantine had become the new Western Augustus. Consequently, in Milan’s magnificent imperial palace, he met his round-faced Dacian colleague, Licinius, the Eastern Augustus since 308 A.D., to divide the Roman world between them and to consolidate their alliance by celebrating Licinius’ marriage to Constantine’s half-sister, Flavia Julia Constantia. However, within a year the brothers-in-law’s relationship had soured. The cause was probably political ambition: Licinius, a pagan, had tolerated the Edict’s “ecumenism,” while Constantine, already a committed Christian, tolerated paganism and other religions, but actively promoted Christianity and successfully slandered his counterpart. The next decade was a seesaw of battles and uneasy truces between the two until Constantine finally prevailed militarily and had Licinius executed by hanging in 324 A.D.

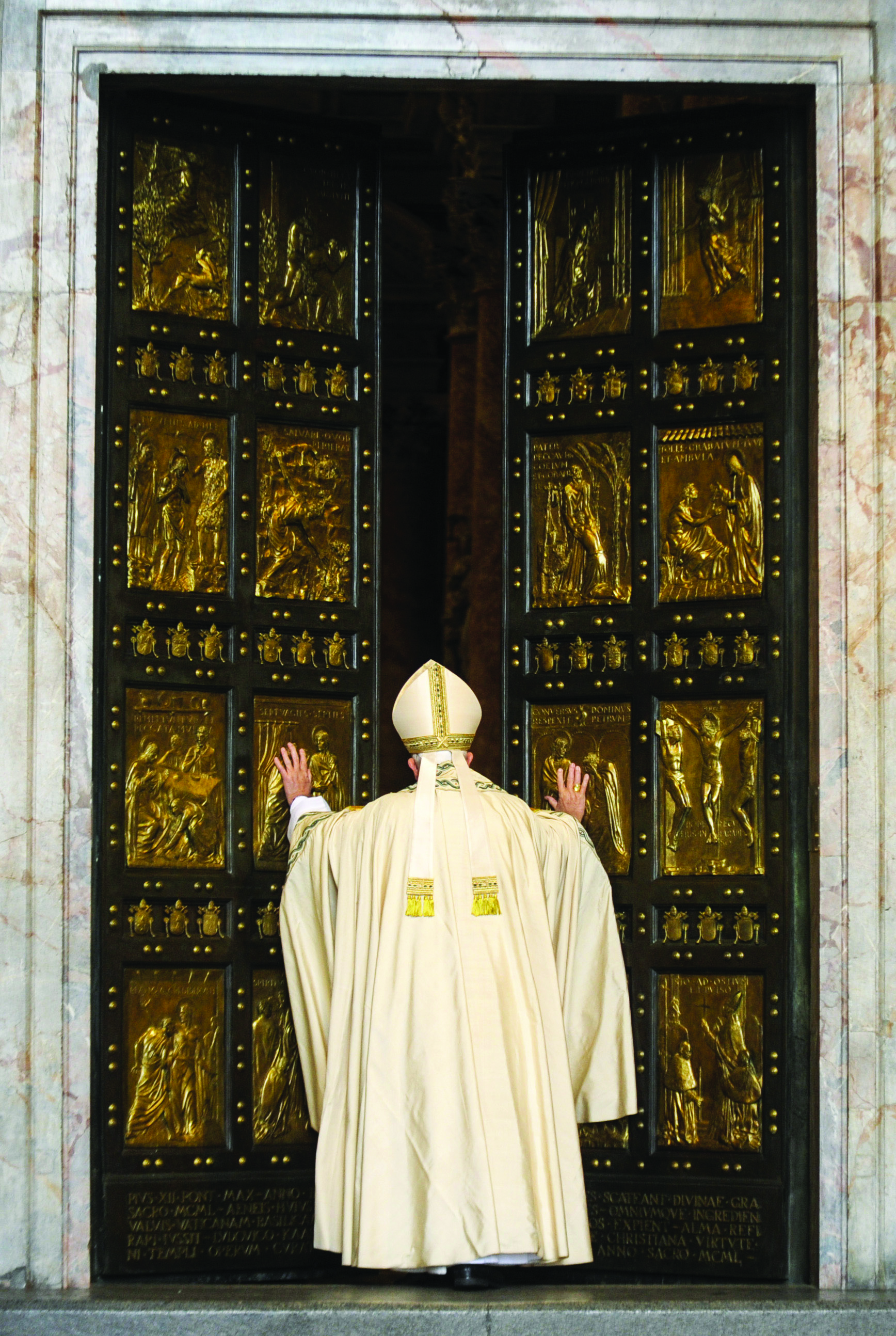

Nonetheless, at their first meeting 11 years earlier in Milan, together the brothers-in-law had changed world history. They had ordered functionaries in outlying parts of the empire to enforce the decree issued by Emperor Galerius at Salonica in 311 A.D., which for the first time had granted Christianity the status of a legitimate religion. Immediately afterwards they had also issued further instructions, their Edict of Milan, to grant all persons throughout the empire the right to worship whatever deity they pleased, assure Christians of their legal rights (including the right to organize churches and the exemption of Christian clergy from municipal civic duties), and direct the prompt return to Christians of their confiscated property.

This Edict, handed down to us in two different versions, one in Lactantius’ De Mortibus Persecutorum (On the Deaths of Persecutors) and the other in Eusebius of Caesarea’s History of the Church, an exhibition wall panel explains side-by-side in Italian and English, “was a watershed moment, which lies at the roots of the Christian cultural heritage of Europe and the world. It also ratified the novel concepts of tolerance, religious freedom and openness to new forces, such as Christianity, able to revitalize the empire. Further, it proclaimed a new respect for the individual and his or her freedom.” In short, it aimed to guarantee peace and prosperity for the empire under divine protection.

On until September 15 in the Colosseum and Curia Iulia after five months in Milan’s Palazzo Reale, the exhibition is divided into six sections: (1) Milan: An Imperial City; (2) From Christian Persecutions to Constantine’s Victory; (3) The Krismon as a Symbol of Faith; (4) The Age of Tolerance: The Survival of Paganism and the Search for a Single God; (5) The Protagonists of the Constantinian Period: The Army, Church and Court; and (6) Helena: Empress and Saint, which highlights the singularity of Constantine’s mother within the imperial court and the history of the Catholic Church. Over 200 archeological artifacts and artworks are on display. Among the highlights are a ring with the Krismon on loan from Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum; a rare 5th-century fragment of cloth, probably part of a pall, embroidered with the Krismon, from London’s Victoria & Albert Museum; the Capitoline Museums’ famous statue of Helena, which left Rome for the first time when it went to Milan last October; a hexagonal gold pendant with a coin of Constantine and small busts in relief, from the British Museum; and the priceless 4th-century cameo believed to represent the triumph of Licinius but probably depicting the triumphant Constantine instead, from the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

Among the Renaissance paintings inspired by the legend of Helena and her discovery of the True Cross at Jerusalem is Cima da Conegliano’s St. Helena, on loan from the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Another is Veronese’s St. Helena’s Vision, one of numerous artifacts; rings, lamps and sarcophagi with the Krismon; statues of a lion-headed pagan demon and other pagan deities; Jewish and Christian epitaphs; and statuettes of the Good Shepherd, from the Vatican Museums.

Although what remains of late antique Mediolanum doesn’t allow us to reconstruct the imperial city accurately because its buildings were razed to the ground on various occasions over the centuries, we know that its architectural layout, as in Roman Trier, was a military encampment grid. There are remains of an imperial palace housing the emperor’s residence and administrative offices, grandiose public baths, a Roman villa transformed into a church, and a pagan necropolis turned Christian cemetery. Most importantly, another wall panel tells us: “In the Constantinian period the city’s religious center moved to the place where the roads leading east and west crossed, which later became Piazza del Duomo… The first phase of the bishop’s complex dates to this time…The remains of a baptistery, known as Santo Stefano alle Fonti, have been identified beneath the north sacristy of the current cathedral.”

After a virtual tour around imperial Milan thanks to both finds, recent and not, as well as reconstructions, a substantial part of the exhibition is devoted to Constantine’s political and religious revolution, which for the most part soon put an end to the persecution of Christians, although on display are a graffito, a fresco, and a sculpted column showing Christian martyrdoms.

In contrast, also on display are numerous examples of the Krismon, a graphic symbol chosen by Constantine to express his adherence to Christianity. Formed by superimposing the first two Greek letters of the word “Christ”: X (Chi) and P (Rho), it’s said to have been the emblem on the labarum or standard Constantine’s troops carried into the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Thus repeatedly reproduced on rings, pendants and other gems, household decorations and utensils such as cups, dishes, drapes and terracotta and bronze lamps, liturgical objects such as large bronze lamps, and funerary monuments, it became the most important symbol of the Christian faith.

The section on religious tolerance is illustrated by the persistence of several religions in the Empire of Constantine and his successors throughout the 4th century, with the use of both Christian and pagan iconographies on artworks destined for official and private use, such as the marble relief of Iupiter Dolichenus and Other Deities, the marble statue of Isis Fortuna, and the marble statue of Heracles, all from Rome’s Capitoline Museums, and the several magical gems from the Museumslandschaft Hessen in Kassel.

“At the same time,” a wall panel reports, “a tendency to seek a single god emerged, evidenced by the establishment, especially in military circles, of the cult of Sol Invictus, of Mithras with whom he soon became associated, and the popularity of monotheistic Judaism, more suited to meeting the needs of worshippers. Serious restrictions on paganism were only introduced by Theodosius in the late 4th century when it was officially banned.” Hence on display here are reliefs of Mithras, reliefs showing the menorah, statuettes of the Good Shepherd, and coins, gems and glass depicting Him.

The next section carefully considers the three institutions which played a leading role during Constantine’s reign as the sole Roman emperor (325-337 A.D.): the army to which Constantine made sweeping organizational changes, the expanding Church, and the wealthy imperial court.

With Constantine’s support the Church gained in authority. New churches were built in cities which hosted the Court: Milan, Trier, Rome, and Aquileia, founded in 313 A.D. immediately after Constantine’s conversion and a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1998. A wall panel tells us: “Members of the court were also ‘church builders.’ Princess Anastasia, Constantine’s half-sister, built a chapel in the imperial palace on Rome’s Palatine hill where the first Christmas Mass seems to have been held in 326 A.D.”

Another “church builder” was Constantine’s mother. Although his father, Constantius Chlorus, either never married or divorced Helena, when Constantine came to power he bestowed extraordinary honors on his mother, including the title of Nobilissima Foemina and later Augusta, the highest title to which a woman could aspire. Of enormous importance for the spread of Christianity, she is credited by her biographer, Eusebius of Caesarea, with discovery of the True Cross and other priceless relics such as the Holy Nails and Our Savior’s seamless cloak, the Robe, revered in Trier since the Middle Ages. Thus appropriately the patron saint of archeologists and the subject, together with the triumph of the cross, of the exhibition’s final section, soon after her return from the Holy Land, Helena died in Rome around 328 A.D. Her relics are venerated in the Roman church of the Aracoeli; her sarcophagus is displayed in the Pio-Clementine Vatican Museum.

Facebook Comments