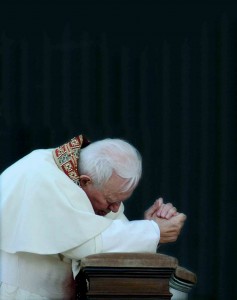

“Let me go to the House of the Father”… These were the last words of Blessed Pope John Paul II before he lapsed into a coma that ended in his departure from this world on April 2, 2005. His final pronouncement to the world, uttered in near silence to a religious sister tending to his bedside care, leaves us with the richest legacy concerning what the beloved Pontiff held dear to his heart, the Heart of our Lord.

Elected on the liturgical feast of St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, Apostle of the Sacred Heart, on October 16, 1978, Pope John Paul II said and wrote more on the Heart of Jesus than any other Pope until his day. His treasured invocation from his favorite prayer, the Litany of the Sacred Heart, “Heart of Jesus, fountain of life and holiness,” is unsurprising given his devoted love for Divine Mercy. Blessed John Paul II was born into eternal life on the Vigil of the Feast of Divine Mercy….

As he always believed, God’s timing is never accidental, and his life testified to this truth. Reflecting on this image of the Divine Mercy, the rays of which emanate from the Sacred Heart of Jesus, it should come as no surprise to us that Blessed John Paul II is both a Pope of Divine Mercy but also an important Pope of the Sacred Heart, one who strove always to reflect in his own life the Incarnate Love of the Father, Jesus the Son.

Upon the piercing of the Heart of Jesus at the Crucifixion, the Church is born in nuptial union with Christ her Lord. Mary, at the foot of the Cross as the pre-eminent icon of the Church as Mother, receives the blood issuing forth from her Son in His perfect gift of self. In communion with Mary, we enter into the Heart of Jesus and find our home in interpersonal communion also with God the Father and God the Holy Spirit, in the place where the Trinity dwells among the Mother of God and the Communion of Saints (Catecheses (Cat.) 68:3-4, 71:5).

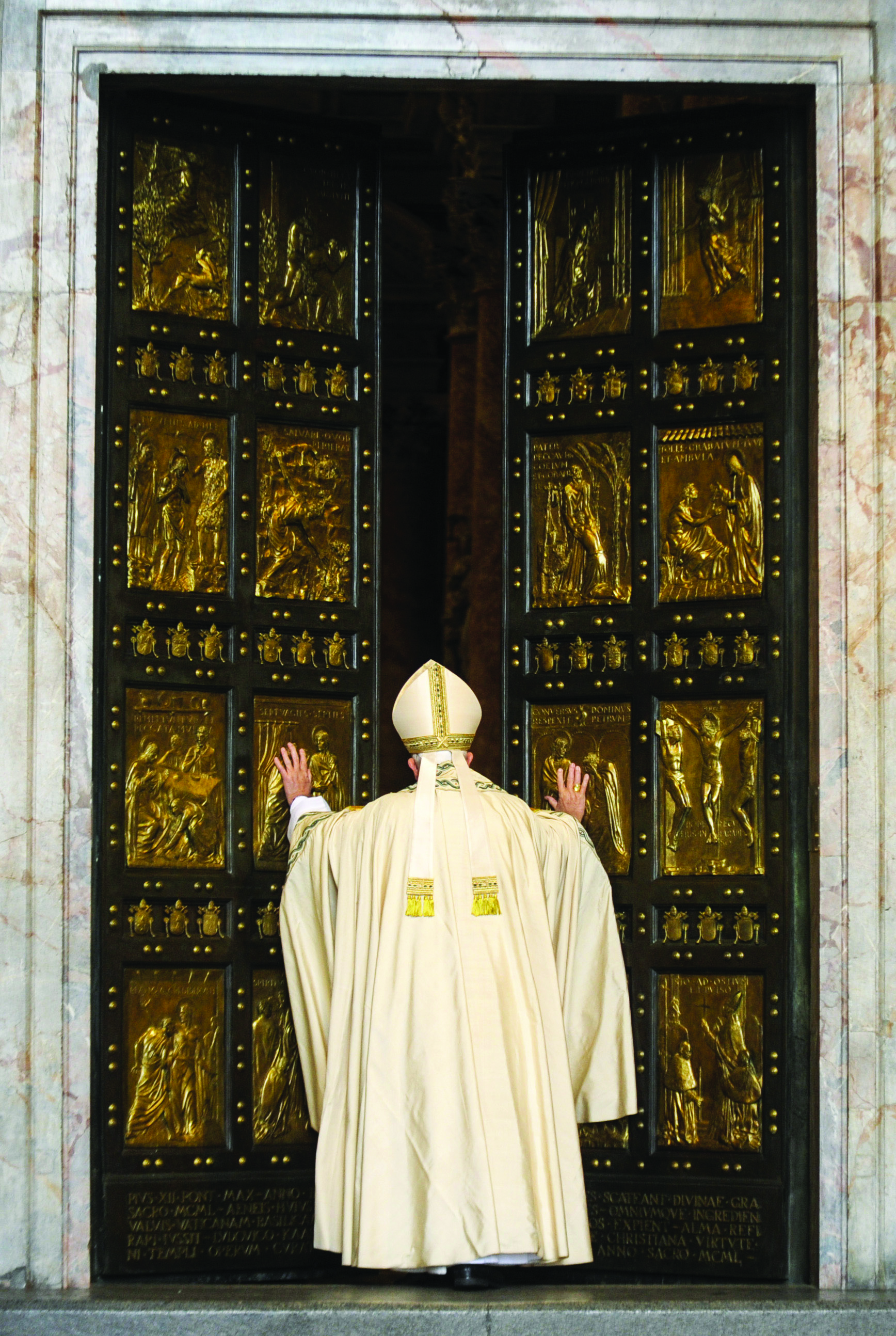

Blessed John Paul II always sought during his life to follow along the footsteps of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, and she was the star who guided his path, lighting his way to the Heart of Jesus. Certainly, the Holy Father’s heart longed at the moment of his passing to be in heaven, in perfect interpersonal communion with the Heavenly Father, an encounter made possible first through his communion with Christ the Son and our Blessed Mother, in the spirit of Totus Tuus, where the hearts of Jesus and Mary are inseparably united in loving interpersonal communion. He clearly understood God the Father as rich in Divine Mercy (cf. Dives in misericordia, his encyclical on God the Father), thirsting in his last moments to enter the heavenly house where Divine Mercy eternally finds a dwelling place. Considering this encyclical was written in spiritual preparation for the great hinge of his Pontificate, the Great Jubilee of 2000 (St. Faustina Kowalska, Apostle of the Divine Mercy, in fact was the first saint canonized in the new millenium of our Faith), alongside his general audiences in 1999 on God the Father, we understand the Heart of Jesus more profoundly as the house of Divine Mercy, the font from which the Father’s Divine Mercy springs forth.

In his theology on the Sacred Heart, which according to Pope Pius XI (cf. Miserentissimus Redemptor) and Pope Pius XII (cf. Haurietis Aquas) is a summary of the entire mystery of redemption, Blessed John Paul II further deepens a tradition already well articulated by his predecessors. In his letter to the Jesuit superior general upon his visit to Paray-le-Monial on October 5, 1986, Pope John Paul II proclaimed, “In the Heart of Christ the human heart comes to know the true and only meaning of life and destiny, to understand the value of an authentically Christian life, to protect itself from certain perversions, to unite filial love for God with love for neighbor. In this way – and this is the true meaning of the reparation demanded by the Heart of the Savior – on the ruins accumulated through hatred and violence can be built the civilization of love so greatly desired, the kingdom of the Heart of Christ.”

It is crucial to understand the connection between Blessed John Paul II’s comment here and what is articulated by the Second Vatican Council in Gaudium et Spes 22 on man’s search to be conformed to the likeness of Christ, who “loved with a human heart”: “Pressing upon the Christian to be sure, are the need and the duty to battle against evil through manifold tribulations and even to suffer death. But, linked with the paschal mystery and patterned on the dying Christ, he will hasten forward to resurrection in the strength which comes from hope.”

We would serve Blessed John Paul II’s legacy honorably by deepening our understanding of his Catecheses on Human Love through the lens of the theology of the heart, where the Law of the Gift (Cat. 13:2 and 16:1, cf. Gaudium et Spes 24:3) is written integrally into the human heart (Cat. 16:3). When we approach his teaching as a call for man’s heart to enter into perfect communion with the Heart of Jesus, we come to understand more profoundly the role of suffering in this great treatise on human love in the divine plan, a theology that he himself admitted had not yet reflected fully upon the “problem of suffering and death” (Cat. 133:1).

Blessed John Paul II’s last months of earthly suffering certainly provide a noteworthy reflection on the theme, in how the late Pope sought daily to unite his sufferings and find their meaning within the suffering Christ. He thus sought to live out — through the daily trials of his own body — the meaning of his apostolic letter on suffering, Salvifici doloris (SD), in which the Pope articulates that to understand the “salvific meaning of suffering” (2), we must remember that “the Redemption was accomplished through the Cross of Christ, that is, through his suffering” (3, emphases in original).

It is in light of the salvific meaning of suffering that we do well to ponder the Heart of Jesus in perfectly spousal, virginal union with the pure, chaste Heart of Mary, icon of the Church that is the Body of Christ, whose flesh is the hinge of our salvation. Their hearts are hearts of love, and as such, they are hearts pierced deeply by human suffering.

The task of uniting the theology of suffering with the theology of the body, which Blessed John Paul II specifically identified as necessary in Catechesis 133, has yet to be taken up adequately by popularizers of the “Theology of the Body.”

Christopher West, in his new book At the Heart of the Gospel: Reclaiming the Body for the New Evangelization, mentions suffering at times but falls significantly short of integrating the theology of suffering with the role of the body in Christ’s redemption of man.1 In the book’s second chapter, “The Wound of Puritanism,” West suggests that the world hurts from Puritanism’s prudish treatment of sex and disparagement of the human body, stating that the answer to this problem involves a “careful and respectful ‘lifting of the veil’ [of the body] in order to correct a puritanical mentality” (p. 46), even to “enter behind the veil” (p. 47).

However, the Scripture passages upon which West relies to justify his “unveiling of the body” (Ex. 26, 2 Cor. 3, Mk. 15, Heb. 6 and 10) do not refer to the body as concerns sexuality. Rather, these passages are best understood through the ultimate sacrifice by Jesus of His Body and Blood on the Cross for our redemption.

Through the theology of the heart, we encounter in these passages a foreshadowing of the icon of the Sacred Heart, the heart of the Son of Man that has been sacrificed willingly by our Redeemer up to death and torn by the soldier’s lance. Through the perfect suffering of the Son, God allows the veil of the Holy of Holies — the Heart of Jesus — to be opened, revealing to the world the “seat of mercy” that rests upon God’s “ark of testimony” found within (Ex. 26:34).

While West asserts that the “fundamental sign through which God communicates himself to us is the human body” (p. 59), the supreme manifestation of such communication is not through sexual intercourse, even when it transpires in a pure, spousal union. Ultimately, the theology of suffering provides the hermeneutic key to understanding God’s love as expressed through the human body: Jesus has suffered and died on the Cross to redeem man, through a perfect manifestation of the Law of the Gift… “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (Jn. 15:13).

The strongest friendship in the communion of persons is founded upon the body’s perfect gift of self in sacrifice, not merely through a deeper understanding of the body, per se, or of its sexual union. It is in the heart, not simply in the body, that we are led most intimately to the heart of the Gospel and are given the ability in purity to see God (Mt. 5:8, cf. West p. 73).

To be fair, West does mention the importance of self-renunciation in combating lust. However, his failure to integrate the theology of suffering throughout his portrayal of a redeemed sexuality establishes a model for Christian sexuality that risks idolizing and impurifying the very body he seeks to portray as an icon of God’s love.

The integration of the Church’s theology of suffering in the Heart of Jesus, in light of Blessed John Paul II’s Catecheses, provides the greatest opportunity for us to enter into the “‘great mystery’ of Christ’s love for the Church” (West, p. 217) and to understand the fullest meaning that God has given to the human body.

As his life drew to a close, Blessed John Paul II’s suffering heart proclaimed the beloved pontiff’s final teachings to the world, in a letter written not by human hands but by a human heart that testified to his final months of suffering on earth. In an abundant outpouring of love for God, the Blessed Mother of God, and the Church, Blessed John Paul II pronounced this message word for word in his final days in contemplated silence, depending intimately on Divine Mercy emanating from the Heart of Jesus. Having done so, he now experiences in fullness an encounter with God the Father, “gazing with unveiled face on the glory of the Lord … being transformed into the same image from glory from glory” (2 Cor. 3:18).

A complete essay by Fr. Gresko on Christopher West’s new book, At the Heart of the Gospel: Reclaiming the Body for the New Evangelization, may be referenced by clicking here.

Facebook Comments