“Christ the Consoler” by Danish painter Carl Bloch (1834-1890).

The great British Catholic writer G.K. Chesterton once wrote: “It is a paradox of history that each generation is converted by the saint who contradicts it most.” In other words, the message that we most need is often the one we least want to hear. This is no doubt the case with our present pontiff, Pope Francis.

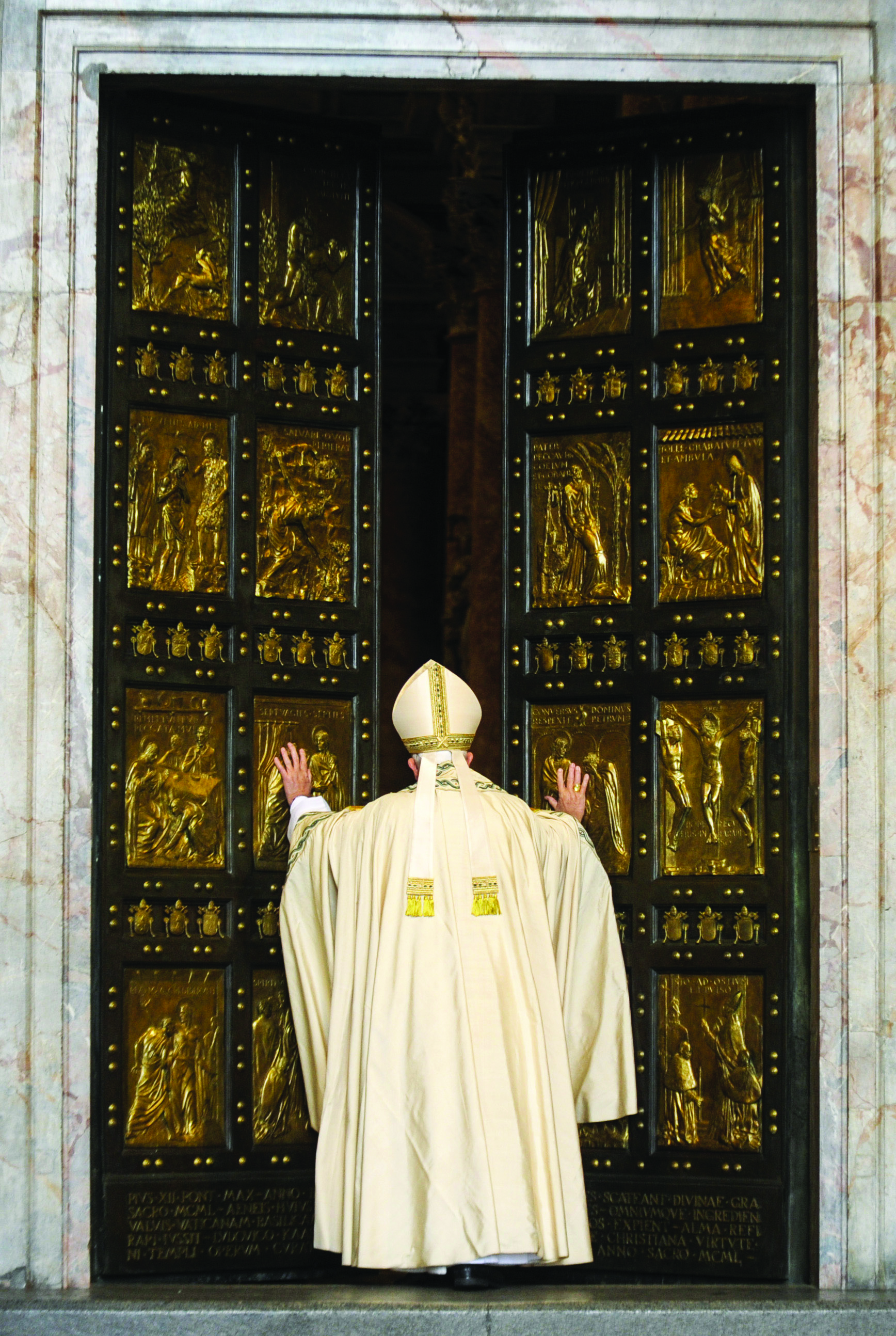

Pockets of orthodox Catholics the world over are finding it hard to warm up to Francis. Some lament that he is unaware of the effect that his words and gestures have, and deplore how easily they are twisted to promote agendas contrary to Church teaching. Others find him less than careful in his expressions, leading to possible doctrinal confusion among believers and unbelievers alike. There is much hand-wringing and sighing among still others who envision the Church losing precious ground in the culture wars that rage around us. Yet as much as we may think we know better, it may just be that God gave us this Pope at this moment for a reason. Francis may just be the Pope we need right now. In the book of Revelation, Saint John repeats over and over an exhortation that is useful to every new generation of Christians: “Let anyone who has an ear listen to what the Spirit is saying to the churches.” As always, the Spirit is saying something now, if we are willing to listen. God is ever at work, and the task of believers is to discern this work and unite with it, rather than wishing He would conform Himself to our programs. God does not like being put into a box, or, as C.S. Lewis would say, He is not a “tame lion.”

Throughout the more than 30-year span that embraced the pontificates of Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI, we lived in a glorious period of doctrinal clarity. After the confusion that blanketed the Church in the years immediately following the Council, we were graced with a continuous flow of teaching that clarified and reaffirmed Church doctrine on everything from the Real Presence of Jesus in the Eucharist to the evils of abortion and euthanasia to myriad other issues such as stem cell research, liberation theology, contraception, the male-only priesthood and the uniqueness of salvation in Christ. If anyone still has doubts regarding what the Church teaches on these and many other matters, well, that person simply hasn’t been listening.

So what of Francis? He hasn’t made doctrinal definitions the core of his pontificate. Looking at his words and actions, I believe we can discern a different approach, one that may strike us as novel but

really takes us back to our beginnings as a Church. It would seem that Francis simply looked to the Gospel, to the life of Jesus Christ, and decided to pattern his pontificate on the public life of Jesus.

Jesus said that he had come to preach good news to the poor, and continually reached out to the needy and disenfranchised, much to the chagrin of the religious establishment of his times. The Pharisees were up in arms because he “welcomes sinners and eats with them” (Lk 15:2). Jesus was hard—even harsh—with the self-righteous, but remarkably indulgent with “tax collectors and sinners.” He commanded us not to judge, and claimed that he had come to call sinners, since the healthy don’t need a physician. The professionally religious class found Jesus irritating and problematic, while those who lived on the margins of Jewish observance found themselves welcomed and embraced.

Francis’ approach is similar. To take just one example, we could cite his celebrated line “Who am I to judge?” when speaking about homosexuals struggling to live a good life. This was not a change in doctrine but a change in emphasis. Francis could have reaffirmed the Church’s teaching on homosexual acts, but he chose to focus on the person. Compare this to the scene where an adulterous woman was brought before Jesus. He could have reiterated the Mosaic teaching on adultery. Instead he chose to invite those without sin to begin throwing stones and told the woman that he did not condemn her.

Jesus told parable after parable about the need for mercy. Sinners usually knew they were sinners and in any case had

plenty of people to remind them of their faults. Jesus saw no need to hammer this point home any further. Instead he went out in search of them, like the good shepherd who leaves the ninety-nine sheep in the wilderness in order to bring back the lone stray.

Undoubtedly, the ninety-nine “good sheep” would have felt abandoned, even unfairly treated, as their shepherd went searching for the sheep who was lost, probably through no one’s fault but his own.

To add insult to injury, Jesus proclaimed that there was more joy in heaven over one of these lost ones coming home than over the ninety-nine who never strayed. Like the elder brother in the parable of the Prodigal Son, the professionally pious of Jesus’ time could not share in the joy of their returning brethren.

Pope Francis shakes us up. This is a good thing. He asks us whether we are doing all we can to reach out to those around us who are in need, and we squirm uncomfortably, knowing that we are not. We would like to sit back knowing we have our doctrinal ducks in a row, thanking God that we are “not like other people: thieves, rogues and adulterers” (Lk 18:11). But Francis is telling us to look around and look within. He is asking us to be more merciful, more understanding, less sure of ourselves and less complacent.

He is reminding us that God is always issuing an invitation to all of us—older brothers and younger—to draw nearer to himself, if we can just accept it.

Thomas D. Williams, Ph.D., is a theologian and author of A Heart Like His: Meditations on the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

Facebook Comments