Here we are at Christmas—a time of joy in the East, in the West and for Catholics and Orthodox alike. In this special Christmas issue, we focus on the aspect of prayer and silence in awe over the coming into our world of Christ, the Savior. And we have a special section on the Romanian Greek Catholic Church. In order to make this all visible, beyond words, we publish images of three beautiful Christmas icons from the Christmas tradition of the East. The following text explains the meaning of these icons, during this 2014 Christmas season.

The icon of the Nativity is arguably the richest pattern in all iconography. Every detail is packed with theological information and spiritual insight. Indeed, it is safe to say that a veritable encyclopedia of theology could be written using only this icon as a source! Full justice to the subject is not possible in just a short article, but it is instructive to cover the high points at least.

First, a general note about icons and their place in Eastern theology is in order. St. John Chrysostom, when asked how to go about teaching non-believers about the Faith, replied, “Take them to the Temple and show them the Holy Images.” This is a succinct summary of the place icons hold for the East: they are theology that can be shown and exhibited, so that those who are ignorant or illiterate might have access to Scripture and tradition. They form a direct connection between heaven and earth. Many volumes have been written on this subject; suffice it to mention St. Basil the Great’s dictum that “the veneration given to an icon passes to its subject.” This is not said of Western art, for reasons too complex to discuss here. “Doing theology” with icons is a rewarding spiritual exercise once one gets the hang of it. The following hopefully will give some indication how this is done for those just developing a familiarity with these treasures of the Church.

Chronologically, the Nativity icon starts at the very beginning. The material universe is called into being by the Creator and promptly suffers grave loss in the great fall of Adam. Human moral damage is horrendous, of course, but the harm is not limited to humanity. The icon depicts a stark desert scene, fractured and desolate. The sharp jagged edges of the rocks indicate that the entire universe is in agony, awaiting the Savior Who will smooth and level every mountain and fill every valley. That the Redeemer has now arrived and regeneration has begun is evidenced by the new growth of vegetation appearing here and there in the crevices.

The animal world is represented by the ox, the donkey and mostly by the sheep. In the lower right corner, a group of sheep drink from a new spring, mysteriously flowing in the midst of the desert. Beasts share in the re-creation of the universe, just as do the mineral and vegetable realms. There is more to the sheep, of course. In His teachings, Jesus constantly referred to His people as sheep in need of the Good Shepherd; the icon recalls the scene at the well where the promise of living water is made. The spring flowing from the coming of the Messiah is such that those refreshed by it will never thirst again.

Throughout the Old Testament, God kept the promise of a new creation alive through the words of the prophets.

Prophecy is represented in the icon with the shepherd playing music next to a tree. The Jesse tree is symbolic of the kingly origin of Christ, Who is foretold to come of the lineage of King David, son of Jesse. King David was a musician; here we see the young shepherd David rejoicing at the fulfillment of the prophecy of the Messiah. The root of Jesse, through King David and so to Jesus, has now grown into a full tree.

Jesus is the greatest fruit of that tree.

More proximate to the actual time of the Nativity, we see Joseph seated near the bottom of the icon, conversing with an ominous black-clad figure. Joseph was perplexed by the events swirling around him. Even less than Mary did he understand how this birth came about. The devil always takes advantage of confusion, and so we see a demon tempting Joseph to simply give up on the situation, put Mary away and go back to his uncomplicated existence as an obscure carpenter. On the other side of the equation, God saw to it that Joseph was given enough understanding that he decided to stay the course with Mary and Jesus. He was still confused; no one fully understands God’s mysterious ways with humanity, and Joseph was no exception. But, despite his doubts, Joseph stayed in the picture and thus earned his place in the icon. Everyone must take their cue from Joseph; no matter what problems may arise in accepting God’s ways and means, all are yet called also to remain in relationship with Jesus.

In the right of the icon, an angel is announcing the good news to a shepherd. The body of the shepherd is distorted; his upper body seems twisted, as do more obviously his legs. Here we see a representation of fallen humanity. All are twisted and distorted due to the fall. In iconography, a figure seen from the rear or in profile is likely to indicate a problem with that figure. The shepherd, however, is seen in the very act of turning around, to present his face to the viewer. As has been seen with the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, the coming of Christ has a profound effect on human beings. The sickness and distortion of the soul can now be overcome with God’s gracious act of becoming man. He has given us the means to turn our lives around and be healed of all the distress caused by the fall. Significantly, the angel blesses with the Byzantine hand configuration which spells out ICXC, the Greek abbreviation for the name of Jesus Christ.

Two groups of angels are depicted in the icon. One group stands with uplifted hands in prayer and awe at the miraculous events unfolding. The second group is bowing in adoration before the Incarnate God. The three in the front of this group stand as if offering themselves to Jesus, but their hands are empty. They recognize that with this unique intermingling of God and man, their status in the heavenly realm is changed. God did not choose to unite Himself to angelic nature; in recognition of this fact, the angels humbly offer their humility and emptiness to the God-Man.

The Magi enter the scene from the left of the icon. Their ages are a clue as to their significance. They range from youth to old age, an indication that salvation is offered to all, regardless of age or station in life. But notice that the elderly figure is first in the line, while the youth is last. Here lies a paradox of the spiritual life. Human beings are born in a miserable fallen state, fated eventually to weaken, age, sicken and die. Physically, we can expect decay and ruin. So there is a progression from the youth to the eldest of the Magi. Spiritually, the process is reversed. We are born with our souls elderly, tired, spent and steeped in ruin. With our entrance into the life of Christ, our Baptism, the process and state of ruin turns around. As we age physically and progress in spiritual life, our souls should grow ever more youthful, vibrant, healthy and strong. An elderly Christian should be rather far along in the process of human spiritual regeneration. Theosis or becoming like unto Christ is the entire point of life, after all, and a life well-spent results in a real family resemblance!

The midwives in the bottom left corner speak further of Baptism. The washing of the Infant indicates the true humanity of Christ; birth is generally a messy affair and Jesus too needed some immediate post-natal care. But, the vessel they are using for the washing is a Baptismal font! The scene looks toward the Baptism by John in the Jordan as well as the Baptism of individuals by the ministers of the Church. The theology of water for ancient Israel is a complex subject. The pertinent thought in terms of the icon concerns the use of water to destroy sin. The two events most prominent in Israel’s history for this purpose are the great flood of Noah and the destruction of the Egyptians in the Red Sea. In both cases, water swallows sin and becomes impregnated with it. In descending into the waters of the Jordan, Christ, according to Gregory of Nyssa, “descends into the filth.” When the sinless One is submerged in the waters, a remarkable thing happens: the sinless Christ takes on the sin held in the water and in the process adds a new purpose to the waters of Baptism. Besides the destruction of sin in individual souls, the waters also begin the process of human spiritual regeneration. Christ takes on the role of the scapegoat in Israelite ritual and will be slain, like the poor goat, for the remission of sins. There is obviously much more to be said of Baptism and water, but the important point is simply that the midwives represent Holy Mother Church administering sacraments and grace-filled regeneration to her children.

What mother does not gaze adoringly at her newborn infant? Yet, here we find Mary gazing directly at us, not at Jesus. This is a common element in iconography; very briefly, the theology involved simply indicates that she is fully aware that her Son is not destined for a normal family life in Israel, but rather that He is freely given by her for the sake of the world. Her gaze at us echoes her words at the wedding at Cana: “Do whatever He tells you.” From her own submissive act agreeing to Gabriel’s message, this is her constant refrain; she herself shows us the shape of perfect obedience.

At the center of the icon lies the figure of Jesus Christ Himself, the focus of the entire work. He is wrapped in cloths, swaddling clothes according to Scripture, but they are a burial shroud in the icon. The manger itself is a sepulcher. He lies in the darkness of a cave, prefiguring His own tomb. There is a lesson here regarding the sacred character of human life. Jesus emerges from the womb of Mary into the tomb of the cave. He later emerges from His own tomb after the Crucifixion. An important connection is thus drawn: each human birth becomes a symbol of the Resurrection. Any interference with the natural progress of life is a betrayal of the Resurrection.

Jesus lies in a manger, a food trough for beasts. Already it is clear that He is intended to be consumed by His own special beasts, spiritually starving human beings. There is another presentiment of that notion with a sheep to the right of the cave nibbling upon the Tree of Jesse, in fact.

The final element in the icon consists of a dark ray descending from heaven to the scene in the cave. The darkness makes it clear that human understanding does not extend to all the mysterious doings of God; we know that supernatural grace permeates the entire scene, but, as with Joseph, a great deal of the meaning and mechanics of the event are hidden. Still, that divine power and grace is behind the Incarnation is clear to us. The ray is cross-shaped; we are reminded that through the Holy Cross death is destroyed and the world enters into a new path, a path which will finally culminate in a new heaven and a new earth.

Written for Theodoulos

Reflection from St. Hesychios the Priest, who is thought to have lived on Mt. Sinai in the late 8th to early 9th century (c. 750-850 A.D.)

St. Nikodimos identifies the writer of On Watchfulness and Holiness with Hesychios of Jerusalem, author of many Biblical commentaries, who lived in the first half of the fifth century. But it is today accepted that On Watchfulness and Holiness is the work of an entirely different Hesychios, who was abbot of the Monastery of the Mother of God of the Burning Bush (Vatos) at Sinai. Hesychios of Sinai’s date is uncertain. He is probably later than St. John Klimakos (6th or 7th century), with whose book The Ladder of Divine Ascent he seems to be familiar; possibly he lived in the 8th or 9th century.

St. Nikodimos commends the work of St. Hesychios especially for its teaching on watchfulness, inner attentiveness and the guarding of the heart. Hesychios has a warm devotion to the Holy Name of Jesus, and this makes his treatise of particular value to all who use the Jesus Prayer.

Watchfulness produces stillness, which leads us to that inner silence so we can pray as we ought

by St. Hesychios the Priest

1. Watchfulness is a spiritual method, which if sedulously practiced over a period, completely frees us with God’s help from impassioned thoughts, impassioned words and evil actions. It leads, in so far as this is possible, to a sure knowledge of the inapprehensible God, and helps us to penetrate the divine and hidden mysteries. It enables us to fulfill every divine commandment in the Old and New Testaments and bestows upon us every blessing of the age to come. It is, in the true sense, purity of heart, a state blessed by Christ when He says: “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God” (Matt. 5:8); and one which, because of its spiritual nobility and beauty — or, rather, because of our negligence — is to be bought only at a great price. But once established in us, it guides us to a true and holy way of life. It teaches us how to activate the three aspects of our soul correctly, and how to keep a firm guard over the senses. It promotes the daily growth of the four principal virtues, and is the basis of our contemplation.

2. The great lawgiver Moses — or, rather, the Holy Spirit — indicates the pure, comprehensive and ennobling character of this virtue, and teaches us how to acquire and perfect it, when he says: “Be attentive to yourself, lest there arise in your heart a secret thing which is an iniquity” (Deut. 15:9, LXX). Here the phrase “a secret thing” refers to the first appearance of an evil thought. This the Fathers call a provocation introduced into the heart by the devil. As soon as this thought appears in our intellect, our own thoughts chase after it and enter into impassioned intercourse with it.

3. Watchfulness is a way embracing every virtue, every commandment. It is the heart’s stillness and, when free from mental images, it is the guarding of the intellect.

4. Just as a man blind from birth does not see the sun’s light, so one who fails to pursue watchfulness does not see the rich radiance of divine grace. He cannot free himself from evil thoughts, words and actions, and because of these thoughts and actions he will not be able freely to pass the lords of hell when he dies.

5. Attentiveness is the heart’s stillness, unbroken by any thought. In this stillness the heart breathes and invokes endlessly and without ceasing only Jesus Christ. It confesses Him who alone has power to forgive our sins, and with His aid it courageously faces its enemies. Through this invocation enfolded continually in Christ, who secretly divines all hearts, the soul does everything it can to keep its sweetness and its inner struggle hidden from men, so that the devil, coming upon it surreptitiously, does not lead it into evil and destroy its precious work.

6. Watchfulness is a continual fixing and halting of thought at the entrance to the heart. In this way predatory and murderous thoughts are marked down as they approach and what they say and do is noted; and we can see in what specious and delusive form the demons are trying to deceive the intellect. If we are conscientious in this, we can gain much experience and knowledge of spiritual warfare.

7. In one who is attempting to dam up the source of evil thoughts and actions, continuity of watchful attention in the intellect is produced by fear of hell and fear of God, by God’s withdrawals from the soul, and by the advent of trials, which chasten and instruct. These withdrawals and unexpected trials help us to correct our life, especially when, having once experienced the tranquility of watchfulness, we neglect it.

Continuity of attention produces inner stability; inner stability produces a natural intensification of watchfulness; and this intensification gradually and in due measure gives contemplative insight into spiritual warfare. This in its turn is succeeded by persistence in the Jesus Prayer and by the state that Jesus confers in which the intellect, free from all images, enjoys complete quietude.

8. When the mind, taking refuge in Christ and calling upon Him, stands firm and repels its unseen enemies, like a wild beast facing a pack of hounds from a good position of defense, then it will inwardly anticipate their inner ambuscades well in advance. Through continually invoking Jesus the peacemaker against them, it remains invulnerable…

9. If you are an adept, initiated into the mysteries and standing before God at dawn (cf. Ps. 5:3), you will divine the meaning of my words. Otherwise be watchful and you will discover it.

10. Much water makes up the sea. But extreme watchfulness and the Prayer of Jesus Christ, undistracted by thoughts, are the necessary basis for inner vigilance and stillness of soul, for contemplation, for the humility that knows and assesses, for rectitude and love. This watchfulness and this prayer must be intense, concentrated and unremitting.

11. It is written: “Not everyone who says to Me: ‘Lord, Lord’ shall enter into the kingdom of heaven; but he that does the will of My Father” (Matt. 7:21). The will of the Father is indicated in the words: “You who love the Lord, hate evil” (Ps. 97:10). Hence we should both pray the Prayer of Jesus Christ and hate our evil thoughts. In this way we do God’s will…

St. Anthony The Great

Anthony the Great, called “The Father of Monks,” was born in central Egypt about A.D. 251, the son of peasant farmers who were Christian. In c. 269 he heard the Gospel read in church and applied to himself the words: “Go, sell all that you have and give to the poor and come…” He devoted himself to a life of asceticism under the guidance of a recluse near his village. In c. 285 he went alone into the desert to live in complete solitude. His reputation attracted followers, who settled near him, and in c. 305 he came out of his hermitage in order to act as their spiritual father.

Five years later he again retired into solitude. He visited Alexandria at least twice, once during the persecution of Christians and again to support the bishop, Saint Athanasius, against heresy. He died at the age of one hundred and five. His life was written by Saint Athanasius and was very influential in spreading the ideals of monasticism throughout the Christian World.

When Abba Anthony thought about the depth of the judgments of God, he asked, “Lord, how is it that some die when they are young, while others drag on to extreme old age? Why are there those who are poor and those who are rich? Why do wicked men prosper and why are the just in need?” He heard a voice answering him, “Anthony, keep your attention on yourself; these things are according to the judgment of God, and it is not to your advantage to know anything about them.”

—Anthony the Great

“A time is coming when men will go mad, and when they see someone who is not mad, they will attack him saying, ‘You are mad, you are not like us.’”

—Anthony the Great

“Always have the fear of God before your eyes. Remember him who gives death and life. Hate the world and all that is in it. Hate all peace that comes from the flesh. Renounce this life, so that you may be alive to God. Remember what you have promised God, for it will be required of you on the day of judgment. Suffer hunger, thirst, nakedness, be watchful and sorrowful; weep, and groan in your heart; test yourselves, to see if you are worthy of God; despise the flesh, so that you may preserve your souls.”

—Anthony the Great

“Our life and our death is with our neighbor. If we gain our brother, we have gained God, but if we scandalize our brother, we have sinned against Christ.”

—Anthony the Great

Reflection I: “lord, Teach us to Pray” (LK 11:1)

III. Ways of Prayer

Spiritual writers describe many ways of prayer, some of them overlapping and more or less synonymous. There is liturgical prayer, vocal prayer, mental prayer, meditation, contemplation, lectio divina, and hesychia or “the prayer of quiet,” as it was called in the West. Some of these terms are open to misunderstanding. “Mental prayer” or “meditation,” for instance, might be mistaken for just thinking or reflecting, which in itself is not prayer at all. And some spiritual writers devalue “vocal prayer” as if it were second-rate, considered just words recited by rote, with no necessary interiority. Indeed, there have been times in the history of the Church when even liturgical prayer was looked on much in the same way, and considered secondary to contemplation or “interior prayer.”

The truth of the matter, however, is that most methods of prayer include all or at least several of the many ways of prayer: one contemplates an icon, or meditates on a psalm or other scriptural text or spiritual topic; reflection on this holy icon or Divine Word moves one’s heart and inspires one to speak to God about what is on one’s mind and in one’s heart, and then to listen attentively for the response of his grace. The same with vocal prayer or the prayer called lectio divina in the ancient tradition of Western monasticism. It is not just spiritual reading of some pious text, but a slow, prayerful, meditative reading during which one pauses as the heart is moved to ponder and speak to God of what has moved one’s spirit. This is the same as the classic second method of prayer of St. Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises (Sp Ex §§249- 257). St. Jean Baptiste Marie Vianney, better known as the Curé d’Ars, recounts how one of his French peasant parishioners called contemplation a gaze of faith, a communion of love. When asked to describe his prayer before the tabernacle, he said, “I look at Jesus, and He looks at me” (CCC §2715).

All these ways of prayer are found, if under different names, in the classical Eastern and Western spiritual writers. One of my favorites is 19th c. Russian Orthodox Bishop Feofan Zatvornik or Theophan the Recluse, a spiritual master who lived from 1815-1894. Ordained a bishop in 1860, after six years he resigned and retired to a small monastery to live a life of prayer and seclusion. Feofan, who calls prayer “standing before God with the mind in the heart,” distinguishes three degrees of prayer: bodily or vocal prayer, prayer of the mind, and prayer of the heart or “prayer of the mind in the heart.” Oral or vocal prayers, Feofan teaches, in an insight of genius, originated as purely spiritual prayers that only later became oral by being written down. When we pray them now, we must reverse the process, he writes, and enter into the spirit of the prayers which you hear and read, reproducing them in your heart; and in this way offer them up from your heart to God, as if they had been born in your own heart under the action of the grace of the Holy Spirit. Then, and then alone, is the prayer pleasing to God. How can we attain to such prayer? Ponder carefully on the prayers, which you have to read in your prayer book; feel them deeply, even learn them by heart. And so when you pray you will express that which is already deeply felt in your heart.

The same is true of the liturgical chants. Citing the teaching of St. John Chrysostom, Feofan says: “The songs must primarily be spiritual, and sung not only by the tongue but also by the heart.”

By the continual practice of this “prayer with the mind in the heart” one’s prayer becomes spiritualized and takes on a life of its own, becoming “self-moving,” as Feofan calls it, “when prayer exists and acts on its own,” i.e., is moved by the grace of the Spirit, and not by one’s own human will.

Slowly, words disappear from the prayer, which becomes the heart’s wordless unceasing prayer of love. There is nothing whatever in this description of progress in interior prayer that is foreign to Western spirituality, despite the frantic attempts of the cliché–mongers to seek everywhere irreconcilable differences between East and West.

The early hesychasts also evolved a “physical method,”a system of bodily posture and breathing techniques to foster this state of prayer, and there is something akin to it in the “Third Method of Prayer” in St. Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises (Sp Ex §§258). But Feofan and other authoritative 19th c. Russian masters like Bishop Ignatij Brjanchaninov (1807-1867) were somewhat reticent with regard to this “physical method.”

Basically what these authors, East and West, are talking about is what I call the “interiorizing” of vocal and liturgical prayer, taking the written text and making it one’s own by praying it in one’s heart, so that when one returns to it again and again it is no longer someone else’s prayer, but has become the movement of one’s own heart.

Transylvania, presently one of the three major regions of Romania along with Wallachia and Moldavia, became part of Hungary in the early 11th century. Although the principality was also home to large numbers of Hungarians and Germans, who were mostly Latin Catholics, Orthodox Romanians made up the majority of the population. Soon after the province was taken by the Turks in the 16th century, Calvinism became widespread among the Hungarians, and Lutheranism among the Germans.

In 1687, the Hapsburg Austrian Emperor Leopold I drove the Turks from Transylvania and annexed it to his empire. It was his policy to encourage the Orthodox within his realm to become Greek Catholic. For this purpose the Jesuits began to work as missionaries among the Transylvanian Romanians in 1693. Their efforts, combined with the denial of full civil rights to the Orthodox and the spread of Protestantism in the area which caused growing concern among the Orthodox clergy, contributed to the acceptance of a union with Rome by Orthodox Metropolitan Atanasie of Transylvania in 1698. He later convoked a synod which formally concluded the agreement on September 4, 1700.

At first this union included most of the Romanian Orthodox in the province. But in 1744, the Orthodox monk Visarion led a popular uprising that sparked a widespread movement back to Orthodoxy. In spite of government efforts to enforce the union with Rome—even by military means—resistance was so strong that Empress Maria Theresa reluctantly allowed the appointment of a bishop for the Romanian Orthodox in Transylvania in 1759. In the end, about half of the Transylvanian Romanians returned to Orthodoxy.

It proved difficult for the new Greek Catholic community, known popularly as the Greek Catholic Church, to obtain in practice the religious and civil rights that had been guaranteed it when the union was concluded. Bishop Ion Inochentie Micu-Klein, head of the church from 1729 to 1751, struggled with great vigor for the rights of his church and of all Romanians within the empire. He would die in exile in Rome.

The Romanian Greek Catholic dioceses had originally been subordinate to the Latin Hungarian Primate at Esztergom. But in 1853 Pope Pius IX established a separate metropolitan province for the Greek Catholics in Transylvania. The diocese of Fãgãraş–Alba Iulia was made metropolitan see, with three suffragan dioceses. Since 1737 the bishops of Fãgãraş had resided at Blaj, which had become the church’s administrative and cultural center.

At the end of World War I, Transylvania was united to Romania, and for the first time Greek Catholics found themselves in a predominantly Orthodox state. By 1940 there were five dioceses, over 1,500 priests (90% of whom were married), and about 1.5 million faithful. Major seminaries existed at Blaj, Oradea Mare, and Gherla. A Pontifical Romanian College in Rome received its first students in 1936.

The establishment of a communist government in Romania after World War II proved disastrous for the Romanian Greek Catholic Church. On October 1, 1948, 36 Greek Catholic priests met under government pressure at Cluj-Napoca. They voted to terminate the union with Rome and asked for reunion with the Romanian Orthodox Church. On October 21 the union was formally abolished at a ceremony at Alba Iulia. On December 1, 1948, the government passed legislation which dissolved the Greek Catholic Church and gave over most of its property to the Orthodox Church. The six Greek Catholic bishops were arrested on the night of December 29-30. Five of the six later died in prison. In 1964 the bishop of Cluj-Gherla, Juliu Hossu, was released from prison but placed under house arrest in a monastery, where he died in 1970. Pope Paul VI announced in 1973 that he had made Hossu a Cardinal in pectore in 1969.

After 41 years underground, the fortunes of the Greek Catholic Church in Romania changed dramatically after the Ceauşescu regime was overthrown in December 1989. On January 2, 1990, the 1948 decree which dissolved the church was abrogated. Greek Catholics began to worship openly again, and three secretly ordained bishops emerged from hiding. On March 14, 1990, Pope John Paul II reestablished the hierarchy of the church by appointing bishops for all five dioceses.

Unfortunately the reemergence of the Greek Catholic Church was accompanied by a confrontation with the Romanian Orthodox Church over the restitution of church buildings. The Catholics insisted that all property be returned as a matter of justice, while the Orthodox held that any transfer of property must take into account the present pastoral needs of both communities. As of mid-1998 this impasse had not been overcome. The Greek Catholics claim that they have received back only 97 of their 2,588 former churches, mostly in the Banat region where Orthodox Metropolitan Nicolae has been more willing to allow the return of Greek Catholic property.

Seminaries are functioning at Cluj, Baia Mare, and Oradea, and theological institutes have been set up in Blaj, Cluj and Oradea. The remains of Bishop Ion Inochentie Micu-Klein were returned to Romania and buried in Blaj in August 1997. In 1998 proceedings were initiated in Rome for the possible canonization of the Greek Catholic bishops who died during the communist persecutions. In Romania this church calls itself “The Romanian Church United with Rome.”

Provincial councils of the Romanian Greek Catholic Church were held at Blaj from May 5 to 14, 1872, from May 30 to June 6, 1882, and from September 13 to 26, 1900. These councils passed legislation concerning various aspects of church life, and all were approved by the Holy See. The first session of the fourth provincial council took place at Blaj from March 17 to 21, 1997. It was to be celebrated in five sessions over a four-year period, to be concluded in 2000.

The size of the Romanian Greek Catholic Church is hotly disputed. The Greek Catholics themselves officially claim just over one million members (reflected in the figure given below) and in some publications state that they have as many as three million. A Romanian census carried out in January 1992 reported only 228,377 members, a figure the Greek Catholics firmly rejected.

The only diocese outside Romania is St. George’s in Canton of the Romanians, which includes all the faithful in the United States, headed by Bishop John Michael Botean (1121 44th Street NE, Canton, Ohio 44714). The diocese has 15 parishes for 5,300 faithful. A community was recently formed in Sydney, Australia, under the pastoral care of Fr. Michael Anghel, 74 Underwood Road, Homebush 2140.

LOCATION: Romania, USA, Canada HEAD: Metropolitan Lucian Mureşan (born 1931, appointed 1994) TITLE: Archbishop of Fãgãraş and Alba Iulia RESIDENCE: Blaj, Romania MEMBERSHIP: 1,119,000

Silence is indispensable for prayer

by Pope Emeritus Benedict

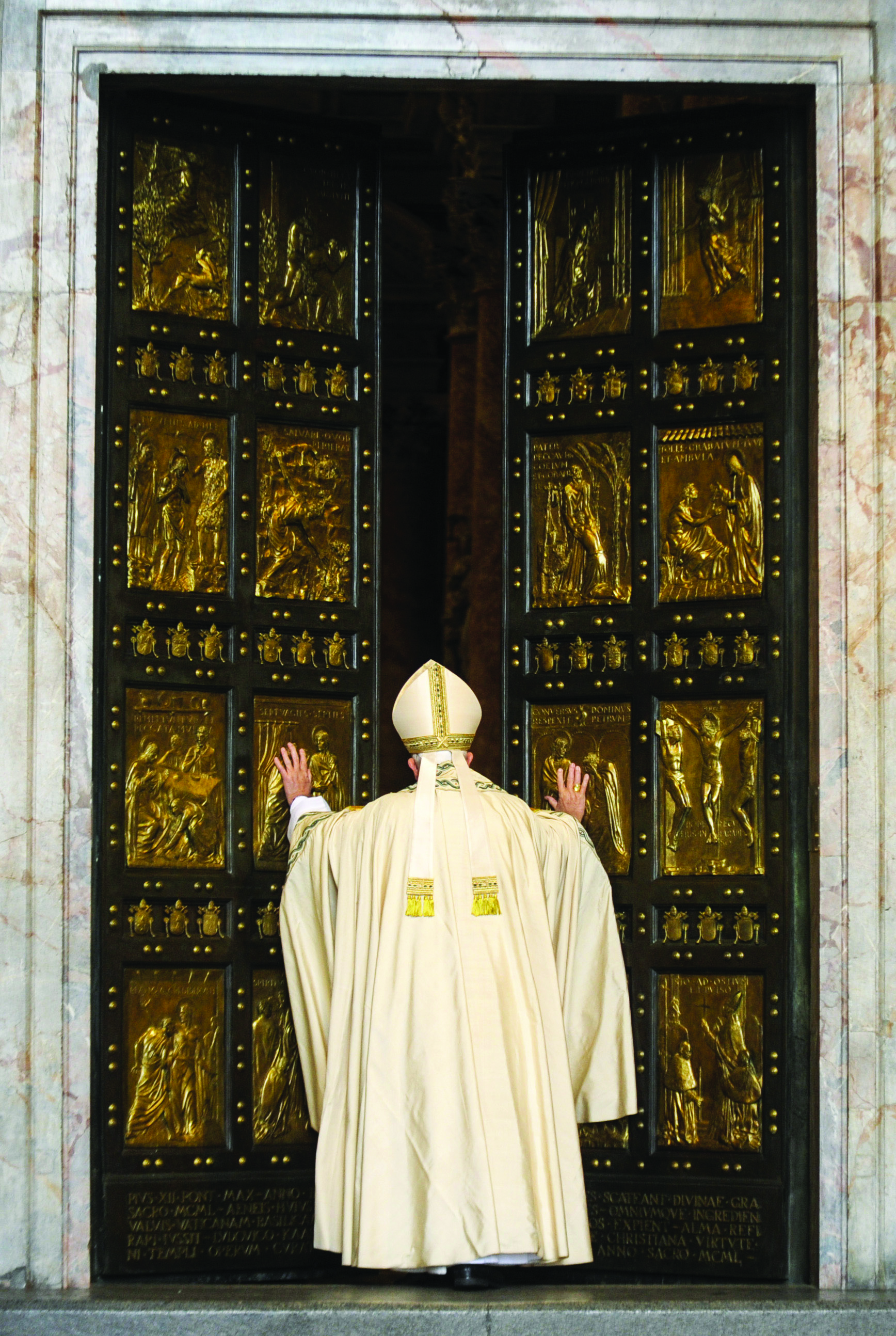

….The Cross of Christ does not only demonstrate Jesus’ silence as his last word to the Father but reveals that God also speaks through silence: “The silence of God, the experience of the distance of the almighty Father, is a decisive stage in the earthly journey of the Son of God, the Incarnate Word. Hanging from the wood of the cross, he lamented the suffering caused by that silence…. ”

Jesus’ experience on the cross profoundly reveals the situation of the person praying and the culmination of his prayer: having heard and recognized the word of God, we must also come to terms with the silence of God, an important expression of the same divine Word.

The dynamic of words and silence, which marks Jesus’ prayer throughout his earthly existence, especially on the cross, also touches our own prayer life in two directions.

The first is the one that concerns the acceptance of the word of God. Inward and outward silence is necessary if we are to be able to hear this word.

In our time this point is particularly difficult for us. In fact, ours is an era that does not encourage recollection; indeed, one sometimes gets the impression that people are frightened of being cut off, even for an instant, from the torrent of words and images that mark and fill the day. ….

“Rediscovering the centrality of God’s word in the life of the Church also means rediscovering a sense of recollection and inner repose. The great patristic tradition teaches us that the mysteries of Christ all involve silence. Only in silence can the word of God find a home in us” …. This principle—that without silence one does not hear, does not listen, does not receive a word—applies especially to personal prayer as well as to our liturgies: to facilitate authentic listening, they must also be rich in moments of silence and of non-verbal reception.…

The Gospels often present Jesus, especially at times of crucial decisions, withdrawing to lonely places, away from the crowds and even from the disciples in order to pray in silence and to live his filial relationship with God. Silence can carve out an inner space in our very depths to enable God to dwell there, so that his word will remain within us and love for him take root in our minds and hearts and inspire our life. Hence the first direction: relearning silence (watchfulness), openness to listening (attentiveness), which opens us to the word of God.

However, there is also a second important connection between silence and prayer. Indeed it is not only our silence (attentiveness) that disposes us to listen to the word of God; in our prayers we often find we are confronted by God’s silence. We feel, as it were, let down; it seems to us that God neither listens nor responds. Yet God’s silence, as happened to Jesus, does not indicate his absence. Christians know well that the Lord is present and listens, even in the darkness of pain, rejection and loneliness.

Jesus reassures his disciples and each one of us that God is well acquainted with our needs at every moment of our life. He teaches the disciples: “In praying do not heap up empty phrases as the Gentiles do; for they think that they will be heard for their many words. Do not be like them, for your Father knows what you need before you ask him” (Mt 6:7-8)….

In the Bible Job’s experience is particularly significant in this regard. It truly seems that God’s attitude to him was one of abandonment, of total silence. …. In spite of all, he keeps his faith intact, and in the end, discovers the value of his experience and of God’s silence…. “I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees you” (Job 42:5). Almost all of us know God only through hearsay and the more open we are to his silence and to our own silence, the more we truly begin to know him…. St. Francis Xavier prayed to the Lord saying: “I do not love You because You can give me paradise or condemn me to hell, but because You are my God. I love You because You are You”….

“The drama of prayer is fully revealed to us in the Word who became flesh and dwells among us. To seek to understand his prayer through what his witnesses proclaim to us in the Gospel is to approach the holy Lord Jesus as Moses approached the burning bush: first to contemplate him in prayer, then to hear how he teaches us to pray, in order to know how he hears our prayer” Catechism of the Catholic Church (n. 2598)….

How does Jesus teach us to pray?

We find a clear answer in the Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: “Jesus teaches us to pray not only with the Our Father” — certainly the high point of his instruction on how to pray — “but also when he prays. In this way he teaches us, in addition to the content, the dispositions necessary for every true prayer: purity of heart that seeks the Kingdom and forgives enemies, bold and filial faith that goes beyond what we feel and understand, and watchfulness that protects the disciple from temptation” Catechism of the Catholic Church (n. 544)….

In going through the Gospels we have seen that concerning our prayers the Lord is conversation partner, friend, witness and teacher. The newness of our dialogue with God is revealed in Jesus: the filial prayer that the Father expects of his children. And we learn from Jesus that constant prayer helps us to interpret our life, make our decisions, recognize and accept our vocation, discover the talents that God has given us and do his will daily, the only way to fulfill our life.

Jesus’ prayer points out to us, we are all too often concerned with operational efficacy and the practical results we achieve, that we need to pause, to experience moments of intimacy with God, “detaching ourselves” from the everyday commotion in order to listen, to go to the “root” that sustains and nourishes life.

Christmas Prayer

Kontakion – Tone 3

Today the Virgin gives birth to the Transcendent One, and the earth offers a cave to the Unapproachable One! Angels and shepherds glorify Him! The wise men journey with a star! Since for our sake the Eternal God was born as a little child!

Facebook Comments