We continue our series on the spirituality and practices of Eastern Christianity by looking at liturgical themes of the penitential season of “Great Lent”

The Crucifixion Icon

– By Robert Wiesner

Any time is a good time to contemplate the saving cross of Jesus Christ, but Lent is an especially appropriate season to take a close look at the image of our crucified Lord, God and Savior. As with all icons, entering into the spirit and meaning of the image is simplified with a bit of explanation.

The icon shares several characteristics with depictions of the same scene in Western art. The major figures of Mary and John appear, for instance. But a closer look reveals some crucial differences in theology, some so important that many Eastern Christian commentaries warn against any close contemplation of Western examples!

The most striking difference lies in the depiction of Christ Himself. The West concentrates attention upon the human suffering of the cross. The icon, while including the wounds of a cruel death, yet does not show Jesus in an attitude of torment. Rather, He radiates a rather calm serenity and repose. The inscription of “The King of Glory” explains the dignity of the Crucified One. Upon the cross, Christ is actually occupying His throne and the cross is the scepter with which the world is ruled and judged. The idea is reinforced with the words “IC XC NIKA” or “Jesus Christ conquers.” Christ’s halo always includes the Greek abbreviation for the words “I Am Who Am.” To artistically reduce such a kingly figure to a mere human in torment would be held as heretical in many quarters! The icon includes a great deal more vital information concerning the divinity of Christ that is largely lost in Western art.

The cross itself is a three-beamed object, containing a foot-rest which is usually shown at a slant.

Traditionally, Dismas, the good thief, was held to be crucified on Christ’s right; the foot rest slants upward to the right to indicate the ultimate destination of Dismas.

The downward slant would then indicate a less happy outcome for the unrepentant one on the left. The bar also indicates that the cross is become the seat of judgment for humanity; how we bear the cross in earthly life determines our being numbered among the sheep or with the goats.

Underneath the cross is seen a skull and sometimes crossed arm bones. Golgotha, the Place of the Skull, was not so named due to the executions taking place, but rather because it was held to be the very burial place of Adam. The earthquakes which accompanied the crucifixion opened Adam’s tomb, among others. The place of Adam’s burial becomes the very site where redemption for his race is accomplished by the new Adam! Adam’s death is vanquished by the saving death of Jesus as the cross becomes the new and true Tree of Life.

The Eucharistic significance of the Sacrifice is indicated by the crossed arm bones, the very gesture with which Eastern Christians receive the Lord in Communion. Often two angels are shown, each bearing an instrument used in the crucifixion, one a lance and the other a reed with a sponge upon it. This echoes another icon, “The Mother of God of the Passion,” usually known as “Perpetual Help” in the West. There, the young Christ, nestled in His Mother’s arms, looks upon the implements of torture He is to face. The angels could have come to His aid on Golgotha, but their bearing these tools bears witness to an acceptance of God’s human nature. Some believe that the demons rejected the notion that God should join divinity to humanity so intimately, that it was somehow a slight upon angelic nature. The loyal angels fully accepted the elevation of human nature, accomplished by the humiliation of the Son Of God on a cross. Space permits no more, but as usual with icons, the theology of the Crucifixion could fill an encyclopedia!

The Great Canon of Repentance of St. Andrew of Crete

“Come, wretched soul, with your flesh, confess to the Creator of all. In the future refrain from your former brutishness, and offer to God tears of repentance.”

—The Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete (Monday: Ode 1, v. 2)

The Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete, the longest canon in the all Orthodox services for the year, is read in church in serialized form the first four nights of Great Lent, at Great Compline, and in its entirety at Matins for Thursday of the fifth week of Great Lent.

Written for his personal meditation, the ancient and monumental liturgical hymn is a moving dialog of both humility and hope between St. Andrew and his soul. In it, he contemplates his own sinfulness and God’s mercy, and exhorts himself to repent and change his life. It contains hundreds of biblical references and mystical explanations, from both Old and New Testaments, Trinitarian doxologies and hymns to the Theotokos (Mother of God) in its nine “odes.”

The Canon of St. Andrew of Crete is considered an incomparable example of Orthodox liturgical hymnody, both in its scope and complexity, and in its poetic beauty.

“The end is drawing near, my soul, is drawing near! But you neither care nor prepare. The time is growing short. Rise! The Judge is at the very doors. Like a dream, like a flower, the time of this life passes. Why do we bustle about in vain?”

(Monday: Ode 4, v. 2)

Born in Damascus of Christian parents, St. Andrew of Crete was unable to speak until the age of seven. The power of speech was given to him one day when his parents took him to church to receive Communion.

At the age of 14 he went to Jerusalem and was tonsured in the monastery of St. Sava the Sanctified. In his understanding and ascesis, he surpassed many of the older monks, and the Patriarch took him as his secretary.

When the Monothelite heresy, which taught that the Lord had no human will but only a divine one, began to rage, the Sixth Ecumenical Council met in Constantinople in 681, in the reign of Constantine IV.

Theodore, Patriarch of Jerusalem, unable to attend, sent Andrew, then a deacon, as his representative. There Andrew’s gifts became apparent: his eloquence, his zeal for the Faith, and his rare prudence.

After being instrumental in confirming the Orthodox faith, Andrew returned to his work in Jerusalem. Eventually, Andrew was enthroned as archbishop of the island of Crete, where he was greatly beloved by his flock.

In his zeal for Orthodoxy, he strongly withstood heresy. He was known to work miracles through his prayers, driving the Saracens from the island of Crete by means of them.

Among the many learned books, poems and canons he authored is the Great Canon of Repentance, which is read in full on the Thursday of the Fifth Week of the Great Fast (Lent). It was said of him, “Looking at his face and listening to the words that flowed like honey from his lips, each man was touched and renewed.

”Returning from Constantinople in about the year 740, Andrew foretold his death before reaching Crete. And so it happened: as the ship approached the island of Mitylene, this light of the Church finished his earthly course and his soul went to the Kingdom of Christ.

ROBERT TAFT, SJ, is an American Jesuit priest and archimandrite of the Eastern Catholic Church. He is an expert in Oriental liturgy and a former professor emeritus of the Pontifical Oriental Institute in Rome. He now resides in Weston, Massachusetts, USA.

For more information about the monthly journal THEOSIS: Spiritual Reflections from the Christian East, edited by Jack Figel, visit www.ecpubs.com, or write: Eastern Christian Publications, PO Box 146, Fairfax, VA, USA, 22038-0146

REFLECTION 1: “LORD, TEACH US TO PRAY” (LUKE 11:1) (CONTINUED)

IV. The Prayer of the Busy Person

So this is the type of prayer I would like you to learn from these reflections. I call it “the prayer of the busy person,” a way of prayer suitable for non-monastic priests and others busily engaged in the pastoral ministry and distracted by the cares of administering a parish while at the same time, perhaps, bringing up and supporting a family. This sort of life is very much like the one I live as a Jesuit, and this is the sort of prayer I have learned to do amidst the hectic cares of my work. Though vowed to the monastic ideal in the Eastern sense of the educated monks of Orthodoxy engaged in the work of the Church, Jesuits lead a busy active life in the world. The underlying Ignatian or Jesuit vision of this world, inherited from our Founder St. Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556), is that only God can save it, but that he has chosen to use us as instruments in so doing. One of my favorite prayers, that of St. Teresa of Avila (1518-1582), a contemporary of St. Ignatius, expresses this vision perfectly:

Christ has no body now but yours, no hands but yours, no feet but yours.

Yours are the eyes through which Christ’s compassion must look out on the world, yours are the feet with which He is to go about doing good.

Yours are the hands with which He is to bless us now.

This same vision is expressed in the Byzantine liturgical tradition by the feasts, known as the synaxis in Greek, or sobor in Slavonic, which fall in the liturgical calendar on the day following a major feast of Salvation History. They celebrate the role of those human figures intimately associated with the Saving Mystery of the preceding day.

The Synaxis of the Mother of God

Mary’s parents Saints Joachim and Anna on September 9, the day after the Nativity of the Theotokos;

Mary the Mother of God on December 26, the day after the Nativity of her Divine Son;

St. John the Baptist on January 7, the day after the Theophany and Baptism of Jesus.

All indicate the same doctrine of our faith: that by entering our human history through the Incarnation of his Divine Son, God willed to associate us in his work of salvation.

This vision, equally Ignatian and Byzantine, is fundamentally different from the modern humanistic and secular social ideal, which pretends that humans can of themselves create the society they choose, free of human despotism, historical determinism, and supernatural authority. But is it equally different from the ideal of early and Eastern monasticism, with its radical eschatological orientation and rejection of this world.

On the contrary, Ignatian service and prayer, in the words of Jesuit Karl Rahner (1904-1984), whom many consider the greatest Catholic theologian of the 20th century, is rooted in a positive, amicable, and joyous relationship with the world. As the former Jesuit Father General Peter-Hans Kolvenbach (1928–) noted, Ignatian spirituality “does not insist on seeking God outside of created things, but rather on finding Him in them and recognizing fully their autonomous existence in a state of dependence as created objects.”

The condition of this cooperation in God’s design for the human race, however, is that we, the human instruments, be united with God. And that is where prayer comes in. Without prayer there is no such thing as a spiritual life, no possibility of being united with God, no chance of being his instrument in the salvation of the world — and, I might add, no chance of living a happy and fulfilled priestly or religious life; without prayer we are not living in and with God. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church states peremptorily: “Prayer is a vital necessity. Prayer and Christian life are inseparable” (CCC §§2744-2745).

Immersed in this world, we need the “Bless this Mess” spirituality so aptly expressed by Michael Hollings, the harried, overworked urban parish priest of St. Mary of the Angels, Bayswater, London, in an article in the April 29, 1988 London Tablet.

Describing his years of study in Rome, Fr. Hollings recalls “Bobby” Dyson, S.J., who was a Byzantine Rite Jesuit I had the privilege of meeting and serving as cantor at his Divine Liturgy during my first visit to Rome in May 1959. This was on my way back to the US from my years of teaching in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1956-1959, when I stayed at the Biblical Institute where Dyson was professor. Hollings describes how in Rome the most memorable lecturer was a Jesuit, Fr. Dyson of the Biblical Institute. “In four years of scripture lectures, we covered almost everything under heaven, without ever moving beyond the first three chapters of Genesis… One phrase has always remained in my mind from Fr. Dyson’s teaching about creation. The Hebrew for the early state of the earth was “tohu” and “bohu” — “trackless waste and emptiness.” Since I began to think and pray seriously, I have come to realize that tohu and bohu was not only the situation at the dawn of the world but continues where I stand today. It is upon this formless mass, this mess, that God works.”

This so resonated with the way my life sometimes seems that I have saved that clipping these 24 years, and still derive wry consolation from it every time I read it. The active life of a minister in today’s Church is tohu and bohu indeed, but we can let God give it form and shape through our prayer.

(To be continued...)

from Theosis: Spiritual Reflections from the Christian East

By Archimandrite Robert Taft, SJ

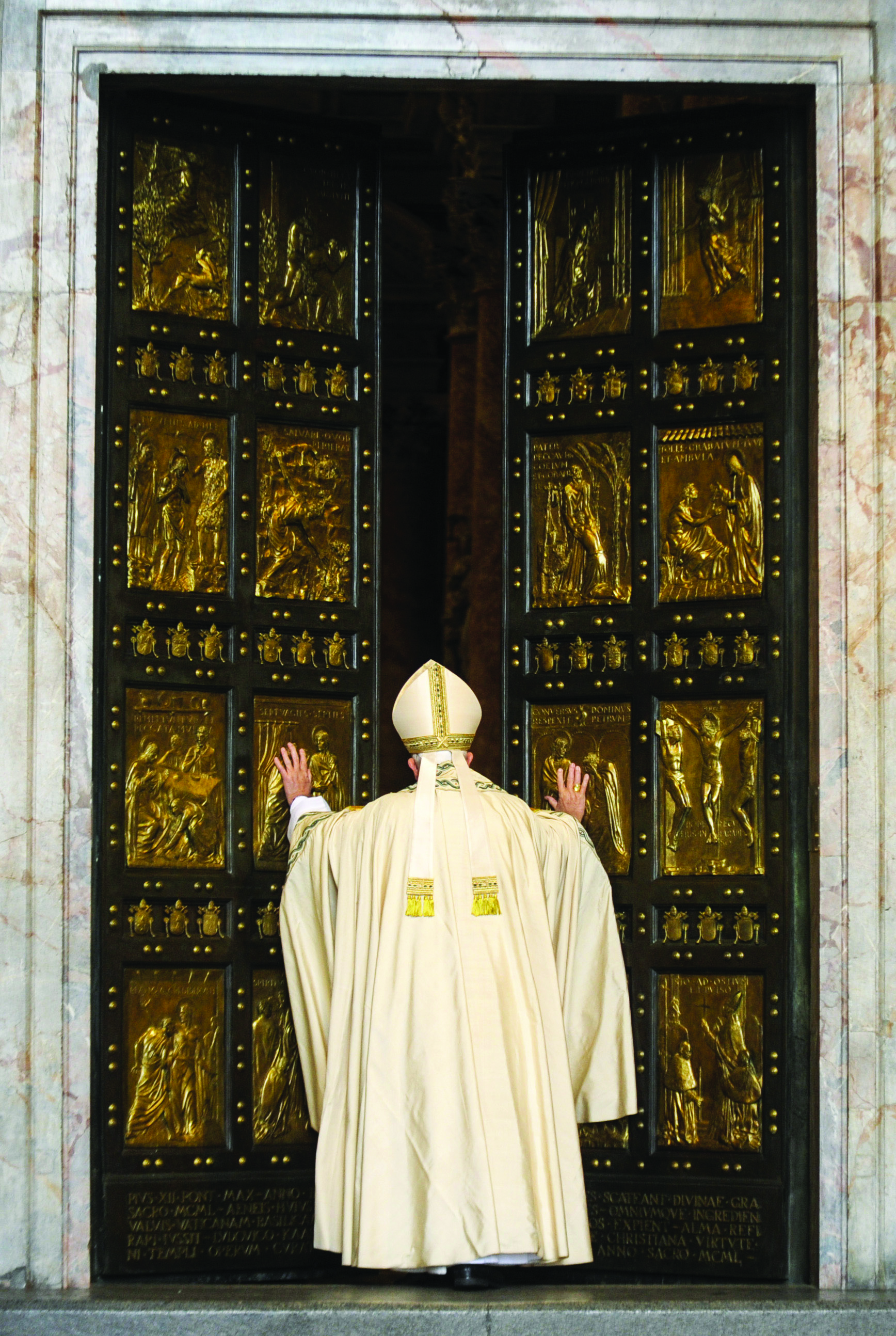

Oriental Orthodox-Catholic Meeting Concludes in Rome

Vatican Radio, January 31 – The International Joint Commission for the Theological Dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Oriental Orthodox Churches met in Rome during the last week in January. Their discussions dealt with expressions of communion in the Early Church and ended with an audience with Pope Francis.

Fr. Mark Sheridan, a Benedictine monk now based in Jerusalem, has been a member of the dialogue since the first meeting in 2004. He explained that the dialogue deals with the Orthodox Churches of the Coptic, Armenian, Syriac, Indian, Ethiopian, and Eritrean traditions and the Catholic Church.

“These are the Churches that did not accept the statements of the Council of Chalcedon in the fifth century that professed that Christ was one person with two natures, a human and a divine,” he said.

A separate dialogue deals with relations between the Orthodox Churches of the Byzantine tradition.

Fr. Sheridan commented on the Pope’s most recent statements regarding ecumenical dialogue.

“One could get lost in the things that are not of the greatest importance,” he said. “This is a very wise observation [on the Pope’s part]. We in the Catholic Church distinguish between a hierarchy of doctrines and teachings. There can be great variety in expression of teaching while agreeing on the basics.”

Fr. Sheridan noted that the Pope, during his discourse in the Church of St. George in Istanbul on November 30, said that the Catholic Church did not seek subordination of the other churches.

He also said the only terms of reunion would be the acceptance of the Creed.

The commission completed a document this week entitled, “The Exercise of Communion in the Life of the Early Church and Its Implications for Our Search for Communion Today,” and presented the document to Pope Francis.

Summarizing the document, Fr. Sheridan noted six ways that the Early Church communicated and expressed communion in the first five centuries, including letters and visits both formal and informal: synods and councils; prayer; a shared veneration of common martyrs and saints; the spread of monasticism; and pilgrimages.

“In all these Churches, there was a great deal of communication and sharing,” he said.

Fr. Sheridan said the members of the joint commission want the public to know about their work. “All these Churches are very important in the history and diffusion of Christianity. In the Catholic Church there is not just the Latin Church, we also have [Eastern] Catholic Churches… the Church is a many-splendored reality and her splendor is reflected in all of these Churches. We are working for Christian unity and would like the rest of the Church to know about it.”

Global Call For Release of Eritrean Orthodox-Church Head, Under House Arrest For Eight Years

By Lucinda Borkett-Jones, January 26, 2015 – As the eighth anniversary of the removal of the Eritrean Orthodox Patriarch passes, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) has issued a global call for his release.

Patriarch Abune Antonios, head of the Eritrean Orthodox Church, is the rightful leader of the East African country’s largest religious community.

The Eritrean authorities removed him from his position in January 2006 for failing to comply with a government order to excommunicate 3,000 parishioners who had opposed the government.

Antonios had also called for the release of political prisoners.

In May 2007, he was taken from his home and put under house arrest. The government replaced Antonios with Bishop Dioscoros of Mendefera.

“We call on the Eritrean government immediately to release Patriarch Antonios and the more than 2,000 people imprisoned for their religious beliefs. Religious freedom is a fundamental, universal human right,” said Lantos Swett, chair of USCIRF in a statement.

“Unfortunately, this anniversary reminds us that these rights, as well as other human rights, have been denied to the people of Eritrea for more than two decades,” he added.

The Commission said the Patriarch suffers from severe diabetes and has been denied access to medical assistance.

Eritrea is listed ninth on Open Doors’ World Watch List of the 50 countries where it is most difficult to live as a Christian.

Since 2002 only four religious communities have been recognized by the regime, which has been governed by President Isaias Afweki since 1993.

The four recognized religions are the Coptic Orthodox Church of Eritrea, Sunni Islam, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Evangelical Church of Eritrea. But the government has a tight control on all religious activities —even those that are registered.

But without this recognition, religious groups cannot gather in public. The situation is particularly difficult for Evangelical and Pentecostal Christians and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Those who are imprisoned on religious grounds, often not on any formal charges, can be subject to mistreatment and torture. Some Protestants and Evangelicals who have been released report being pressured to give up their faith.

The Orthodox Metropolitan Sees Path to Full Communion Between Catholic and Orthodox Faithful

The Orthodox Metropolitan of Pergamon, Ioannis (John) Zizoulas, co-chair of the Joint International Commission for Theological Dialogue Between the Catholic Church and Orthodox Church, said in December that “‘collaboration’ is not enough. Our greatest wish is to achieve full communion in the Eucharist and across the Church’s structures.”

Metropolitan Zizoulas said the Pope’s declaration in Istanbul in November that the Catholic Church “does not intend to impose any conditions except that of the shared profession of faith” was “powerful” and “a big step forward.”

“Because for many centuries, the Orthodox believed that the Pope wanted to subjugate them. And now we see this is not in any way true,” he said.

“Furthermore, in some parts of the world like the Middle East, Christians are suffering and their persecutors do not stop to ask them whether they are Catholic or Orthodox… we are seen as one family.”

A New Diocese For Ethiopia and a New Metropolitan for Erithrea

Pope Francis has established a new Eastern Catholic Church for Eritrea’s 155,000 faithful — the first new Church formally erected since the early 20th century.

According to a January 19 announcement, Pope Francis has separated the four Eritrean eparchies (dioceses) from the Ethiopian Catholic Church and created a new metropolitan sui iuris (“of its own law”) Church for Eritrea. The pontiff has named Bishop Menghesteab Tesfamariam of Asmara, Eritrea’s capital, as the Church’s first metropolitan archbishop, and henceforth head of the Church.

Located in the Horn of Africa, Eritrea has been criticized by human rights organizations for severe government repression.

Facebook Comments