The Bible is a treasure that God, in His goodness, has given us through the men to whom He confided the mission of communicating His divine message.

It is a book that should be approached with reverence, in fear and trembling. Kierkegaard put it well: the Bible should be read on one’s knees. This is a pre-condition for properly understanding its message. An upsetting fact is that Holy Writ is possibly one of the most misunderstood of all writings. We need only think of the innumerable Protestant sects that have developed since Luther broke away from the Church in the 16th century. There are thousands of them; many die, and new ones are constantly born.

It was an act of Holy Daring on the part of God to share His divine wisdom with human beings whom He knew to be of limited intelligence, and moreover whose minds had been affected by original sin. The effect of this sin was to make us blind to certain truths, the luminosity of which prevented us from perceiving them.

Who — if anyone — has the true interpretation of this sacred text? That many respectable and religiously-minded people have read it and offered such a multiplicity of interpretations, inevitably leads us to the question: is anyone right? Or should we accept the fact that each sect sees some truths and overlooks or misunderstands others?

The obvious answer is: we need a Magisterium — that is, a supreme authority which has received God’s guarantee that the Bible will be correctly read and interpreted.

To be on one’s knees is crucial; it is not enough. We need an authority the validity of which is guaranteed by God Himself.

Let us limit ourselves to briefly examining the different interpretations that can be given to the word “naked.” It is mentioned very many times in the Holy Book, and this fact should elicit our reverent attention. Why is it so often mentioned?

That Adam and Eve, after their sin, discovered to their shame that they were “naked” is open to various interpretations. Some are plainly contradictory. Others are complementary, that is, they shed light on the question from different angles.

Let us offer one: it can be argued that when our first parents discovered their “nakedness” they became aware that their sin had stripped them of the white veil of innocence that had been theirs. They discovered their “nakedness,” that is, the dreadful poverty of a creature that has chosen to cut off his bond with his Creator.

Nakedness, in this sense, means misery.

Later, when Ham, Noah’s son, discovered his father’s nakedness, instead of covering him, he informed his two brothers that he had seen him stripped of his clothes. His duty, clearly, had been to cover him. He failed to do what he was in duty called to do. Upon hearing this, Shem and Japheth entered their father‘s tent and, reverently, walking backward, put a vestment upon him. When informed of what had happened, Noah cursed his youngest son. A father’s curse is something terrible indeed. Should we draw the conclusion that nakedness in this case means “ugly” or “evil”?

Not at all; it means intimacy, secrecy, mystery; it has a note of sacredness that calls for reverence. What is sacred must be approached with trembling reverence. Ham’s attitude was irreverent, and this is why he incurred such a terrible punishment.

In Exodus, Moses informs the Chosen People that they should not “go up the steps of my altar, that your nakedness be not imposed on it” (Exodus 20:26). The altar is a sacred place, and he alone who is reverently attired may ascend the steps leading to it. It is luminously clear that the state of nakedness is not the proper way to perform such religious duties. What is sacred calls for the proper clothing, the proper vestment.

The same theme is developed later in the same sacred book. Aaron and his sons are chosen to exercise cultic functions. They are ordered to wear linen breeches “to cover their naked flesh” (28:42).The whole chapter is dedicated to the importance of “holy vestments” (28:1). It is not a “footnote”; it is solemnly declared and commanded. In Deuteronomy, there is a very severe passage in which God tells his people: “Because you did not serve the Lord your God with joyfulness and gladness of heart, by reason of the abundance of all things” (28:48), a terrible punishment follows. They will have “to serve their enemies… in nakedness.” By refusing to give proper honor to God, rejoicing in serving him, the Chosen People incur this terrible punishment. Once again, nakedness means poverty and misery. To choose to be cut off from one’s creator means metaphysical nakedness. Without Him, we are indeed dust, and unto dust we shall return.

A verse of Isaiah (47:3) echoes the same theme: “Your nakedness shall be uncovered and your shame shall be seen.” Indeed, to be severed from our Creator and Father, is to choose shame. It is an ever-recurring theme in the Old Testament.

In Jeremiah, we read the following: “It is for the greatness of your iniquity that your skirts are lifted up” (13:22).

Our misery, our poverty, our squalor all refer to the same thing: man tries to live without Him to whom he owes his existence, Him who is Life itself. The whole Chapter 16 is on the same theme: to cover our nakedness, and wrap us in silk, i.e. God’s love and help. This great prophet develops this theme further in Chapter 22 and Chapter 23.

In Nahum (3:5), the same thought is highlighted. “I will lift your skirts over your face, and will let nations look on your nakedness and kingdoms on your shame.” It seems quite clear that “nakedness” is linked to sin, and sin is always a turning against God.

Habakuk, another prophet, condemns in the most severe words the person who inebriates others “to gaze on their shame” (2:15).

The Old Testament is not ambiguous: nakedness refers to poverty, ugliness, sin. We need to be clothed with God’s love and mercy, for by ourselves, we are stripped of any goodness. We are rightly ashamed of this wretchedness.

Even though the above quotes all refer to “shame” in a negative sense, it should also be mentioned that there is a totally different type of “shame” (Dietrich von Hildebrand suggested holy bashfulness), the response due to what is intimate, personal, secret, sacred. We are told in the New Testament that when we fast or give alms, this should not be advertised, as the Pharisees did. When a saint receives exceptional graces, he or she “hides” the secrets of the King. Therefore, there is also a “glorious” shame (Proverbs 70: there is a shame which is a source of sin; there also is a shame which is glory and grace). It is unfortunate that the poverty of the human vocabulary uses the same word for things which are radically different.

In the New Testament, we find fewer references to this theme. Still, St. John writes in Revelation (3:18) lines echoing the same theme: “Therefore I counsel you to buy from me gold refined by fire, that you may be rich, and white garments to clothe you and to keep the shame of your nakedness from being seen.”

It is an ever-recurring theme in the symphony of redemption; without God, we are indeed naked.

In both the Old and the New Testament, we are commanded to “clothe the naked.” The secularist interpretation is likely to be that without clothes, we are likely to freeze. The shallowness of this view should be obvious to anyone who lives in warm climates.

Throughout the Bible, vestments and clothing are always a sign of dignity. Jacob manifested his special love for Joseph, the son of his beloved Rachel, by making him a long robe with sleeves (Genesis 37:3). Why does the holy writer mention “sleeves”? They clearly indicate that the whole body was covered by this loving gift. This kindled the jealousy of his brothers. When his siblings put him in a cistern, they stripped him of “his long robe with sleeves” (37:23). But when the same Joseph saved Egypt from starvation, he was rewarded by Pharaoh and “arrayed with garments of fine linen” (Genesis 40-42).

Judith, one of the female heroines of the Old Testament, feeling that she was called to save her people from the brutality of Holofernes, first turned to God for help, and did penance, spreading ashes over her head and wearing a sackcloth for vestment. When the moment was come to achieve her mission, she “put off her widow’s garments and arrayed herself with the gayest apparel” (Judith 10:3). Thanks to her magnificent clothing (which she had worn when her husband was alive), she knew she would attract the brutal tyrant. We all know the end of the story.

Queen Esther, when informed by her uncle of Haman’s plan to exterminate the Jews, knew she was called to save her people. Infringing upon the severe prohibition to enter the King’s chambers without being invited, she heroically risked her life. Thank God, He protected her, and she calmed the King’s wrath. As we know, she invited him to a banquet. Putting all her hope in God, she first took off her splendid apparel, and put on “the garments of distress and mourning and covered her head with ashes and dung” (clearly recognizing our poverty without God’s help) but when going to the banquet, she put on her royal robes, and her beauty appeared in all its charm and grace (Esther, 4 and 5). Once again, we know the end of the story: she puts all her trust in God; she does penance and prays; and then, the “theme” is to put all the natural beauty that God has given her at His service. She triumphed because she put all her trust in God, while acknowledging man’s poverty.

Leviticus gives the Jewish people detailed and strict instructions as to how divine worship should be celebrated. The High Priest had to don special garments, each of which had a symbolic meaning and was meant to be a form of prayer. The sacred calls for sacred vestments. How many Catholics today, infected by the Zeitgeist (the “spirit of the age”) have become blind and deaf to a message that is so crucial to teach us reverence? All five senses should be given the seal of the supernatural.

In celebrating the Most Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, the priest — before Vatican II — had to wear seven different pieces of clothing. Now they have been reduced to three (or is it four?). This change is regrettable because it indicates that we have lost a sense for mystery and symbolism. This language can only be understood by those approaching the sacred mysteries with trembling reverence.

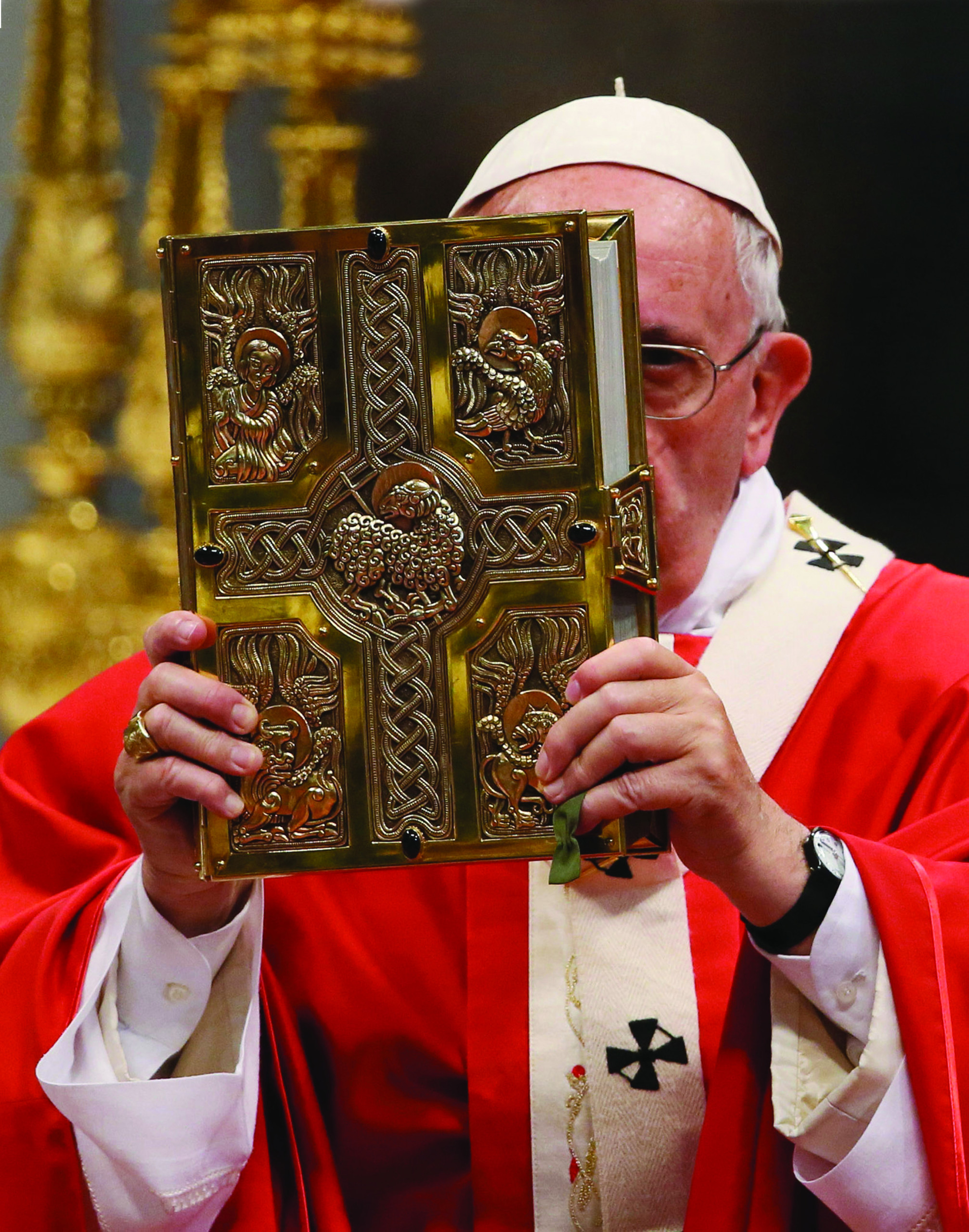

The Pope dons a white robe. The cardinal receive a red hat. Bishops, archbishops, monsignors, wear clothing indicating their dignity. Priests, monks and nuns wear special clothing and it gave them a dignity that once again was communicating a spiritual language.

I recall my grief when I was told (in the wake of Vatican II) that several priests had said Mass in beach clothing on a very hot day… (To this day, I hope it was a nasty rumor.) I was very impressed when Rosalind Moss (now Mother Miriam of the Lamb of God) wrote that, even though a Jewess, far away from the faith, she was distressed after Vatican II when she noticed that many nuns gave up their habits.

Even though knowing nothing about the habit’s symbolism, she, hungry for God, perceived a message that, alas, so many Catholics have totally lost. She could never have suspected that the Hound of Heaven was already pursuing her.

A vestment transmits a message that we, blinded by secularism, no longer perceive. Throughout the Bible, the clothing one wears is indicative of dignity and rank.

When the prodigal son came home, the first thing that his father did, before feeding his starving child, was to give him “the first robe, that is the robe of innocence” (Gueranger, Saturday, the Second Week of Lent, p. 244). It should be our great concern to have the proper garments when invited to the King’s wedding. Let him who has ears to hear, hear.

Facebook Comments