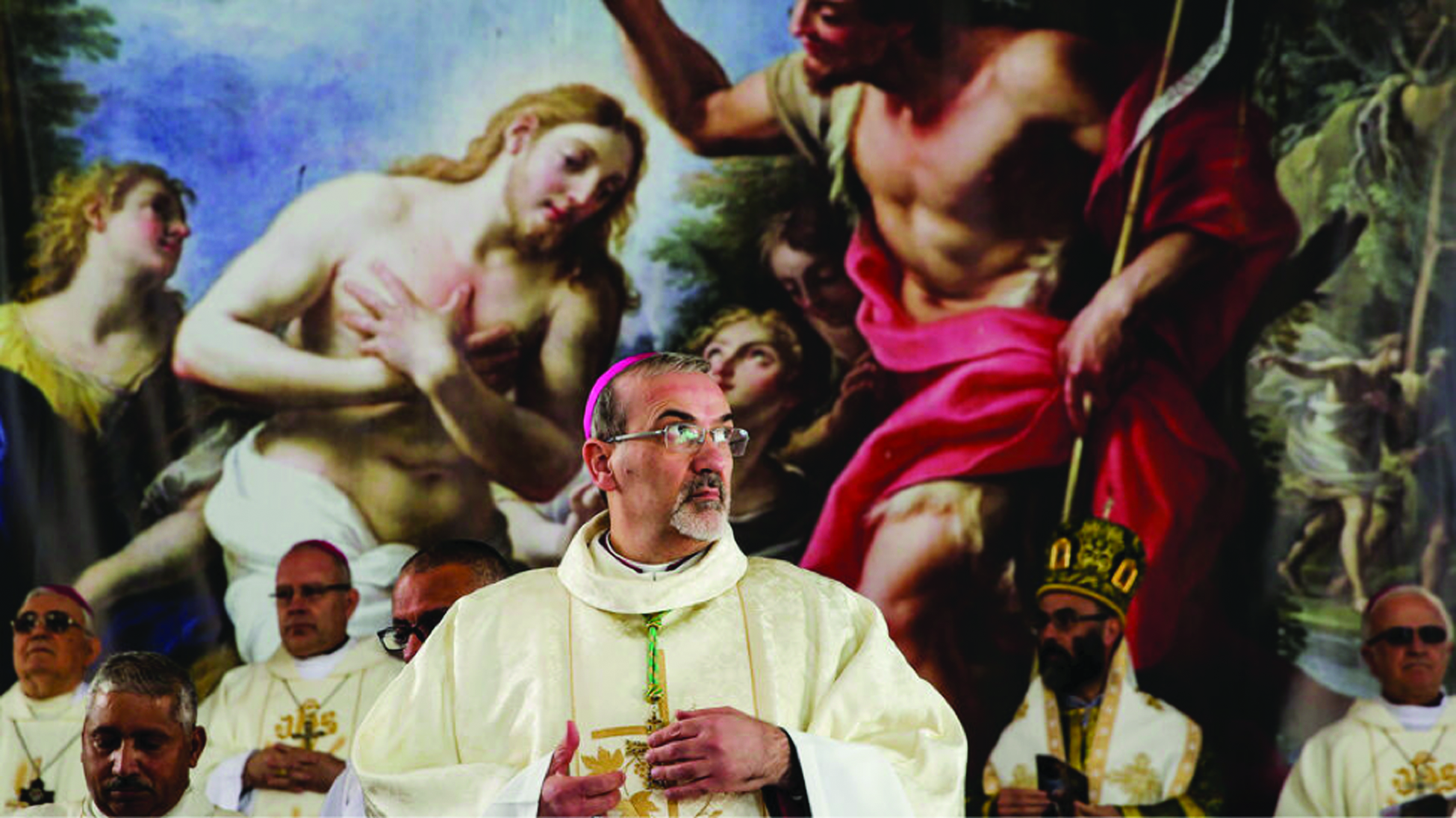

Clergy process at the start of the closing Mass of the Synod of Bishops for Africa in St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican Oct. 25. (CNS photo/Paul Haring) (Oct. 26, 2009)

Pope Francis traveled to Africa November 25-30, bringing a message of hope and reconciliation to three nations which continue to experience exploitation, violence, and even war: Kenya, Uganda and the Central African Republic. But he also acknowledged something Africa has to offer to the world, what he called “wisdom and spiritual values… that are the very soul of a people.”

His predecessor Pope Benedict XVI, at the Special Assembly for Africa of the 2009 Synod of Bishops, referred to Africa as “the spiritual lung” of the world, saying that “the acknowledgment of the absolute Lordship of God is one of the salient and unifying features of the African culture.”

There had been many concerns that the Pope’s trip to Africa might face difficulties, even that he might be harmed in a terrorist attack. But the Pope went everywhere, unafraid, including meetings with Muslims, and everywhere he went he preached peace and reconciliation. Finally, in the Central African Republic, he opened the Holy Year of Mercy a week before opening it in Rome, as if to say “the Year of Mercy begins in Africa.”

Three Wise Men from Africa

African cardinals Sarah, Njue and Napier bring their distinctive gifts to the universal Church

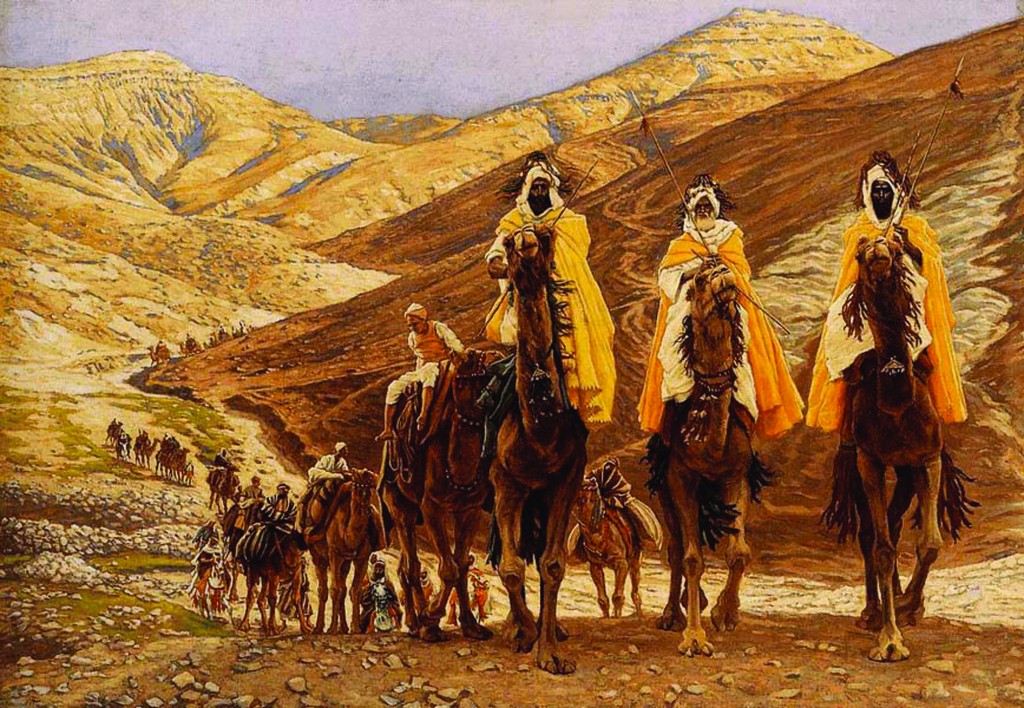

They came to worship the Christ Child and to lay before Him their gifts…three Wise Men from the East, who sought the face of their Creator and wished to give to Him of themselves, in gratitude and praise…

So today, three wise men of Africa, in seeking to worship the same Christ, bring their own gifts to help and enrich His Mystical Body, the Church — Sarah, of Guinea; Njue, the Kenyan; and Napier, of once-segregated South Africa — and their own vigorous, growing flocks.

Pope Benedict XVI, at the Special Assembly for Africa of the 2009 Synod of Bishops, referred to Africa as “the spiritual lung” of the world. And he explained this metaphor in terms of African culture; specifically, the continent’s almost universal recognition of the Creator, and reverence for His handiwork, the family.

The acknowledgment of the absolute lordship of God is one of the salient and unifying features of the African culture. Naturally in Africa there are many different cultures, but they all seem to be in agreement on this point: God is the Creator and the source of life. Now life — as we well know — manifests itself primarily in the union between the man and the woman and in the birth of children; this is a divine law, written in nature and thereby stronger and more prominent with respect to any human law, according to the clear and concise assertion by Jesus: “What God has united, human beings must not divide” (Mk 10:9). First of all the prospect is not a moral one: it concerns, before duty, the being, the order inscribed in Creation.

James J. Tissot, “Journey of the Magi” (1894), Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneopolis, Minnesota, USA

These three African cardinals are proving themselves determined to continue and even expand the role of Africa which Pope Benedict underscored as shaping and fostering the spiritual dimension of life in the twenty-first century — teaching the world to breathe, as it were, with the life-giving breath of the Spirit of God…

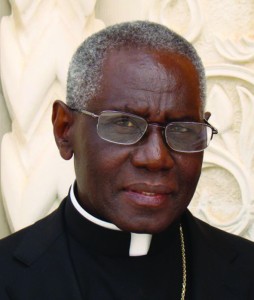

Cardinal Robert Sarah of Guinea:

“I feel wounded in my heart as a bishop in witnessing such incomprehension…”

Though he was not a formal member of this October’s Synod on the Family, Cardinal Robert Sarah, 70, was one of 11 cardinals who published a book in defense of traditional pastoral care of marriage before last year’s preparatory Synod on the Family; he also signed a letter to the Pope expressing “concerns” about this year’s Synod. As Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, he is keenly aware that he is in a position, like no other prelate, to explain the Church’s understanding of its own sacramental disciplines regarding marriage — in opposition, in some cases, to other members of the clergy, even other cardinals, who appear to contest that understanding.

Robert Cardinal Sarah

Cardinal Sarah laments what he calls “incomprehension of the Church’s definitive teaching on the part of my brother priests” in a recent article he penned for the French magazine L’Homme Nouveau. He goes on to say, in a section entitled “The Magisterium of the Church, This Unknown Terrain”: “I cannot allow myself to imagine as the cause of such confusion anything but the insufficiency of the formation of my confreres.” The “confusion” of which he speaks encompasses subjects like the origin, meaning and authority of doctrine — such as that defining the indissolubility of marriage — which he elucidates with reference to Vatican II documents like Lumen Gentium and Dei Verbum. “The position of the Church…is not a matter of the judgment of the majority,” says the cardinal. It is rather a “unanimity,” he says, of supernatural discernment of the entire People of God, in union with the bishops, “exercised under the guidance of the sacred teaching authority” (Lumen Gentium no. 12).

Cardinal Sarah also addresses the claim that “thousands of priests do not hesitate to give Communion to all,” including those in a publicly known state of habitual adultery due to divorce and civil remarriage, saying it represents “unequivocally a premeditated complicity and profanation of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Jesus.”

And he offers a retort to those, including one Western missionary priest, who dispute his description of the African family as one which today remains “stable, solid and traditional”: “I don’t know what African country and diocese this priest is talking about. But in Western Africa…. in the pure tradition of our ancestors, marriage is monogamous and indissoluble.”

Confusion abounds in liturgical matters as well, asserts the cardinal in a June 2015 issue of L’Osservatore Romano. Citing the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy from the Second Vatican Council, he says, “An excessively quick reading and above all, a far too human one, inferred that the faithful had to be kept constantly busy. Contemporary Western mentality formed by technology and bewitched by the mass media, wanted to make the liturgy into a work of effective and profitable pedagogy… They believe that participation is favored in this manner, whereas in fact, the liturgy is being reduced to a human game.”

In fact, says Cardinal Sarah, the correct notion of “participation” may be quite the opposite:

“This is the ultimate meaning of the key-concept of the Conciliar Constitution: participatio actuosa [active participation]. Such participation for the Church consists in becoming the instrument of Christ the Priest, with the aim of sharing in His Trinitarian mission. The Church takes part actively in the liturgical action of Christ in the measure that She is His instrument. In this sense, to speak of ‘a celebrating community’ is not devoid of ambiguity and requires prudence. (Instruction Redemptoris sacramentum, n. 42) ‘Participatio actuosa’ should not then be intended as the need to do something. On this point the Council’s teaching has frequently been deformed. Rather, it is about allowing Christ to take us and associate us with His Sacrifice.”

Likewise, Cardinal Sarah defends elements of liturgical tradition like orientation to the East; restriction of the sanctuary, clearly defined by its architecture, to divine worship; the wearing of sacred vestments; and the use of Latin. Yet he cautions that “those celebrating according to the ‘usus antiquor’ do so without any spirit of opposition,” reminding us that “it cannot be an occasion for laceration among Catholics.”

Cardinal Sarah’s article in L’Homme Nouveau was actually written in answer to objections he received after publishing his 2014 book God or Nothing: A Conversation on Faith, in which he discussed the causes and consequences of a society — particularly Western society — that “forgets God.”

Pope Emeritus Benedict, in a letter to the cardinal, had this to say about the book: “I have read Dieu ou Rien (God or Nothing) with great spiritual profit, joy, and gratitude. Your testimony to the Church in Africa, to its suffering during the time of Marxism and to a dynamic spiritual life is of great importance for the Church, which is somewhat spiritually weary in the West. All that you have written concerning the centrality of God, the celebration of the liturgy, the moral life of Christians is particularly significant and profound.

“Your courageous answers to the problems of gender theory clear up in a nebulous world a fundamental anthropological question.”

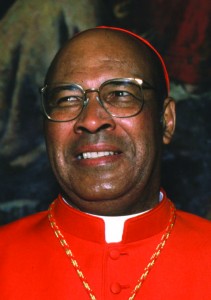

Kenyan cardinal John Njue navigates issues from domestic terrorism to homosexuality

Four gunmen associated with al-Shabaab, an Islamic extremist group based in neighboring Somalia, mowed down 149 people, mostly students, in an April 2 assault on Garissa University in Nairobi. In the aftermath, the Catholic Archbishop of Nairobi, Cardinal John Njue, 71, urged his flock to forgive the assailants, and also expressed hope that the Garissa attack would become a “moment of re-examination” of a government response deemed on many sides to be slow and ineffective.

24.11.2007 Vaticano. Visite di Cortesia ai nuovi Cardinali. Card. John Njue, Arcivescovo di Nairobi (Kenya).

“We pray, then, for all those who are concerned with this,” he said. “We are not dealing with animals, but with human beings…. If this were to happen to them, I don’t think any of them would be very joyful.”

In response to the attack, the Kenyan government, led by President Uhuru Kenyatta, launched air strikes on suspected militant positions in Somalia, and froze bank accounts of suspected terror financers.

For his part, Cardinal Njue said, after praying with families of the slain, “Let us pray for them [the attackers], that they may come to a point of undergoing a metamorphosis” in which they realize “they are dealing with life.”

A participant in the 2015 Synod on the Family, Cardinal Njue was asked, along with his brother bishops, to examine the role of compassion in another context — that of the Church’s pastoral care of homosexual persons.

Same-sex relationships are illegal in dozens of African countries and punishable by death in four, so Westerners frequently criticize what they perceive as unjustifiably harsh African attitudes toward homosexuality. But Cardinal Njue brushes off such criticism. “It’s not a question of criminalizing or condemning,” he says, “but we have every right to help the person understand that the way you are living is not how you’re supposed to be.”

“It is there in the Bible, “ he says. “It is clear… I think there is not much option. There are facts, such as the fact that God created humanity as Adam and Eve.”

“Whenever someone starts running away from their identity,” says the cardinal, “whatever they do will certainly not be the right thing.”

As for the controversial issue of delegating decisions about admittance of uncanonically married persons to Holy Communion, Cardinal Njue is convinced that “if we have a unified understanding of what the family is all about, then we have nothing to lose.”

On the contrary, “If we start operating one way in Africa and another way in Europe, and so on, then the image of the Church” — as one, holy, Catholic and apostolic — “is distorted,” he points out.

“If there is any form of diversion,” says the cardinal, “it can be very dangerous for the future.”

And the future is indeed on the mind of the cardinal, especially the future of the African family, in particular, as it is besieged by what Pope Francis has called the “ideological colonization” of the West. Wealthy and powerful Western governments and organizations habitually tie development assistance dollars to adoption of “family planning” initiatives or permissive laws relating to sexuality which are inimical to not only the Christian faith, but also to the traditional mores of many African cultures.

“They are trying to introduce family planning in the primary schools in Kenya,” he says. “You can be sure it is not something that is originating in Kenya, but is being pushed from outside, which is a pity.”

Njue also bristled at suggestions that the cardinals — a group of celibate males — have no right to discuss issues of sexuality and family life.

“I didn’t come from upstairs,” he says, “I was born in a family!” He went on to illustrate that his own experience of growing up in a family was tinged with pain and difficulty: when he was just a tot, he saw his father beat his mother. When he asked his mother why his father had behaved so, she told him to ask his father.

“I stayed a good distance away, but I asked him why he had beaten my mother,” Njue said. “I could hear his roar start, and by the time it finished I was a mile away.”

Yet from that point forward, Cardinal Njue said, his father was a “different man,” no longer violent with his mother.

South Africa’s First “Blessed”

Blessed Benedict Daswa (16 June 1946 – 2 February 1990), born Tshimangadzo Samuel Daswa, was a South African school teacher and principal. He was given the name of “Samuel” by his parents when he started to attend school, and assumed the name “Benedict” upon his conversion to Catholicism. After his conversion, he worked tirelessly as a Christian husband and father, a catechist and Catholic youth leader. After a period of extreme weather attributed by some to witchcraft, a local mob ambushed and murdered him when he refused to participate in their superstitious practices. His last words were, “Into your hands, Father, receive my spirit.” He was viewed as a martyr after his death and his martyrdom was confirmed in 2015 by the Vatican, paving the way for his beatification in Limpopo, South Africa, on September 13, 2015. Cardinal Angelo Amato, on behalf of Pope Francis, presided over the beatification Mass.

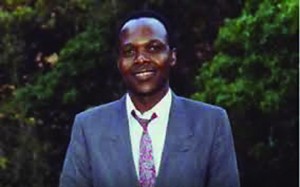

Cardinal Wilfred Napier highlights “the crucial role that the Church in Africa has to play, at a time when so many other churches are in a crisis of faith…”

Card. Napier Wilfrid Fox

Among the 13 Synod Fathers who signed a letter to Pope Francis, delivered in the first days of the 2015 Synod on the Family and expressing concern over modified Synod procedures, was Cardinal Wilfred Napier of Durban, South Africa. Cardinal Napier emerged as a leader among bishops who resisted possible sweeping changes in the Church’s pastoral care in sexual and family matters, emphasizing that the Church must be faithful to the prophets like John the Baptist, saying, as John did,

“‘You’ve got to repent, and these are the sins,’ and you name them as they are.”

Of the Synod deliberations, he said at one point, “There’s a lot of emphasis on using language that doesn’t offend, politically correct if you’d like.” He continued, “I’m not sure that’s the best way to be prophetic. It’s certainly a way to be more pastoral.”

Cardinal Napier notes that Pope Francis warned the Synod Fathers to avoid the two extremes of rigid traditionalism and radical liberalism — and has continued to reiterate and affirm the Church’s perennial teaching on the family, much to the delight of the African bishops, who as a bloc tend to approach doctrinal matters more conservatively than some of their European and American counterparts.

Asked in an interview with Zenit what his hopes for the Pope’s November visit to Africa are, Cardinal Napier mentioned three: “…the affirmation of the African Church for what it is and stands for in the worldwide Church, but also the re-affirmation of doctrines of the Church, especially in those areas where there is a concerted attack by governments and agencies mentioned above. A third expectation is that the Holy Father will hold up significant role models of Christian living, among whom we in South Africa are pleased to mention Blessed Benedict Daswa, recently beatified by the papal legate for the occasion, Cardinal Angelo Amato, SDB. We are still walking on air after witnessing that historic event! This visit gives Pope Francis an ideal opportunity to highlight the crucial role that the Church in Africa has to play, at a time when so many other churches are in a crisis of faith, of identity and of compromising with the world and its dogmas!”

Facebook Comments