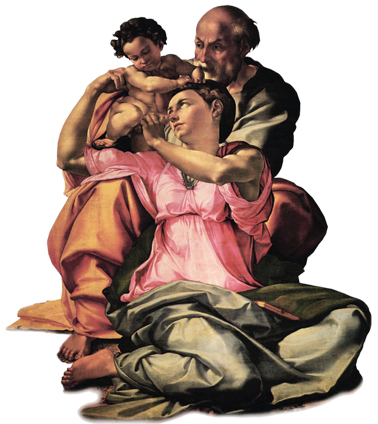

The Doni Tondo or Doni Madonna, sometimes called The Holy Family by Michaelangelo, circa 1507, oil and tempra on panel. 47-1/2 inches

A recent talk of the Pope’s raises central issues for our time. But is anyone listening?

I don’t quite know how to say this, so I’ll just be blunt: Pope Benedict is saying incredible things, yet no one seems to be listening.

He did it again on Saturday, two days ago.

Benedict is “standing watch on the ramparts” of our once-Christian society, and raising an alarm about terrible dangers he sees for humanity, but he is being, for the most part, ignored.

His words, in an age filled with noise, are uttered with passion and eloquence, but fall, echoless, into the cracks of silence between the major TV networks, which rarely give space on their programs to his words.

He should not be ignored. He is saying things worth taking very seriously indeed.

The Danger of “Gender Freedom” and the Need for Christian Unity

There are two main points he made in the past two days:

(1) on Saturday he spoke about the new philosophy of “gender” which views being a man or a woman as a totally changeable, individual choice; and he said this very “politically correct” theory, supported by so many in positions of power and influence today, presents a grave danger to humanity;

(2) on Friday and on Sunday (yesterday, at his noon Angelus address), he said that Christians must be more unified, that their divisions are a cause of scandal (precisely as we have been saying as we have launched our new Foundation, which I would again ask you to consider joining).

In a sense, these are the pre-eminent themes of this phase of Benedict’s pontificate: the reductionist new theory of gender as a choice, and the need for greater unity among Christians.

Why is Benedict hammering away at the issue of gender?

To put it bluntly: because he is frightened by the consequences for the human race that he sees on the horizon if this theory is not re-thought.

Ideas have consequences, and he believes strongly that the consequences of these “gender” ideas will be disastrous for mankind.

Like a watchman on the city walls, he is looking out, and he is seeing disaster approaching.

What disaster, precisely, does he see?

Benedict first refers to ideologies from past centuries which have brought much misery to man, referring to nationalism, National Socialism, Communism and also “unbridled capitalism”:

“In recent centuries, the ideologies which celebrated the cult of the nation, race, social class proved to be true idolatry, and the same can be said of unbridled capitalism with its cult of profit, with the resulting crisis, inequality and poverty,” he said.

But then he turned to a new “ideology,” the new theory of human “gender” as something not given, but chosen.

The danger, he says, includes that of a “technological prometheanism.”

The Danger of a “Technological Prometheanism”

Now, what does Benedict mean by this phrase? What he means is that modern science, with its great and increasing technological power, together with a “Promethean” attitude toward all limits, may lead us to terrible problems.

It is a dense, unusual phrase for a Pope, a phrase with no basis in Scripture (because Prometheus, of course, is not a character in Scripture, but a character of Greek myth).

Nevertheless, despite its newness and difficulty of interpretation, this may come to be seen as a “signature phrase” for this Pope, and for his diagnosis of our present predicament.

So what does Benedict mean when he warns of “technological prometheanism”?

Scientific Knowledge and Spiritual Knowledge

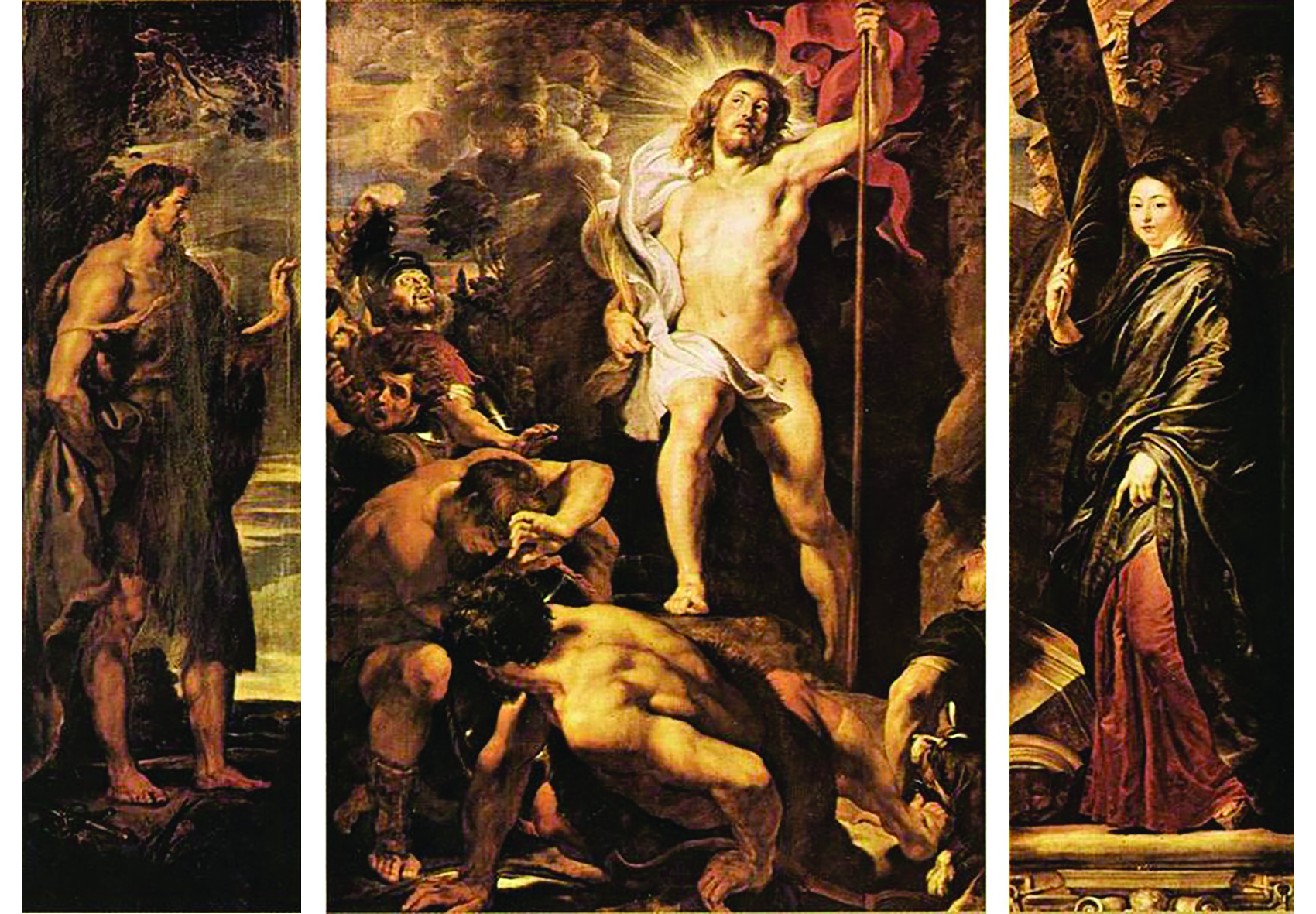

Prometheus Brings Fire to Mankind, by Heinrich Von Füger, 1817

In the Western classical tradition, the Greek mythological character Prometheus, who stole fire from heaven to give to mankind and then was punished for his theft by Zeus and bound forever to a mountaintop in the Caucasus by unbreakable chains, became a figure who represented human striving, particularly the quest for scientific knowledge.

Over time, and especially in the Romantic era, Prometheus was seen as the archetype of the lone genius whose efforts to improve human existence could also result in tragedy.

This is why British novelist Mary Shelley chose as the subtitle for her novel Frankenstein (1818) “The Modern Prometheus” — because there is a certain equivalence here between Prometheus and… Dr. Frankenstein.

The “modern Prometheus” is, in this sense, Shelley’s Dr. Frankenstein, who tries to go beyond the bounds of nature to create a creature different from any ever created by God — and ends up creating his monster: Frankenstein’s monster.

In the 1700s and 1800s, Prometheus came to be seen as the rebel who resisted all forms of institutional tyranny, epitomized by the pagan high god, Zeus — the Church, the monarch, patriarchal society.

Indeed, the Romantics drew comparisons between the Greek Prometheus and the spirit of the French Revolution… and between Prometheus and the Satan of John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

Yes, in this restricted analogy, to be Promethean was to be Satanic, Luciferian.

In short, Prometheus was the one who, rebelling against God, went beyond all the bounds set by God, seeking limitless freedom.

It is striking, however, that many of us (perhaps all of us?), have a certain sympathy for Prometheus. As the person who desires to surpass all limits in a search for total freedom, he seems somehow admirable. Because most humans, perhaps all humans, wish to be as free as possible, freedom is something desirable, something good; its antithesis, slavery, is something abhorrent, something evil.

But, as Christ said, “the truth shall set you free” — the difficulty is to grasp, to comprehend, the truth. For humans, our wonderful intellects darkened by passion and sin, to seek, to find, to grasp, to embrace the truth is often a difficult task, filled with pitfalls. We often do not know our own truth. And this can mean that, in a desire to be free, we embrace false paths, untrue paths, that lead us to sorrow.

And that is precisely what Benedict warned on Saturday.

The danger is that we have an untrue anthropology, and so an untrue understanding of what it means to be human, and so also of… what it means to be free.

“From the union between a materialistic view of man and the great development of technology an anthropology that is essentially atheist has emerged,” Benedict said (emphasis added). “It presupposes that the man is reduced to autonomous functions, the mind to the brain, human history to a destiny of self-realization.”

Here Benedict is warning about reductionism (“the man is reduced…”).

Reductionism is always in some sense “untrue” because it “reduces” the complexity of phenomena in order to “simplify” and so “comprehend” the phenomena.

It may seem as if the mind may be reduced to the brain, to the cells, to the electronic pulses of cells; it may seem that we can trace one emotion to the front of the brain and another to the back; but will the dissection of every single brain cell — Benedict is asking — ever finally locate “me”?

A gay couple during a demonstration in New York.

There is something in personhood which transcends, which cannot be reduced to, the material.

But our modern “science” (which is reductionist) denies that it cannot find “the person.” It says we simply haven’t yet the tools to go into every cell, to discover those cells where “the person” is hidden. Our “science” (and the Pope in a moment will call this science “Promethean”) mocks a man as a stubborn know-nothing if he claims he is somehow not material in his essence; that, science says, is to be excluded, for all things are material…

(This is what it means to live in an age when the dominant ideology is materialism.)

The Pope goes on: “In the perspective of a man deprived of his soul and therefore of a personal relationship with the Creator, what is technically possible becomes licit, each experiment is acceptable, any population policy permitted, any manipulation legitimized. The most dangerous pitfall of this line of thinking is in fact the absolute good of man: man wants to be ab-solutus, freed from every bond and every natural constitution.”

These words are stunningly powerful. Benedict is saying that it is when man wishes to be “absolute” (without God, without anyone telling him anything at all) that he finds himself at a total dead end and faces loneliness and… despair.

This, he said, “is a radical negation of man’s created and filial being, which results in a dramatic solitude.”

And Benedict warned that “we must never close our eyes to these serious ideologies… It is in fact a negative pitfall for man, even if disguised by good sentiment in the name of an alleged progress, or alleged rights, or an alleged humanism.”

These are just a few reflections, offered as a possible help to readers of the Pope’s words.

His words are so dense and rich that they deserve many more pages of reflection. But here is what the Pope said. I will let his words speak for themselves.

Facebook Comments