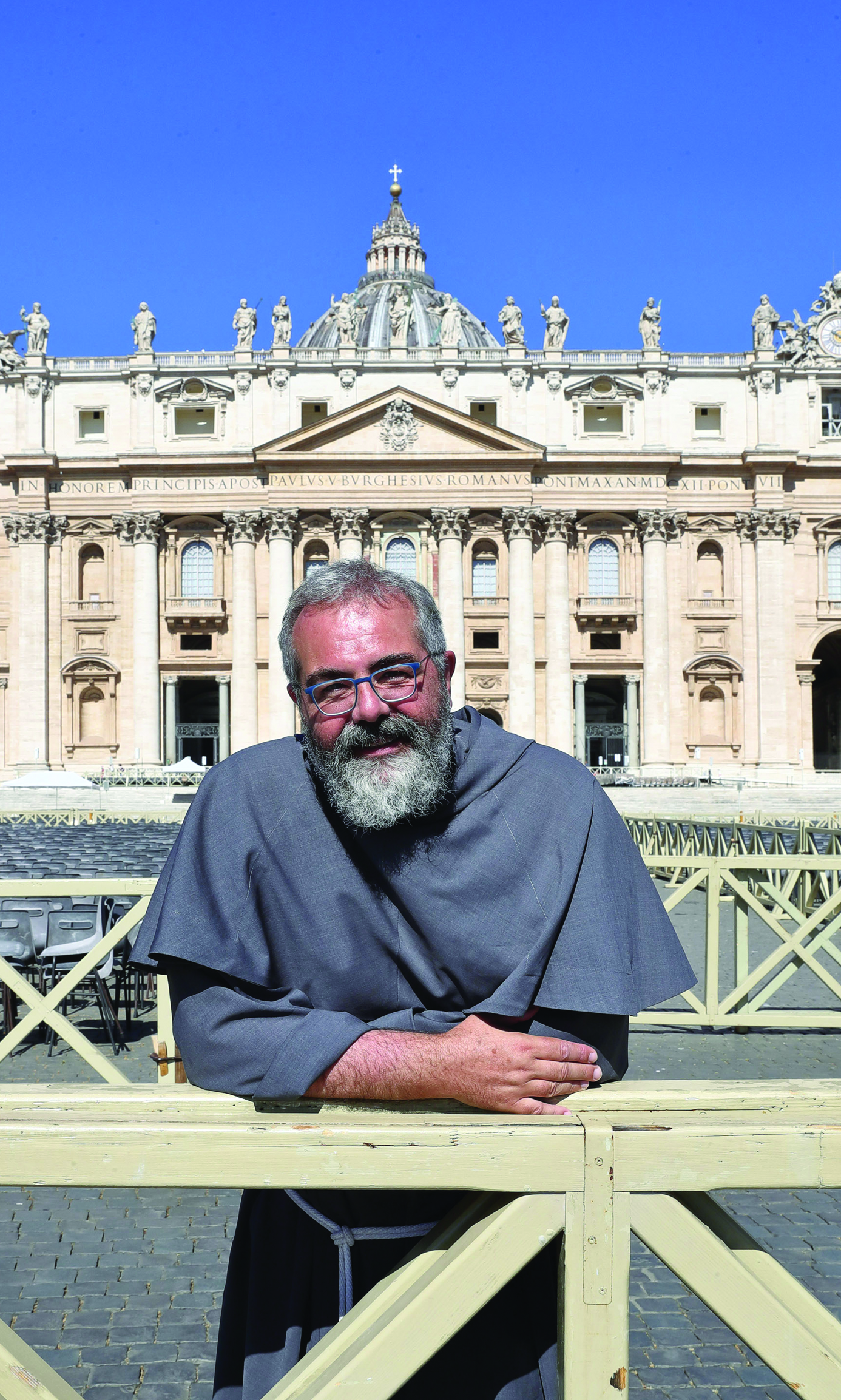

Archbishop Konrad Krajewski, Vatican Almoner, in his office.

Vatican Almoner Monsignor Konrad Krajewski, the hands-on extension of Pope Francis’ personal charity.

Monsignor Piero Marini, Pontifical Master of Ceremonies, called Monsignor Konrad Krajewski to work in the Vatican in 1998. They had met long before, in June 1987: during John Paul II’s third journey to Poland Konrad Krajewski, at the time a seminarian, had been entrusted with the liturgical aspects of the Pope’s visit to his hometown Łodz. Monsignor Marini was surprised that this task was being carried out by such a young man who had not yet been ordained. The Mass organized by Krajewski has gone down in history for a funny thing: the Pope wanted to be pictured with all the children attending Mass who were to make their First Communion, but there were 1500! Anyway, everything worked out, and Monsignor Marini still remembers this extraordinary event. John Paul II’s attention, on the other hand, was attracted to the thick black hair of the young master of ceremonies.

Msgr. Konrad Krajewski during Pope Francis’ Apostolic Journey to Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) on the occasion of the 28th World Youth Day (22-29 July 2013).

After being ordained in 1988, Krajewski left for Rome to study as a liturgist at the Pontifical Liturgical Institute Anselmianum; he obtained his doctor’s degree from the University of St. Thomas “Angelicum.” He returned to his hometown in 1995 to work as master of ceremonies for archbishop Władysław Ziołek while teaching at the seminary. In 1998 his Archbishop received a letter from Monsignor Marini asking him to “lend” his master of ceremonies to the Vatican for three years, that he might be employed in the preparations for the Year 2000 Jubilee. So at 35 Father Konrad found himself at the Office of Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff. He was scared not so much of dealing with the liturgy as of coping with office work which was now part of his task. He soon got in tune with his superior: what he liked about Monsignor Marini was not just his professional competence, but first and foremost his human and spiritual qualities. A period of hard work began for Monsignor Krajewski: he became involved in the organization of the Pope’s apostolic journeys on the spot and all the events of the Holy Year. He made himself so appreciated that at the end of the third year he did not return to Poland, but stayed in the Vatican, also because John Paul II, confronted by an ever-growing number of mobility problems, needed someone like him. On the other hand, living beside John Paul II, Krajewski learned day by day what priesthood is about. First of all, he learned that a priest must always be in contact with God, he must pray to be perceived as the image of God. In this Monsignor Krajewski tried to imitate the Pope. He once said that before entering the confessional (he hears confessions from 3 to 4 p.m. every day) he prays for those about go to confession and after that he does the same penance as the one he has imposed on his penitents.

Msgr. Konrad Krajewski during Pope Francis’ Apostolic Journey to Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) on the occasion of the 28th World Youth Day (22-29 July 2013).

Monsignor Krajewski lived beside John Paul II for seven years till his death. Interviewed by L’Osservatore Romano, he once revealed the dramatic moments of the Pope’s death on 2 April 2005. “We were kneeling around John Paul II’s bed. The Holy Father was lying in semi darkness. The dim light of the lamp illuminated the wall, but you could see him well. When a few moments later the time came when the whole world would know, all of a sudden Archbishop Dziwisz stood up. He turned on the light thus interrupting the silence following John Paul II’s death. In a voice at once broken and surprisingly firm with his typical mountain accent, dragging out some syllables he began to sing: ‘We praise thee, O God, we acknowledge thee to be the Lord.’ The athlete who had skied and walked in the mountains now stood still. The actor had lost his voice. All his strength had failed him by and by. Though broken hearted and with a lump in our throats we resumed our singing. With each word our voice grew louder and more confident. The song ran as follows: ‘When thou hadst overcome the sharpness of death thou didst open the Kingdom of Heaven to all believers.’ With ‘Te Deum’ we praised God visible and recognizable in the person of John Paul II. In a way this is what those who met John Paul II during his pontificate experienced.” Monsignor Krajewski has also revealed that he dressed the Pope after his death with the aid of three male nurses who “kept on speaking with the Holy Father as though they had been talking to their father. Before putting him into his cassock, his alb and chasuble they kissed, caressed and touched him with love and reverence. Their attitude did not only show their reverence to the Holy Father; to me it was the timid announcement of a forthcoming beatification. Perhaps for this reason I never devoted myself to praying intensely for his beatification, for I had already begun to take part in it.”

When a few days later Monsignor Krajewski attended John Paul II’s funeral as master of ceremonies, he did not imagine that he would be lucky enough to prepare the solemn ceremony of the beatification of “his pope.” But this took place during the pontificate of Benedict XVI, whom he served till the end, but in this case the end coincided with the Pope’s resignation in February 2013.

Pope Francis laid hands on Msgr. Konrad Krajewski during the rite of episcopal ordination, which took place in St. Peter’s Basilica on September 17.

In his spiritual testament John Paul II asked the faithful to pray for him. Monsignor Krajewski took his request very seriously: since the Pope’s death he has been celebrating Mass at 7 a.m. every Thursday, first at his tomb in the Vatican Grottoes, then in St. Peter’s Basilica. With the passing of time this Mass has become a regular meeting for many Polish priests and faithful living in Rome, but for pilgrims too. Every Thursday afternoon Monsignor Krajewski celebrates Vespers in his apartment for priests, nuns, friends and acquaintances: after the prayer he sits at table with those he calls “my Thursday family.” Monsignor Konrad in fact is first of all a priest, not a clerk, albeit a Vatican clerk. When during the Year of Faith somebody asked him what must be done to reach people outside the Church, he replied: “We are useful for the Church when we are saints, when our behavior and lifestyle do not hide, but reveal God. If we live up to the Ten Commandments, God breathes in us and people realize this. Good is contagious.” In order to be a priest in the spirit of the Sacred Heart, Monsignor Krajewski began to take care of the poor and needy. In the evening he visited those sleeping under the porches of Via della Conciliazione (not all of them are bums) near St. Peter’s Square.

When he was involved in the preparations for the conclave in March, he did not know that Benedict XVI’s successor would be a callejero priest, a street priest who, even as a cardinal, left his home in the evenings to visit the poor to have dinner with them and share their plight. Nor did Pope Francis know at the start that one of his masters of ceremonies did the same things he used to do in Buenos Aires, but when he got to know, he did not hesitate to appoint him Papal Almoner: he announced his decision on 3 August last. The episcopal consecration of Konrad Krajewski took place in St. Peter’s Basilica on 17 September: the ordination Mass was officiated by Cardinal Giuseppe Bertello (amongst the co-officiators was Monsignor Ziółek, archbishop emeritus of Łodz, who ordained the young Krajewski 25 years ago), but the Holy Father arrived unexpectedly, vested with only a stole over his papal robes. To Monsignor Krajewski’s relatives he explained what the almoner’s role should be: “Look – said the Pope – these are my arms, they are limited in length. If we extend them with Konrad’s arms, we will be able to reach the poor all over Italy.” During the ceremony Monsignor Krajewski asked Pope Francis to call him Father Konrad, even though he is now an archbishop. One day the Holy Father said to him, referring to his request: “Should anyone call you Your Excellency, charge them € 5 as a tax for the poor. I too felt like calling you Your Excellency, but I haven’t got € 5 in my pocket!”

In those days a big tragedy occurred off Lampedusa Island, the destination of refugees from North Africa: a migrant boat carrying hundreds of people capsized. Pope Francis sent his almoner to Lampedusa immediately to show how close he was, not only to the survivors (he brought them 1600 phone cards so that they could stay in contact with their families), but also to the rescuers (the police divers were faced with the painful task of recovering the dead from the bottom of the sea). It was also Pope Francis who instructed Father Konrad on how to carry out his mission: “You can sell your desk, — you don’t need it. Don’t wait for people to come ringing. You need to go out and look for the poor.” The Pope’s Almoner has thus become an itinerant: he travels on a white Fiat Qubo, since a Vatican blue car might scare people off. The Pope wants Father Konrad to contact people directly, where they live, in canteens, hospices, rest homes or hospitals: this is Pope Francis’ method. Monsignor Krajewski sets the example: “If anybody needs money for a bill, I’d better go to their home if I can, so that they may understand that the Pope is close to them through his almoner; if anybody feels lonely or deserted, I must go and embrace them so that they may feel the warmth of the Pope, hence of Christ’s Church.”

Archbishop Konrad Krajewski, director of papal charities, helps distribute boxes of “spiritual medicine” in St. Peter’s Square after Pope Francis’ recitation of the Angelus at the Vatican Nov. 17 (CNS photo).

When he goes out at night visiting people in need, Father Konrad is assisted by Swiss Guards who do this as voluntary extra work. Their support is invaluable because physical strength, along with knowledge of foreign languages, is needed in some situations. The acts of charity of the Vatican Almoner are supported by donations and the sale of the well known Papal Blessing Parchments.

Seventeen calligraphers and 11 clerks work in the Vatican Charity Office (“not enough – says Father Konrad – considering the amount of work to discharge and of mail to sort out”). In 2012 the Vatican Almoner spent € 1 million on 6500 requests for help. Obviously the amounts given out are not large , € 200, 500 or 1000 (larger and long term charity works are handled by other offices). Donations to the Papal Almoner have considerably increased this year, no doubt a result of Pope Francis’ election. Yet everything is immediately spent on the poor, because, as the Pope says to Monsignor Konrad: “A current account is OK when it’s empty. Don’t invest or tie up anything: spend everything on the poor.” Needless to say, aid must be distributed with discernment: every application must be stamped by a priest to make sure it is authentic. Almost every day the Vatican Charity Office receives letters asking for help directly from the Pope; on top of each letter Francis might write: “You know what to do.”

On 28 November the rumor, traced to Monsignor Krajewski, spread that the Holy Father had sometimes sneaked out of the Vatican with his almoner to bring help and comfort to the needy. Of course this rumor was denied as ungrounded.

Anyway, being in part responsible for this false scoop, I would like to reveal what happened on that late November Thursday. The previous month I got an e-mail from a friend involved in the organization of courses for journalists at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross; these courses would feature meetings with outstanding members of the Curia and the Church. My friend wanted me to persuade Monsignor Krajewski to take part in the November meeting. It was to be an informal meeting, as is often the case, just a few journalists talking over a cup of coffee in a bar in Borgo without interviews. On these conditions Monsignor Konrad agreed to participate on the morning of 28 November. I could not imagine that the news of the private meeting would reach the Vatican Press Office and that more than 30 journalists would turn up at the restaurant on that Thursday. All of them recorded Monsignor Krajewski’s story, which lasted more than one hour, but, as he went on, he was often interrupted by the journalists’ questions. “If I say that I’m going out of the Vatican to visit the poor,” said Father Konrad, “there is always the risk that the Pope may want to join me. You know … he’s like this.” Hearing these words one of the journalists asked Father Konrad if that had already happened. “Next question, please,” was Monsignor Krajewski’s reply, but he soon added: “We soon realized that there were security problems: it is complicated. Anyway the Pope is like this, he does not take difficulties into account.”

The journalist from the ANSA Press Agency read into Father Konrad’s words an admission that something like that might have happened. Then he justified himself saying that Monsignor Krajewski had replied with a flat denial, which left room for different interpretations. Vice director of the Vatican Press Office and Monsignor Krajewski himself cleared everything up within the day. The latter said: “Of course the Holy Father would like to go out and meet the poor, but he’s never done so.” He would certainly like it because, as he said to his almoner: “You do the most beautiful job.” His words should give everyone food for thought.

Facebook Comments