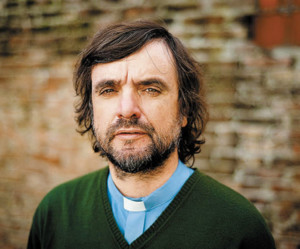

Padre Pepe.

He is “one of the men whom I respect the most and to whom I listen attentively, and not just because he is a priest,” Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio (now Pope Francis) said in 2010. “He is a man of God who does my soul and my spiritual life much good.” The man he was speaking about? Fr. Jose Maria Di Paola, 51, a priest of the slums of Buenos Aires, also known as “Padre Pepe,” as people in Buenos Aires call him. He has been a priest for 30 years and has spent much of this time in one of Buenos Aires’ Villas miserias, literally “Villas of misery,” the slums where the poorest of the poor live. For his lifelong witness of Christian courage and charity — and as a representative of all those who engage in such difficult ministries — we honor “Padre Pepe” as one of our “Top Ten” people of 2013.

Born into a middle-class family in Buenos Aires, Di Paola reached the decision for the priesthood in his adolescence, with the intention of “bringing children, young people, and the poor to God,” according to St. Francis of Assisi’s model of total dedication. He was named pastor of the Barracas slum in 1997, 10 years after his ordination to the priesthood. From then on, he was often visited by his bishop, Bergoglio, who was already speaking to him about the need to go out to the geographical and existential periphery.

There are roughly 20 of these crowded slums in Buenos Aires, often just a block or so away from gleaming high-rise office towers and luxury apartment buildings. “Villa 21” is the largest with a population of almost 50,000 people. The beating heart of Villa 21 is the parish of the Virgin of Caacupé, where Bergoglio appointed “Padre Pepe” as a parish priest.

In the relationship with these people, and in getting to know their stories, Padre Pepe could, in Pope Francis’ words, “touch the flesh of Christ.” Padre Pepe says, “One of the few things that Bergoglio advised us, not knowing anything about the rehabilitation of drug addicts, was to work directly with individual people, because each one has a different story and there is no recipe that works for everyone. Each person arrived with his wound, with his suffering, and when we spoke to Bergoglio about it, he told us that for us to approach them was like touching the wounds of Christ, seeing the face or the suffering flesh of Christ.”

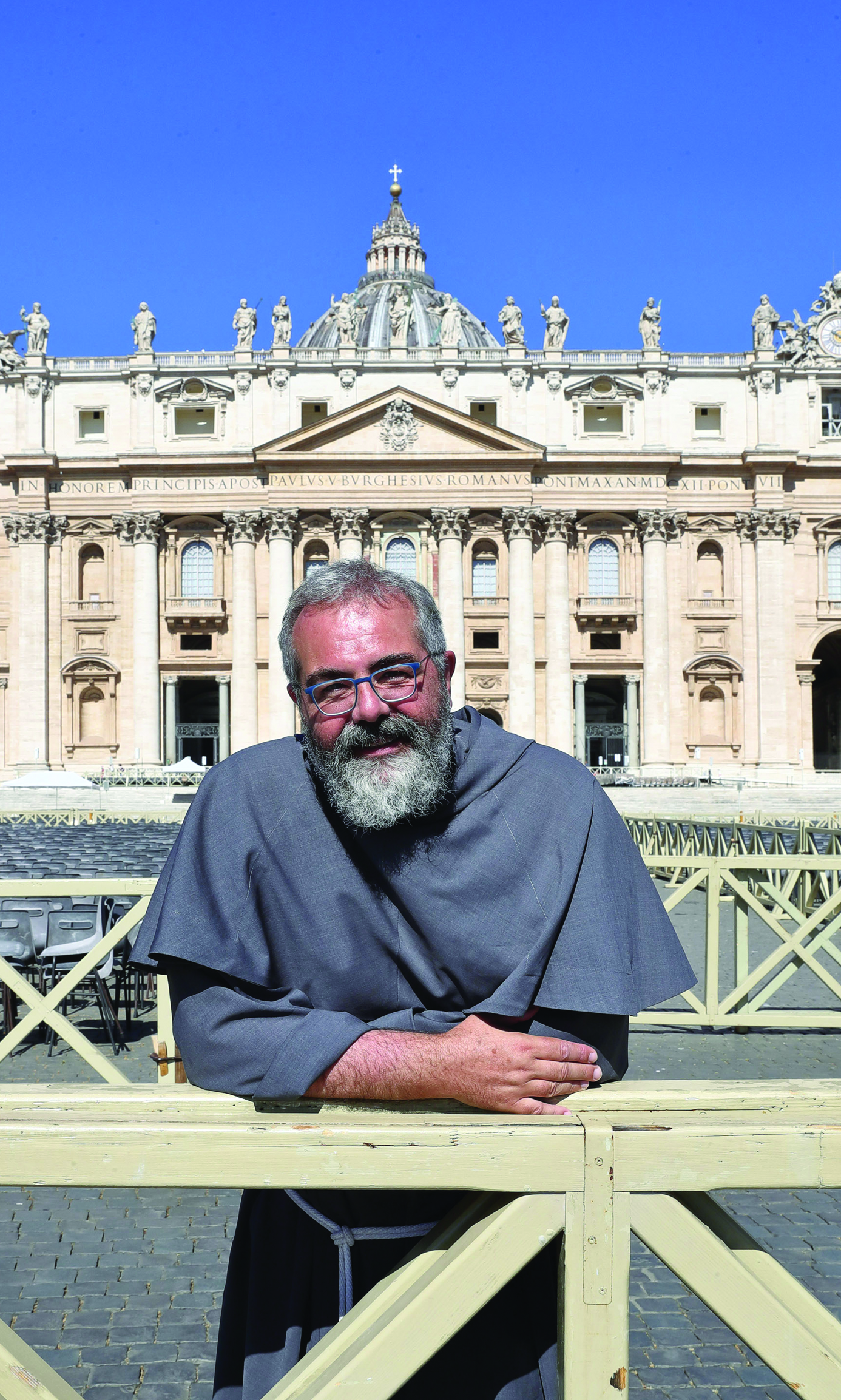

Pope Francis, as bishop, is seen celebrating Mass at the Villa 21-24 slum in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1998. Padre Pepe (without a beard) is the first one on the left.

The Pope knows what it means to fight alongside the poorest in order to regain the dignity trampled by drug traffickers and powerful people. “Bergoglio doubled the number of priests who exercised their ministry in the villas, because he wanted priests working in community, in each of these neighborhoods, so that the projects carried out would produce fruit. We did not use sociological analysis, but the Gospel,” Padre Pepe said.

Padre Pepe was sent to Villa 21 to share the lives of the people. The aim was to make the faith come alive, preaching and celebrating the sacraments while also working to prevent drug addiction and helping to reintegrate drug addicts back into society, educating the young and taking care of the old, providing job training, taking care of people’s lives. “I can testify to the beauty of so many cases of young people who felt welcome, found their faith and came out of their drug abyss because they felt loved by a Church that knew how to be close to them,” Padre Pepe has said.

Drug traffickers clearly didn’t like this. The first threats against Padre Pepe came in the spring of 2009. When more serious threats arrived from drug dealers in December 2010, then-Archbishop Bergoglio decided to move him to another parish north of the city. Now Padre Pepe ministers in another villa, continuing his work in the slums. “They threatened me on a Monday,” he said. “On Tuesday I went to Bergoglio. I told him the threat was serious. The very first thing he said was: ‘I would rather they kill me than any of you’…

“Bergoglio always encouraged us to go into the geographical and existential peripheries, but he did not just send us into the villas, he shared this experience with us,” Padre Pepe said. “He accompanied people and priests. He was close to us. This is why the only people who are not at all shocked at Pope Francis’ actions (since his election) are the poor people from the villas and former drug addicts. Bergoglio stood by their side more than he was close to any intellectual or academic circles. I can testify to the fact that those who lived in the villas felt that the archbishop was integrated in the daily life of the communities. He was a shepherd who physically visited our neighborhoods, reversing the perspective of a look, no longer facing the center of political and economic power of Buenos Aires, but looking toward the poorest suburb and the abandoned people.” He also said: “On one hand, Bishop Bergoglio invited the priests of his diocese to give value to the religiosity of people of the villas, and on the other hand, to have a different vision of the poor, to look upon them as people to learn from. That’s why they feel so close to him; he is a villero!”

“Padre Pepe possesses nothing,” then-cardinal Bergoglio told Silvina Premat during an interview he granted her for a book she was writing on Di Paola’s life. Bergoglio was referring to Padre Pepe’s capacity to not attribute the merit of his many and diverse works to himself.

In that “nothing,” Padre Pepe has found everything, and for this reason we honor him.

—Maria Pia Carriquiry Gomez

Facebook Comments