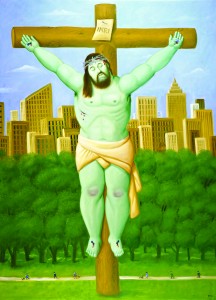

“The Crucifixion in Central Park”

“Art is a spiritual, immaterial respite from the hardships of life.” —Fernando Botero

Born in Medellín, Colombia, on April 19, 1932, Fernando Botero, whose signature style, also known as “Boterismo,” depicts overly rotund human figures both in his paintings and in his sculptures, is one of today’s most prolific and beloved artists. His works are on permanent display in Austria, Belgium, Chile, Colombia, Finland, Germany, Japan, Israel, Italy, Norway, Puerto Rico, Russia, South Korea, the United States, Vatican City in the Museums’ Collection of Modern Religious Art, and Venezuela. In the United States they’re in the collections of the Baltimore Museum of Art; the Birmingham Museum of Art; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden at the Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C.; the Hood Museum of Art, Hanover, New Hampshire; the Grey Art Gallery and Study Center at New York University, the Metropolitan Museum, MOMA, and the Guggenheim, all in New York City; the Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, Texas; the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida; Meadow Brook Art Gallery, Oakland University, Rochester, New York; M.H.K. Foundation, Milwaukee; Museum of Art, Pennsylvania State University; and the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence.

Botero, who long ago self-titled himself “the most Colombian of Colombian artists,” has had a peripatetic life between his native Colombia and Europe. Still today he spends only approximately one month a year in Colombia, residing in Paris, Pietrasanta in Tuscany, Monaco and Mexico.

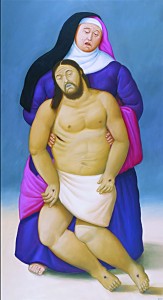

Mary Afflicted

Botero’s first trip abroad was in 1952. Thanks to the money from an award and the sale of some of his early works, Botero sailed to Europe on an Italian ship. His first stops were Barcelona and Madrid, where he joined the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando. In 1953 he spent the summer in Paris, before moving for the next five years to Florence where he joined the local Academy of Fine Arts. There his work was strongly influenced by the painters of the Italian Renaissance, particularly Piero della Francesca, Paolo Uccello, and Titian.

In 1958 Botero returned to Bogotà where was appointed as an art teacher at the National University’s School of Fine Arts. That same year he had an exhibition in Washington, D.C. where he sold all of his works on opening day. This exploit made him world-famous.

For example, as the website www.palermo.it tells us, “Botero is one of the few artists (if not the only one) who has had the privilege of exhibiting his works in some of the most famous streets and squares in the world, like the Champs-Élysées in Paris, Park Avenue in New York, the Paseo de Recoletos in Madrid, the Praça do Comércio in Lisbon, Piazza della Signoria in Florence, and even in front of the pyramids of Egypt.”

Although certainly appreciated for these sculptures of his “large people,” Botero is most famous for three cycles of social satire paintings. The earliest, dating to 2004, is a series of 27 drawings and 23 paintings dealing with the violence in Colombia from the drug cartels. He donated these works to the National Museum of Colombia, where they were first exhibited.

“The Kiss of Judas,” showing Botero’s self-portrait in the lower left-hand corner

The second, dating to 2005, is his Abu Ghraib cycle, based on reports of the United States army’s abusive treatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraqi War. “Beginning with an idea he had on a plane journey,” Wikipedia’s bio tells us, “Botero produced more than 85 paintings and 100 drawings in exploring this concept and painting ‘out of poison.’”

Like the cartel paintings, he did not sell any of these works, but donated them to various museums. First shown in Europe, they were exhibited in 2007 at the American University Museum at the Katzen Art Center in Washington, D.C. and at the Doe Library at the University of California’s Berkeley campus. A few had been shown a year earlier at the Marlborough Gallery in New York.

The third cycle, Via Crucis: La Passione di Cristo or The Way of the Cross: The Passion of Christ, is now on display in Rome’s Palazzo dell’Exposizione on Via Nazionale through May 1, 2016.

Painted in stunning colors and in various sizes between 2010 and 2011, the cycle consists of 27 oil paintings and 34 watercolors or drawings on paper. They show the influence by Van Eyck, Uccello, Rubens, Velázquez, Cézanne, and Picasso, and were first exhibited in Medellín, Botero’s birthplace, during Holy Week 2012 as part of the celebrations for his 80th birthday. Like the two previous cycles, he donated them, this time to the Museo de Antioquia in his hometown, but they’ve been on a world tour almost ever since. Before Rome, they were on display in Chile, the United States, Panama, and Portugal, and in Palermo during Lent of 2015.

As a child in Colombia, Botero was surrounded by paintings on Christian subjects, omnipresent in both public and private spaces. In a recent interview he explains: “The Via Crucis was the great theme of art up to the 16th century. It gradually began to disappear, and by the time of the French Revolution, it had practically disappeared. Today it is nonexistent. Perhaps that is why I became interested in it… I am not a religious person, but this theme has a beautiful artistic tradition. During the Renaissance, painters mixed daily reality with history: the Roman centurions are soldiers of the epoch in an Italian landscape. I took the same liberty to mix certain Latin American realities with the Biblical theme.” In fact, his “Roman centurions” are modern-day Colombian police and the landscapes of his paintings South American towns, except in one large canvas of the Crucifixion with Central Park and New York’s Upper West Side as the background. Later asked why he painted his self-portrait in The Kiss of Judas, he explained: “That was another tradition — to paint one’s own portrait in the midst of Biblical themes. Masaccio [appears] next to Jesus in the Brancaccio Chapel of Florence, Pinturicchio in his frescoes in Siena, and Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel’s Last Judgment, and so on. I put on my Sunday best to appear near Christ. It couldn’t have been any other way.”

Mary with Dead Jesus

Concerning the exhibition, its flier says: “What we see here is a crossroads where memories of his city, of his homeland, are strongly crisscrossed by forms of worship deeply ingrained in his culture and in his iconography. The soft features, the ideas and the forms that seem so stable are crisscrossed here by the upheaval in which grief and tragedy take shape, adopting the figurative language that is the hallmark of the Colombian artist’s work, yet without abandoning his uniquely distorting gaze. We should consider these pictures, in which drama now sweeps into the picture, as a new manifestation in which internal transformations can be identified that enrich and expand his work. Here irony is replaced by compassion, a reflection on poetry and on tragedy, on the intensity and the cruelty of Christ’s passion.”

In fact, although in all three cycles, his human figures are “fat people,” some even in similar poses, and torture is a common theme, nonetheless there is universality, a sense of forgiveness here that isn’t present in the other two cycles’ angry denunciation of violence.

Nonetheless in spite of the paintings’ beauty, perhaps due to the scarcity of explanations on wall panels, I left the exhibition perplexed and with several questions, kindly clarified in an e-mail from the exhibition’s curator, Nydia Gutierrez, also the chief curator of the Museo de Antioquia:

Why is Judas, and sometimes Christ’s flesh, painted green?

Nydia Gutierrez: This series is not a religious rendering of sacred history… The inclusion of one theme or another is always subordinate to Botero’s pictorial needs. He refers to the Via Crucis and to any other of his cycles as pictorial endeavors; therefore, depending on his pictorial challenges and needs, the artist used colors, balance, composition, and atmosphere at will.

Christ Dead

The artwork, both in the painting section and in the drawing section, is not hung in the chronological order of Holy Week’s events. Why?

Gutierrez: Botero chose to paint some episodes of the Via Crucis more than once and not to include others. Therefore, the layout is not a chronological installation of Holy Week’s events.

The 27 paintings and 34 drawings on view in Rome comprise the total number of artworks he donated to the Museo de Antioquia in 2012 as his Via Crucis cycle. He has not done additional works on this subject.

Did he ever explain the choices of which events he painted?

Gutierrez: He’s always said that he painted the scenes he found more appealing from a painter’s perspective.

Facebook Comments