Angelo Sodano’s book “Chiesa e riforme, una chiesa de amare”.

The Vatican Press has just published, in Italian, a small but quite interesting book by Cardinal Angelo Sodano on the topic of Church reforms in general and Curial reforms in particular. Given the emphasis on Church and Curial reform in this first year and a half of Pope Francis’ pontificate, and given the position of Sodano — dean of the College of Cardinals, and now 86 years of age — this book could not be more timely, and offers a privileged glimpse into how a leading, influential Churchman is viewing the process Francis has launched and is attempting to bring to completion. The volume contains the text of a lecture given on March 20 this year at the headquarters of the influential Italian Jesuit journal, Civiltà Cattolica. (The book also contains a text by the late Jesuit theologian and cardinal, Henri de Lubac, dedicated to the theme of the Church as our mother.) It would be useful to have this book translated and published by an English-language publisher.

Here we publish excerpts from the volume, entitled Chiesa e riforme: Una Chiesa da amare (The Church and Reforms: A Church to Love), Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2014, pp. 73, € 10.

“Concretely, there is a first reform to carry out in the Church. And that is, a continuing internal reform of her children. It is a work of continual purification, to enable her to better correspond to her vocation and to give witness to her faith before the world”.

By Cardinal Angelo Sodano

In any dictionary, the concept of “reform” indicates the act intended to bring a given reality back to its earlier “form.” It is, therefore, a term different than “transformation” or “deformation.” The form, as is known, is the shape in which a certain reality appears to us. If the form is brought back to its primitive beginning, we find ourselves faced with a reform.

Applying this criterion to the reforms to be made in the Church, it will be necessary, then, to bear clearly in mind that in the Church is an original part willed by Christ that, therefore, cannot be touched. The case is different when we consider the human aspects of the Church, for which reforms are possible and, in some cases, required to be made.

Concretely, there is a first reform to carry out in the Church. And that is, a continuing internal reform of her children. It is a work of continual purification, to enable her to better correspond to her vocation and to give witness to her faith before the world. This is what Pope Paul VI said in 1975, in his famous Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii nuntiandi: “It is by her conduct, by her life, that the Church in the first place will evangelize the world, that is to say, through her living witness of fidelity to the Lord Jesus, through her poverty and detachment, through her freedom in front of the powers of this world, in a word, by the witness of her holiness” (cf. ibidem, n. 41).

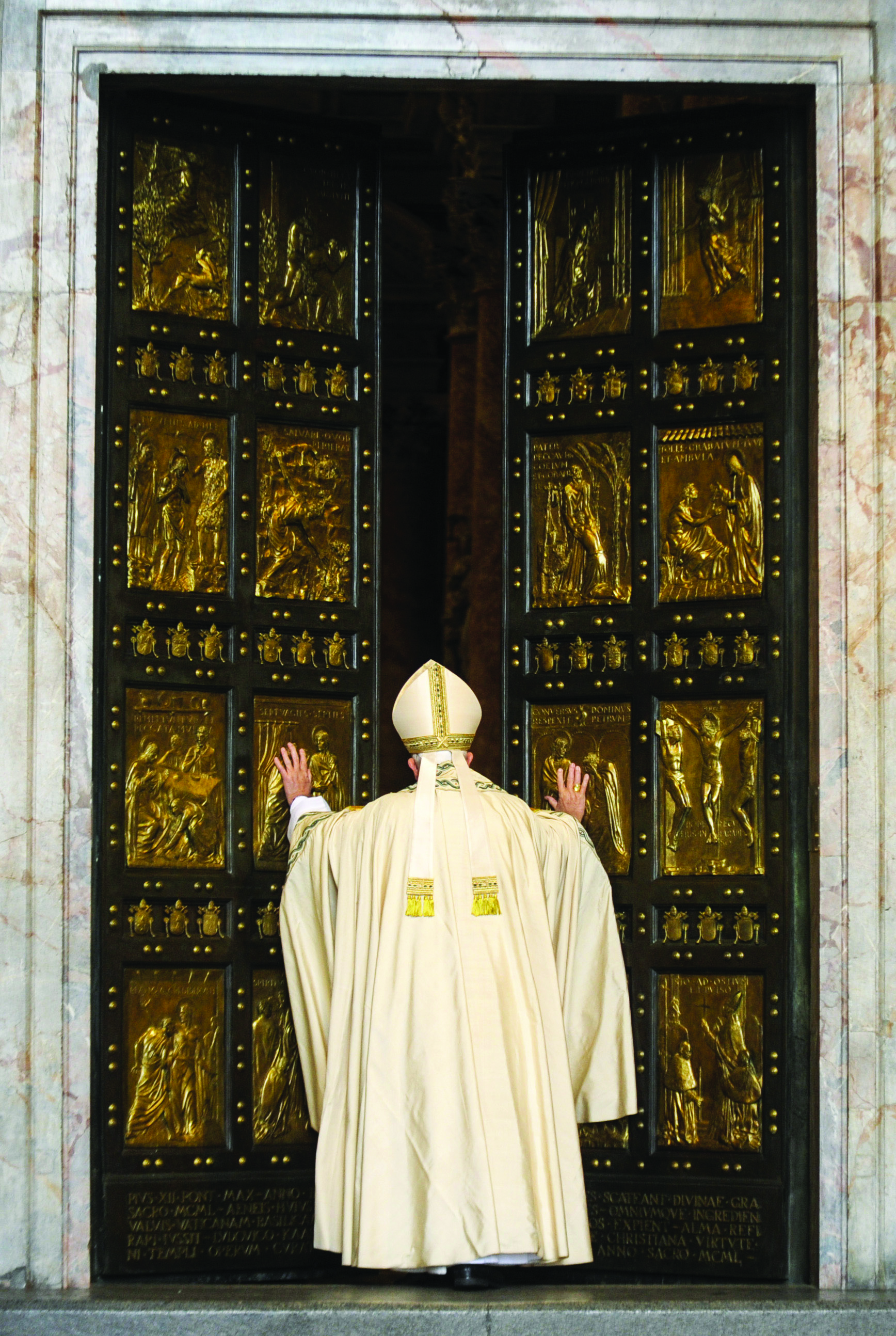

Pope Francis, placed by the Holy Spirit to govern the Holy Church of Christ at this present stage of her history, has repeatedly returned to this point, that a continual interior reform of the Church is essential. Suffice it to mention what he wrote in his first Apostolic Exhortation, Evangelii gaudium of November 24, 2013, at the conclusion of the Year of Faith. There, the Pope spoke, in fact, of the need for an urgent renewal of the Church, starting from each individual Christian, then affecting the whole Church and the reform of her structures (Evangelii gaudium, nos. 25-27).

In fact, every man is a sinner and in need of conversion. The Lord spoke of the need for this conversion from the very beginning of his public life, saying, “The Kingdom of God is at hand: repent and believe the Gospel” (Mark 1:15).

In the history of the Church, the saints have contributed with words and deeds to this work of the spiritual renewal of their contemporaries. It is enough to think of the “Poverello” (“Little poor man,” St. Francis) of Assisi, from whom the current Successor of Peter wished to be inspired, taking his name as his own.

For his part, St. Thomas Aquinas in his Summa Theologica recalled that the very life of Christ was a reform of the whole human race. His are the famous words incarnatio Christi est reformativa totius humani generis, “the incarnation of Christ is the reform of (or ‘reformative of’) the whole human race” (ibid., IIIa, q. 2A, Art. 11).

Well known also is the thought of St. Ignatius of Loyola about the reform of the Church, as we have recently read in a thoughtful article in Civiltà Cattolica by Father Enrico Cattaneo. The title of the article is precisely this: “The reform of the Church according to St. Ignatius of Loyola” (cf. Civiltà Cattolica, November 16, 2013). There we read that for St. Ignatius the reform of the Church was not so much a matter of her structures as it was a matter of the lives of her members, her pastors and her faithful. Precisely for this reason the holy founder of the Society of Jesus gave life to the instrument of spiritual exercises.

If we look, then, at that 16th century, the century of the reform of (Martin) Luther, we must also say that this was also the century of the Council of Trent. It was at that Council that the voice echoed of those who recalled that “you should not reform the Church by means of men, but reform men by means of the Church.” The phrase is generally attributed to Pope Paul IV. In any case, it shows well the concept of reform that the Council intended to promote in the Church, et capita in membris (“in head and in members”). This was the true reform of the Church, not the one proposed by Luther. In fact, he was more a deformer than a reformer of the Church, without entering into the question of what his real intentions were.

At this point of our reflection, the desire arises spontaneously to know the deeper reason that leads the Church to periodically review its structures of service to the community.

A first answer was already given by the Apostle Paul, writing to the Christians in Corinth who questioned his apostolic dynamism. He reminded them that it was the love of Christ which led him to intervene in that community that he himself had founded. Those inspired words, “Caritas Christi urget nos,” the love of Christ impels us, became over the course of centuries the inspiration of the apostolic activity of many saints.

The reforms in the Church do not come, then, from a pure desire to adapt to the times, but from an inner urge. It is the urge of a love for Christ and for his Church, that she may always be that “sign raised up over the nations,” in which the Prophet Isaiah saw already identified the Kingdom of God (Isaiah 5:26).

The reforms also do not come from a desire to indulge eventual pressures of public opinion or to adapt to trends in the world. Already the Apostle Paul invited the Christians in Rome not to adapt themselves to the spirit of the world, specifically telling them: “Be not be conformed to this world” (Romans 12:2). The love for Christ and for his Church leads the Christian to have a style of his own, made of meekness and humility, even faced with the need to denounce flaws or gaps in the action of her pastors. Love for the Church also leads the Christian to avoid the “bitter zeal and strife” mentioned by the Apostle James in his letter (James 3:11).

We Italians have the example given us by Blessed Antonio Rosmini who, in his great love for the truth and in his great spirit of charity did not have trouble speaking clearly of reform, in particular of the “Five Wounds of the Church” of his time. Animated by the a great ecclesial sense, in those stormy days of 1848, he saw a need to foster a stronger presence of the Church in the society of his time. True, some of his proposals seemed inopportune, but he accepted with great humility all the observations made to him. Time in the end dispelled every cloud. Today, for example, we see how contemporary is his appeal to treat the fifth of the “five wounds,” that is “subjection to the Church properties.” In the end, his invitation to make right use of the goods entrusted to the Church by the faithful, to assure her the necessary means to fulfill her mission in the world, is still valid today. Recently, a scholar of Rosmini, Bishop Nunzio Galantino, now secretary of the Italian bishops’ conference, wrote that Rosmini gave us an “ecclesiology of ecclesiastical property” (see Avvenire of February 12, 2014, “I soldi della Chiesa: da piaga a risorsa,” “The Church’s money: from plague to resource”). Among other things, Bishop Galantino had published in the past a critical edition of the work of the famous philosopher of Rovereto, namely The Five Wounds of the Church (Milan, San Paolo, 1997).

More vehement was certainly, in another historical context, the 14th century, another great figure of the Church, St. Catherine of Siena. With a bold program, she wanted to reform the Church, both by correcting some of her ministers from corruption, and by working to restore the Holy See to Rome, after Pope Clement V in 1309 had moved it to Avignon, and even trying to organize a crusade against the infidels! But reading her writings, we see how much Caterina Benincasa was in love with the Church. In particular, we see how much she loved the Pope, even calling him “O my Father, my sweet Christ on earth,” and how much she venerated priests, as we see in the 382 letters that have come down to us, and especially in the Dialogue of Divine Providence. Of course, the saint often spoke of reforming the life of the Christian community, but she was always thinking of an interior reform, “not with war but with peace and quiet, with humble and continual prayers, with the sweat and tears of the servants of God” (cf. Dialogue, DC. XV, LXXXIV).

In sum, the impetus for the activities of our saint was an ardent love for the Holy Church of Christ. In fact, her last words before she died were the following: “Hold for certain, my sweet little children, I spent my life in the Church and for Holy Church, which was for me an extraordinary grace” (Raymond da Capua, Life, III, 4). Not for nothing did Pope Paul VI in 1970 wish to declare her a Doctor of the Church, along with St. Teresa of Ávila, reformer of monastic life. In this context one could name many other men and women who for their apostolic zeal shone in the firmament of the Church, contributing to her renewal, along with the pastors of the Church.

Pope Pius XII said as much in a famous speech to the participants at the World Congress of the Apostolate of the Laity, in 1951: “In the decisive battles, sometimes the happiest initiatives come from the front line. The history of the Church offers us many examples.” (Acta Apostolicae Sedis)

(L’Osservatore Romano, May 22, 2014)

Facebook Comments