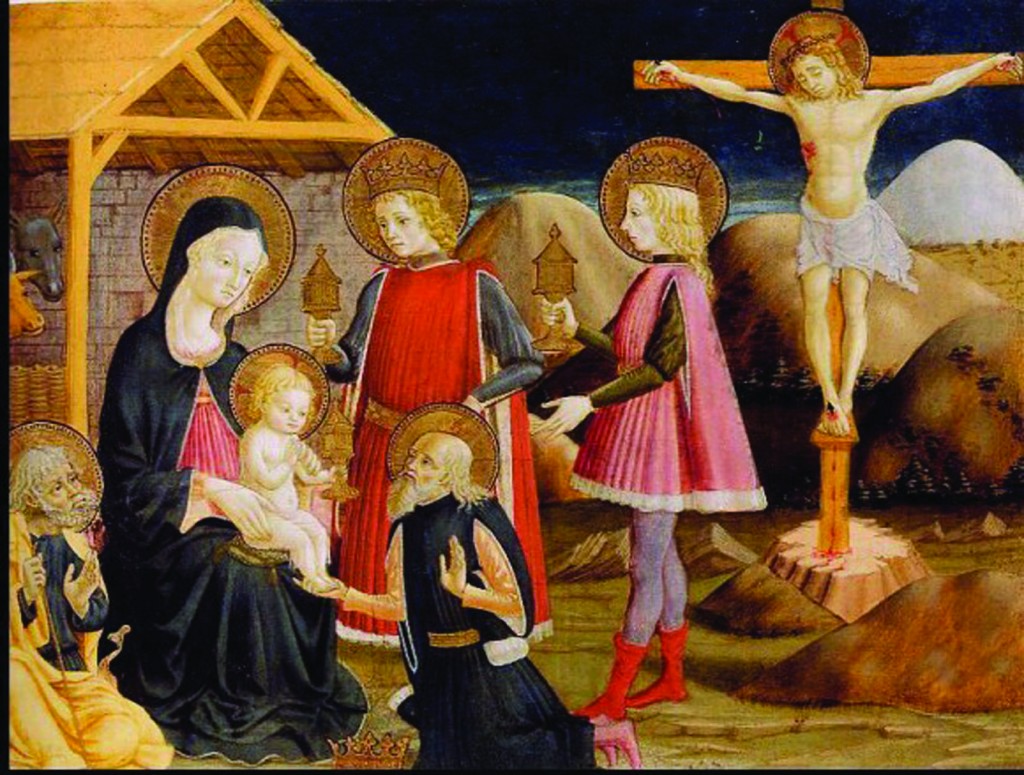

“Adoration of the Magi” and “Christ on the Cross,” by Benedetto Bonfili. British National Gallery, London

A thought meditation on the meaning of the events we celebrate at Christmas, events which respond to the deepest desire of all men and women

Once upon a time there lived this very tall Texan who travelled to Rome to see the sights, his size eclipsing all the buildings in town. Except the Basilica of Saint Peter. At the heart of the Eternal City stood this looming structure that even he couldn’t encompass.

So there he stood, slack-jawed beneath this massive and majestic pile of stone. And looking the expert guide square in the eye, he had but one question: “How much does it weigh?”

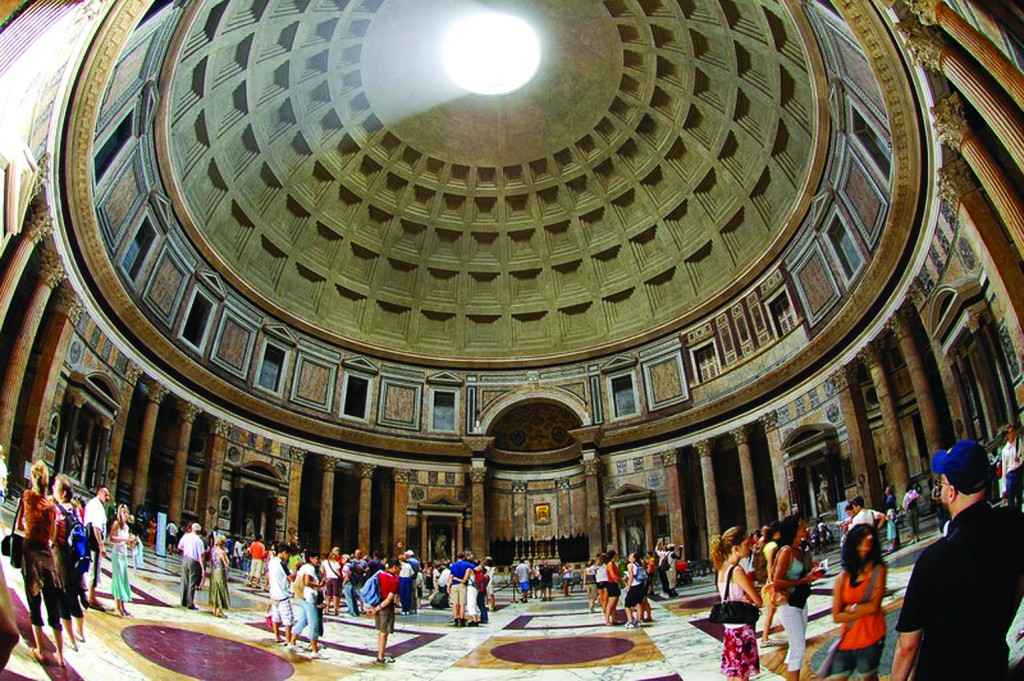

How I love that story. I imagine that tall Texan wandering dopey-eyed from one monument to the next, witlessly intent on learning all sorts of endearingly absurd things. The Coliseum, for instance, about which he would surely want to know, “Why hadn’t someone finished it?” Or the Pantheon, whose opening in the ceiling would instantly prompt him to ask, “What’s the point of a dome unless you’re planning to close it?”

What a charming exhibit of reductionism he represents. Which is the mindset of those for whom the merit of anything is best understood by the ton.

Others might take a dimmer view of the mindless man from Texas. C.S. Lewis, for example, would have filleted the fellow in lard. Indeed, in one of his books, he seriously skewers a chap who, surveying the vastness of the Atlantic Ocean, converts it all into raw material for cornering the salt market. Reductionism, as someone once said, is the sin of calling the pearl the oyster’s mistake.

Take that gaping hole along the roof of the Pantheon, all 27 feet of it. Was it left open by accident? Of course not. Its very emptiness points to the proverbial pearl beyond price. Its existence is a testimony to transcendence, by means of which the pagan spirit was free to take flight. To leap and cavort imaginatively among the stars, above which (who knows?) he might locate those very places where the numinous dwells amid the silence and splendor of the heavens.

The Pantheon was the first pagan building to be baptized by a newly Christianized Rome, a temple once dedicated to all the gods of antiquity, whose light would stream through its opening hundreds of feet above the floor to illumine the soul of man. It thus served as a symbol of the uniquely human struggle to surmount the darkness of death, to breach the finitudes of time and space, and thus commune with the gods. Like a lance pointed at the infinite itself, it evinces that most basic and necessary need of all, which is to lay hold of the Mystery and so free the soul in bondage to the tyranny of time and history.

Ask any pilgrim and he will tell you that here is the deepest desire of all. And like a mark seared upon the soul, it can never be effaced. Nothing can undo the hidden imprint of our belonging to Another. Even if one were to take oneself to hell, there to howl in an anguish of absence forever, one would still bear the image of the One who intended me from all eternity for himself alone. His possession of me is nothing short of my salvation. How else are we to understand the pain of loss unless God, out of an incomprehensible depth of love, had destined all of us for the happiness of heaven?

Hell, then, is the result of man’s resistance to a truth already inscribed in his being; its refusal amid the precincts of the damned must surely be a source of unimaginable torment. Augustine, in a famous passage from the Confessions, reminds us of this fundamental and inescapable fact. “Our hearts are restless, O Lord, until they rest in Thee.”

Interior of the Pantheon, a building on the site of an earlier building commissioned by Marcus Agrippa during the reign of Augustus (27 BC-14 AD)

The fact that each of us is meant for God, that none of us will find lasting fulfillment apart from God, is not the result of a sudden bolt from the blue. It was not necessary that we be given this special sunburst inasmuch as the natural trajectory of a man’s life already urges him along the highroad leading to God. What else is man but a pilgrim in search of a shrine, of a place where, to paraphrase the poet T. S. Eliot, prayer having once been valid, we may kneel in supplication and worship? Hence the perversity of those who persist in denying this profound invitation to cast ourselves into the arms of God.

Between the desire and its consummation, however, there falls the shadow. We simply do not have the native equipment to succeed in scaling such heights. Like a blind beggar fallen down in a ditch, we may imagine the existence of the hidden staircase but, alas, we cannot without grace grope our way out from the darkness toward the mysterious ladder of light.

It is here, therefore, that the overwhelming miracle of Christianity breaks into the darkness of our world, revealing in human history an Event entirely in excess of any human possibility or expectation. God himself enters the human story in order not merely to share the stage on which you and I live and move, but to sanctify and redeem the whole sordid and complicated mess we have made of the play. I who struggle and strain to reach even the outskirts of the Mystery, am all at once absolutely astonished — ambushed — by the Mystery itself, whose dramatic and unforeseen descent into my brokenness is able not just to staunch the wound at the heart of being, but to rescue the entire world from all the hellishness of which it stands condemned.

In other words, the hole in the ceiling has suddenly become an opening allowing God himself to squeeze through. Isn’t this the place where the most palpable difference between religion and Revelation is to be found? That while it is natural for me to aspire to God, to that condition of ideal intimacy with the One who made me, mere religiosity will never be enough to complete the quest; it may launch the rocket into deep space but, wanting in the jet fuel of divine grace, it can never effect a rendezvous with God on the other side.

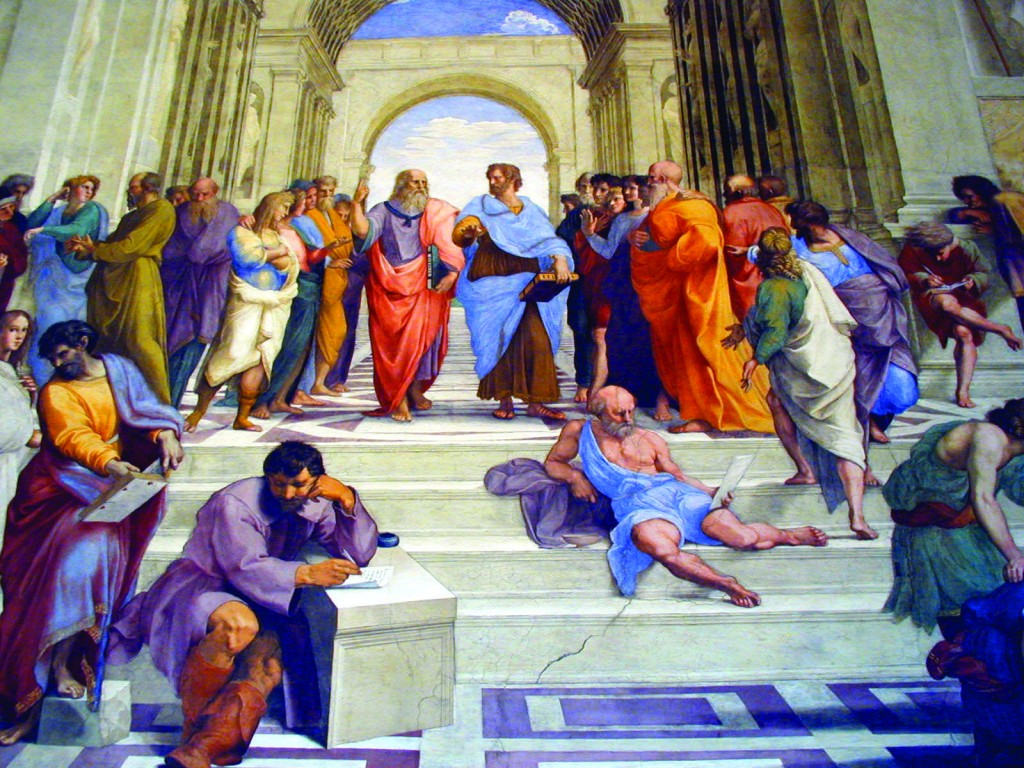

Still, the human spirit thrusting itself toward the unknown God is what makes us human, and who among us would wish to resist so natural a gravitational pull? In the splendid depiction of The School of Athens by the artist Raphael (whose remains, by the way, are in the Pantheon), we see the figure of Plato pointing his finger majestically to heaven. There is the place we long to be, our true and lasting home. Yet in the absence of God’s answering response to the heartfelt cry of eros, revealing a divine largesse poured out upon the world, there can be no hope whatsoever that our own poor hearts, lifted up by sheer force of will, could possibly succeed in their conquest of eternal and divine life. Even Plato could see that in order to cross so great and absolute a sea of being, one would need to call upon the gods themselves to build the bridge. But there are no gods, and so the bridge will never be built.

“The School of Athens” fresco, which is one of Raphael’s most famous works, was completed to decorate the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican

Only the one and true God can save us now, the God and Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ, who not only built the bridge across so infinite a span of sea, but sent his Son in the form of a Child to be that bridge. Pontifex Maximus, we call him. And so thanks to a singularly daring and entirely unexpected feat of engineering, the climax of which is God’s enfleshment as man—the Miracle of Christmas—-you and I are at last able to reach out and touch the face of God.

The very roof of the world, you might say, has been breached. Not by pagan architecture, but by the very Architect himself, to whom we turn before every Holy Communion to ask: Lord, I am not worthy that You should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed.

Dr. Regis Martin, professor of dogmatic and systematic theology at Franciscan University of Steubenville, Ohio, since 1988, is a Faculty Associate with the University’s Veritas Center for Ethics in Public Life.

Facebook Comments