By ITV staff

Interpreting Pope Francis’ Newest Encyclical on “Social Friendship”

Interpreting Pope Francis’ Newest Encyclical on “Social Friendship”

Pope Francis repeatedly makes it clear, in his documents and his talks, his recorded remarks at secular events and interviews with atheist journalists, that he is a Pope for the whole world. “Jesus did not come to earth just for Catholics,” he seems to say, “and I must attend to all God’s children” — though of course we also know him as our “Papa” in a unique way.

So it should not, perhaps, surprise us that he has once again chosen to “break the mold,” depart a bit, as Francis often does, from tradition. How? By writing an encyclical addressed not primarily to the Faithful, or to the Church, or even to Christians, but, clearly and explicitly, to the entire world, believers and nonbelievers alike.

Francis here takes, once again, inspiration from St. Francis of Assisi, who, he says, “transcended differences of origin, nationality, color or religion.”

“St. Francis,” the Pope says of his namesake, “did not wage a war of words aimed at imposing doctrines; he simply spread the love of God.”

And this is what Francis seeks to do in his 43,000-word encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, issued October 3.

In it, the Pope attempts to take stock of the state of brotherly love in the world, to analyze some of the causes of its obvious failures, and to prescribe a way of fraternity, as exemplified by St. Francis — and by the parable of the Good Samaritan.

“So this encounter of mercy between a Samaritan and a Jew [in Christ’s Parable of the Good Samaritan],” Pope Francis says, “is highly provocative; it leaves no room for ideological manipulation and challenges us to expand our frontiers. It gives a universal dimension to our call to love, one that transcends all prejudices, all historical and cultural barriers, all petty interests.”

It is this “universal dimension” that the Pope focuses on, and thus he is led to consider a variety of topics, like economics and government, culture and religion, conflict and peace, that are “universal” to all men in the world.

It is not a document that teaches or reinforces Christian doctrine, in the strict sense, nor is it mainly a spiritual exhortation; indeed, it barely mentions God or Christ.

It is, instead, a kind of “call” to the world of men, a practical call, to love. Still, its implications as a document coming from the hand of the Vicar of Christ, have seemed problematic to some readers (see the texts below).

The document has provoked a variety of reactions, both “pro” or “con,” following mostly “liberal/conservative” identity lines; but not all the reactions have been predictable. Here we present a sampling of excerpts of some of the more thoughtful and incisive commentary, in an attempt to understand the encyclical and its value — as the Holy Father intends — as a gift to the world, in which we are “fratelli tutti” — “all brothers.” Fratelli Tutti is available in its entirety on the Vatican’s website at:

Michael Pakulak on The Catholic Thing website

Michael Pakulak on The Catholic Thing website

As a Professor of Ethics and Social Philosophy in a Catholic university, I find fascinating the encyclical’s use of the language throughout of “social friendship” (amistad social, in Spanish), rather than the familiar “social justice.” There is not a single mention of “social friendship” in the Catechism that I could find, or the Compendium of Catholic Social Doctrine. Here if anywhere in the encyclical is the significant development of the tradition of social thought.

Justice is insufficient for social unity, because of its emphasis on impartiality, which becomes “autonomy” and “individuality” in our culture, also, because of the attention it gives to past wrongs, and the encouragement it gives to anger.

Talk of “social justice,” too, does not adequately ask us to consider the cultures and institutions that are subsidiary to political society, as talk of social friendship does. Pope Francis already points in that direction in the encyclical, with its concern for the “local” and its incisive critique of abuses of social media.

Moreover, mere “social justice” leaves unanswered the question of motivation: how apart from anger, feelings of crisis, and peer pressure (political correctness) are people motivated to effect “social justice”?

So on all these counts, social justice is insufficient.

But if man looks for love and friendship, must he not find Christ?

Fr. Raymond J. de Souza in the National Catholic Register

Fr. Raymond J. de Souza in the National Catholic Register

Indeed, a distinctive character of Fratelli Tutti, not unlike Laudato Si’ before it, is that it is more a political encyclical than a social encyclical. The social vision of Leo XIII was very much that man’s common life comprises many different social realities — marriage, family and Church, for example, coming prior to the state.

This “sociability” of society was the theological basis for the Church’s bold anti-totalitarian teaching, more fully developed by Pope Pius XI in the 1930s. John Paul would later call this the “subjectivity of society,” meaning that society was made up not only of individuals but many social groups that were subjects capable of action in their own right; the state’s role was to assist these groups to flourish, not to supplant them.

In Fratelli Tutti, that rich “sociability” of society takes a backseat to state action. Certainly the Holy Father calls Christians to live out their discipleship in personal encounters with others, especially the afflicted and vulnerable, but for the most part social action is construed as state action. Hence the emphasis in Fratelli Tutti on “political love” — given the prominence of politics in the Pope’s social vision, it is important that politics be imbued with charity.

Bernardo Cervellera on Asianews.it

Bernardo Cervellera on Asianews.it

What the pontiff asks is not a sentimental and generous impulse, but a true conversion to “truth” (a word that goes hand in hand with “charity,” par. 184). This request is made not so much — or not only — to members of religions who, having a common divine origin, are more open to “fraternity,” but also to the world of money and finance, which lives off the dictatorship of an unethical market (par.109); of politics, which drowns in “declarationist nominalism” (par. 187); of the “strong countries” that bleed the cultures of poor countries (par. 51). In the text there is the condemnation of “populism,” so fashionable today (par. 155-ff); but also the condemnation of “relativism,” so loved by the “politically correct” (par. 206-ff).

Francis urgently expresses this request because “the piecemeal third world war” of which he has often spoken, is spreading ceaselessly and enveloping more countries.

“In our world,” he says, “now there are not only ‘pieces’ of war in one country or another, but we are experiencing a ‘piecemeal World War,’ because the fates of countries are strongly connected to each other in the world scenario” (n. 259).

Another element that pushes us to urgency is that ideologies, and those who manage them, have abandoned “all modesty,” unleashing oppression, invasion, kidnapping, human rights violations in an unprecedented fashion: “Things that until a few years ago could not be said by anyone without risking the loss of universal respect can now be said with impunity, and in the crudest of terms, even by some political figures”(par. 45).

Pope Francis’ “dream” leads to the suggestion that human rights are truly universal (par. 206-ff), and that every man can live in a world without borders (par. 124). There is also a request for a reform of the UN, in which even the poorest nations count on an equal footing with the others (par. 173); a forgiveness of the foreign debt of the poorest countries (par. 126); the end of the arms trade, especially in nuclear weapons (par. 262).

All this is based on the commitment of the international community, but is prepared and amplified by personal and group commitment to a culture of dialogue and peace, which is crafted above all by peoples, the Pope writes (par. 217).

The Editorial Staff at the National Catholic Reporter

The Editorial Staff at the National Catholic Reporter

Much of the coverage of Pope Francis’ expansive encyclical Fratelli Tutti, released October 4, focused on its feel-good themes of unity, dialogue and peace. Who can argue against the notion that we are “brothers and sisters all?”

But this document, the Pope’s third encyclical and clearly a summary of his papacy so far, is no rote call for prayers and best wishes in the face of the pandemic. It is, foundationally, a pointed critique of nationalistic populism, of economic systems that exploit the poor, and indeed, of democracy itself, at least as it seems to be evolving at the beginning of the 21st century.

We agree, and appreciate the pontiff’s bold condemnations of neofascist ideas about nation and race, trickle-down economics, unbridled free-market capitalism, income and wealth inequality, and a libertarianism that merely dresses up selfishness for more palatable consumption.

These — along with an excessive individualism and “feverish consumerism” — prevent a “better kind of politics, one truly at the service of the common good,” the Pope says.

There can be no mistaking the Pope’s words: The neoliberal establishment is not compatible with the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

“The marketplace, by itself, cannot resolve every problem, however much we are asked to believe this dogma of neoliberal faith,” Pope Francis writes. “Whatever the challenge, this impoverished and repetitive school of thought always offers the same recipes.”

Italian Vaticanist Sandro Magister

Italian Vaticanist Sandro Magister

In his “Settimo Cielo” (“Seventh Heaven”) column on L’Espresso’s website.

A few days after its publication, the encyclical Fratelli tutti has already been shelved, given the absence in it of the slightest hint of innovation in comparison with the previous and well-known addresses of Pope Francis on the same issues.

But what if precisely this rambling Franciscan homily on “fraternity” were to give birth to a “different Christianity,” in which “Jesus were nothing but a man?” [Note: That is, a “humanistic” Christianity, in which the transcendent (divine) element is removed.]

This is the very serious “dilemma” in which the philosopher Salvatore Natoli sees the Church plunged today, with the pontificate of Jorge Mario Bergoglio.

Natoli writes and argues this in a book by a variety of commentators on Fratelli tutti, edited by the bishop and theologian Bruno Forte, released today in Rome and Italy.

The scholars commenting on the encyclical are of the first order in their respective fields: biblical scholar Piero Stefani, Hebraist Massimo Giuliani, Islamologist Massimo Campanini, historian of Christianity Roberto Rusconi, medievalist Chiara Frugoni, historian of education Fulvio De Giorgi, epistemologist Mauro Ceruti, pedagogist Pier Cesare Rivoltella, poet and writer Arnoldo Mosca Mondadori.

Natoli is one of the leading Italian philosophers. He says he is a nonbeliever, but his training and interests have always focused his attention on the border between faith and reason, bent on the Catholic Church.

In December of 2009, the committee for the “cultural project” of the Italian Church, headed by Cardinal Camillo Ruini, organized in Rome an impressive international conference on the crucial theme: “God today: With Him or without Him changes everything,” Natoli was one of the three philosophers invited to speak, together with the German Robert Spaemann and the Englishman Roger Scruton.

That conference was not a muster of juxtaposed opinions, but aimed straight at what for then-Pope Benedict XVI was the “overriding priority” more than ever before, at a time “when in vast areas of the world the faith is in danger of dying out like a flame which no longer has fuel.” That is, the priority, as the Pope had written that same year in his March 10 letter to the bishops, “of making God present in this world and giving men access to God. Not to any sort of god, but to that God who spoke on Sinai, to that God whose face we recognize in love driven to the very end, in Jesus crucified and risen.”

There is no trace of this dramatic urgency in the 130 pages of Fratelli tutti. But let’s leave the judgment to the philosopher Natoli, in the following moving excerpt from his commentary on the encyclical.

“What if Francis were the last Pope of the Roman Catholic tradition, and a different Christianity were being born?” This question, from philosopher Salvatore Natoli, coincides with the one that historian Roberto Pertici set as the title of his important contribution on Settimo Cielo: “The End of Roman Catholicism?”

The philosopher and the historian, from their respective corners of observation, have grasped in the pontificate of Francis the beginning of the same momentous pivot. This is a convergence of views not to be underestimated.

Salvatore Natoli: “What if Jesus were nothing but a man?”

Salvatore Natoli: “What if Jesus were nothing but a man?”

Modernity has strenuously debated the existence of God; just think of the evaluation of the proofs of God’s existence from Descartes to Kant: can His existence be demonstrated, can it not be demonstrated? Well, the conflict over the existence of God clearly demonstrated that God was the central question of that culture, both for the deniers and for those who upheld Him. It was the dominant theme, one could not be silent about it.

But at a certain point God vanished, He no longer constituted a problem because He was no longer seen as necessary.

Today, reasoning about the existence of God is a problem nobody has, not even Christians.

What characterizes Christianity more and more is the dimension of “caritas,” and less and less that of Transcendence. Fratelli tutti, it appears to me, demonstrates this at every turn. And this is a great dilemma within Christianity, which Pope Francis presents “in actu exercito” (“in real practice”). Transcendence is not denied, but is increasingly ignored. There is no need for explicit denial if the matter becomes irrelevant. “Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum” (“And I look for the resurrection of the dead”) is a statement from the Roman Missal ever more marginal in the Christian vocabulary. “Advancing in the company of men” — an expression that summarizes Fratelli tutti (cf. par. 113) — has always been present, but was simply a step toward a much more radical outcome: definitive redemption from suffering and death. One dimension supported the other.

But today we can see a singular shift: Christianity is increasingly and simply turning into “Christus caritas.” Isn’t this the Christ of Fratelli tutti? A Christ who not by chance — see paragraphs 1-2 and 286 — has the face of St. Francis of Assisi, the Christian saint who speaks most to believers of other religions and to nonbelievers. Is this move — I ask Christians — reversible or irreversible? What if Francis — I dare to conjecture — were the last Pope of the Roman Catholic tradition, and a different Christianity were being born? A Christianity that has justice and mercy at its center, and less and less the resurrection of the flesh?

Fellowship in suffering is not the same thing as ultimate deliverance from evil. The Christian promise was: “there will be no more pain or death, there will be no more evil”; while now Christianity seems to assume that suffering will always accompany men and that being Christian means supporting one another. I emphasize this aspect of the encyclical because to me it seems entirely in keeping with the nobler aims of secular modernity, albeit in terms of altruism and solidarity and without any reference to a definitive redemption, otherwise known as “salvation.” […] I do not know how much importance Christians still attach to faith in the advent of a world without pain and death, and moreover — to me this seemed decisive — in a settling of the score by which men will be compensated for all pain suffered. But I say more: how much do they still believe in a blessed eternity, in an eternal present where there will be nothing more to wait for, but the past will be completely redeemed? […]

In any case, those who are Christians care a great deal about “Christus caritas.” “Ubi caritas et amor, ibi Deus est. Congregavit nos in unum Christi amor” (“Where there is charity and love, there is God. The love of Christ gathers us into one,” again from the Roman Missal): this is all to the good for men.

In any case, those who are Christians care a great deal about “Christus caritas.” “Ubi caritas et amor, ibi Deus est. Congregavit nos in unum Christi amor” (“Where there is charity and love, there is God. The love of Christ gathers us into one,” again from the Roman Missal): this is all to the good for men.

What if Christ were by no means God incarnate but instead the incarnation represented the beginning of the death of God? What if Jesus were nothing but a man who nonetheless showed men that only in their mutual self-giving do they have the possibility of becoming “gods,” albeit in the manner of Spinoza: “homo homini Deus” “(“man to man is a kind of God”)? No longer, therefore, “you come down from the stars,” but rather “supporting one another” in order to dwell happily on the earth.

The promise of a definitive liberation from pain and death may be only a myth, but in any case it is not in the power of those whom the Greeks called “mortals.” Mutual aid, on the contrary, is in men’s power and Christianity, recognized and adopted in the form of the good Samaritan, can truly make us fully human. If this is the case, as Benedetto Croce would say we cannot help but call ourselves Christians. This is a dilemma that I as a nonbeliever pose to believers, to Catholics. In fact, as a nonbeliever, I am in perfect agreement, word for word, with what the encyclical says in the second chapter, commenting on the parable of the good Samaritan.

This is what we need to be doing! From this point of view, Jesus expresses something men are able to do. But rising from the dead is something only God can do, supposing there is one.

Roberto Pertici: Bergoglio’s Reform Was Written Before… by Martin Luther

Roberto Pertici: Bergoglio’s Reform Was Written Before… by Martin Luther

The end of “Roman Catholicism?”

1. At this point in the pontificate of Francis, I believe it can be reasonably maintained that this marks the twilight of that imposing historical reality which can be defined as “Roman Catholicism.”

This does not mean, properly understood, that the Catholic Church is coming to an end, but that what is fading is the way in which it has historically structured and represented itself in recent centuries.

It seems evident to me, in fact, that this is the plan being deliberately pursued by the “brain trust” that has clustered around Francis: a plan understood both as an extreme response to the crisis in relations between the Church and the modern world, and as a precondition for a renewed ecumenical course together with the other Christian confessions, especially the Protestant.

2. By “Roman Catholicism” I mean that grand historical, theological, and juridical construction which has its origin in the Hellenization (in terms of the “philosophical aspect”) and Romanization (in terms of the political-juridical aspect) of primitive Christianity, and is based on the primacy of the successors of Peter, as emerges from the crisis of the late ancient world and from the theoretical systematization of the Gregorian age (“Dictatus Papae”).

2. By “Roman Catholicism” I mean that grand historical, theological, and juridical construction which has its origin in the Hellenization (in terms of the “philosophical aspect”) and Romanization (in terms of the political-juridical aspect) of primitive Christianity, and is based on the primacy of the successors of Peter, as emerges from the crisis of the late ancient world and from the theoretical systematization of the Gregorian age (“Dictatus Papae”).

Over the subsequent centuries, the Church also established its own internal legal system, canon law, looking to Roman law as its model. And this juridical element contributed to gradually shaping a complex hierarchical organization with precise internal norms that regulate the life both of the “bureaucracy of celibates” (an expression of Carl Schmitt, 1888-1985) that manages it and of the laity who are part of it.

The other decisive moment of formation of “Roman Catholicism” is, finally, the ecclesiology elaborated by the Council of Trent, which reiterates the centrality of ecclesiastical mediation in view of salvation — in contrast with the Lutheran theses of the “universal priesthood” — and therefore established the hierarchical, united, and centralized character of the Church; its right to supervise and, if need be, to condemn positions that are in contrast with the orthodox formulation of the truths of faith; its role in the administration of the sacraments. This ecclesiology finds its seal in the dogma of pontifical infallibility proclaimed by Vatican Council I, put to the test 80 years later in the dogmatic affirmation of the Assumption of Mary into heaven (1950), which together with the previous dogmatic proclamation of her Immaculate Conception (1854) also reiterates the centrality of Marian devotion. It would be reductive, however, if we were to limit ourselves to what has been said so far. Because there also exists — or better, existed — a widespread “Catholic mindset,” made up of the following:

• a cultural attitude based on a sometimes disenchanted [Note: pragmatic] realism about human nature that is willing to “understand all” as a precondition for “forgiving all”;

• a non-ascetic spirituality that is understanding toward certain material aspects of life, and not inclined to disdain them;

• engagement in everyday charity toward the humble and needy, without the need to idealize them or almost make new idols of them;

• a willingness also to represent itself in its own magnificence, and therefore not deaf to the evidence of beauty and of the arts, as testimony to a supreme Beauty toward which the Christian must tend;

• a subtle examination of the most inward movements of the heart, of the interior struggle between good and evil, of the dialectic between “temptations” and the response of conscience.

It could therefore be said that in what I call “Roman Catholicism” there are interwoven three aspects, obviously in addition to that of religion: the aesthetical, the juridical, the political. This is a matter of a rational vision of the world that makes of itself a visible and solid institution and fatally enters into conflict with the idea of representation that emerged in modernity, based on individualism and on a conception of power that, rising from the bottom up, ends up bringing into question the principle of authority.

3. This conflict has been considered in different ways, often opposing, by those who have analyzed it. Carl Schmitt looked with admiration to the “resistance” of “Roman Catholicism,” considered the last force capable of reining in the dissipatory forces of modernity. Others have made tough criticisms of him: in this struggle, the Catholic Church is seen as having ruinously emphasized its juridical-hierarchical, authoritarian, external traits.

Beyond these opposing evaluations, it is certain that in recent centuries “Roman Catholicism” has been pushed onto the defensive. What has gradually brought its social presence into question has been above all the birth of industrial society and the consequent process of modernization, which has opened a series of anthropological mutations that are still underway. Almost as if “Roman Catholicism” were “organic” (to say it the old Marxist way) to a society that is agrarian, hierarchical, static, based on penury and fear, and instead could not find relevance in a society that is “affluent,” dynamic, characterized by social mobility.

A first response to this situation of crisis was given by the ecumenical council Vatican II (1962-1965), which, according to the intentions of Pope John XXIII (1958-1963), who had convened it, was to effect a “pastoral updating,” looking with new optimism at the modern world, which meant finally letting the guard down: no longer carrying on with an age-old duel, but opening a dialogue and effecting an encounter.

The world was swept up during those years in extraordinary changes and in an unprecedented economic development: probably the most sensational, rapid, and profound revolution in the human condition of which there is any trace in history (Eric J. Hobsbawm). The event of the Council contributed to this mutation, but was in its turn engulfed by it: the rhythm of the “updatings” — fostered also by the dizzying transformations in the surroundings and by the general conviction, sung by Bob Dylan, that “the times they are a-changin’” — got out of hand for the hierarchy, or at least for that part of it which wanted to effect a reform, not a revolution.

Thus between 1967 and 1968 one witnessed the “watershed” of Paul VI, which expressed itself in the preoccupied analysis of the turbulence of ’68 and then of the “sexual revolution” contained in the encyclical Humanae Vitae of July 1968. So great was the pessimism to which that great pontiff came in the 1970s that, conversing with the philosopher Jean Guitton, he wondered to himself and asked him, echoing a disquieting passage from the Gospel of Luke: “When the Son of Man returns, will he still find faith upon the earth?”

And Paul added: “What strikes me, when I consider the Catholic world, is that within Catholicism there sometimes seems to predominate a type of thinking that is not Catholic, and it could happen that this non-Catholic thinking within Catholicism could tomorrow become the stronger [Note: i.e., predominant] one.”

***

4. It is well known how the successors of Paul VI responded to this situation: by combining change and continuity; effecting — on certain questions — the appropriate corrections (memorable, from this point of view, was the condemnation of “liberation theology”); and by seeking a dialogue with modernity that would be at the same time a challenge on the issues of life, the rationality of man, religious freedom.

Paul VI at Vatican II.

Benedict XVI, in what was the true agenda-setting text of his pontificate (the address to the pontifical curia of December 22, 2005), then reiterated a firm point: that the great decisions of Vatican II were to be read and interpreted in the light of the preceding tradition of the Church, and therefore also of the ecclesiology that emerged from the Council of Trent and from Vatican II. Even for the simple reason that one cannot effect a formal recantation of the faith believed and lived by generations and generations, without introducing an irreparable “vulnus” (“wound”) in the self-representation and widespread perception of an institution like the Catholic Church.

Paul’s friend, French philosopher Jean Guitton, defender of the encyclical Humanae Vitae (1968)

It is also known how this stance caused a widespread rejection not only “extra ecclesiam” (“outside of the Church”) where it manifested itself in an aggression against Benedict XVI in the media and in intellectual circles that was absolutely unprecedented, but — in the manner of Nicodemus and the murmuring that are congenital in the clerical world — also in the ecclesiastical body, which essentially left that Pope alone in the most critical moments of his pontificate. This led, I believe, to his resignation in February of 2013, which — apart from the reassuring interpretations — appears as an epochal event, the reasons and long-term implications of which still remain entirely to be explored.

5. This was the situation inherited by Pope Francis. I limit myself only to pointing out the biographical and cultural aspects that in part made Jorge Mario Bergoglio “ab initio” (“from the beginning”) an outsider to what I have called “Roman Catholicism”:

• the peripheral character of his formation, profoundly rooted in the Latin American world, which makes it difficult for him to embody the universality of the Church, or at least drives him to live it in a new way, pushing to the side European and North American civilization;

• his membership in an order, like the Society of Jesus, that over the past half century has effected one of the most sensational political-cultural repositionings ever heard of, moving from a “reactionary” position to one that is variously “revolutionary” and thus giving proof of a pragmatism that in many of its aspects is worthy of reflection;

• his estrangement from the aesthetic dimension that is proper to “Roman Catholicism,” his showy renunciation of any representation of dignity of office (the pontifical apartments, the red mozzetta and the usual pontifical trappings, like the papal summer palace in Castel Gandolfo) and what he calls “customs of a Renaissance prince” (starting with being late for and then absent from a concert of classical music in his honor at the beginning of the pontificate).

I would rather seek to emphasize what could be in my opinion the unifying element of the many mutations that Pope Francis is introducing in Catholic tradition. I do so basing myself on a little book by an eminent Churchman, who is generally considered the theologian of reference for the current pontificate, eloquently cited by Francis as early as his first Angelus, on March 17, 2013, when he said: “In the past few days I have been reading a book by a Cardinal — Cardinal (Walter) Kasper, a clever theologian, a good theologian — on mercy. And that book did me a lot of good, but do not think I am promoting my cardinals’ books! Not at all! Yet it has done me so much good, so much good.”

The book by Walter Kasper to which I am referring is entitled: Martin Luther: An Ecumenical Perspective, and it is the reworked and expanded version of a talk Kasper gave on January 18, 2016, in Berlin. The chapter to which I would like to call attention is the sixth: “The ecumenical relevance of Martin Luther.”

The whole chapter is built on a binary argumentation, according to which Luther was led to deepen the rupture with Rome primarily because of the refusal of the Popes and the bishops to proceed with a reform. It was only in the face of Rome’s deafness, Kasper writes, that the German reformer, “on the basis of his understanding of the universal priesthood, had to content himself with an emergency organization. He continued, however, to trust in the fact that the truth of the Gospel would assert itself on its own, and he therefore left the door fundamentally open for a possible future agreement.”

But also on the Catholic side, at the beginning of the 16th century, many doors remained open, and in short there was a fluid situation. Kasper writes: “There was no harmoniously structured Catholic ecclesiology, but only approaches that were more a doctrine on the hierarchy than a real and proper ecclesiology. The systematic elaboration of ecclesiology would take place only in controversial theology, as an antithesis to the polemics of the Reformation against the papacy. The papacy thus became, in a way unknown until then, the distinguishing mark of Catholicism. The respective confessional theses and antitheses influenced and impeded each other.”

One must therefore proceed today — according to the overall meaning of Kasper’s argumentation — with a “deconfessionalization” of both the Reformed confessions [Note: i.e., Lutheranism] and of the Catholic Church, in spite of the fact that this never portrayed itself as a “confession,” but as the universal Church. One must return to something like the situation that preceded the outbreak of the religious conflicts in the 16th century.

One of the characteristically less “ecclesial” gestures of Pope Francis’ pontificate

German Cardinal Walter Kasper

While in the Lutheran camp this “deconfessionalization” has already been widely achieved (with the aggressive secularization of those societies, for which the problems that were at the foundation of the confessional controversies became irrelevant for the overwhelming majority of “Reformed” Christians), in the Catholic camp, instead, there is still much to be done, precisely because of the survival of aspects and structures of what I have called “Roman Catholicism.” It is therefore above all to the Catholic world that the invitation to “deconfessionalization” is addressed. Kas per invokes this as a “rediscovery of original catholicity, not restricted to a confessional point of view.” To this end, it would therefore be necessary to bring to completion the surmounting of Tridentine ecclesiology and that of Vatican I. According to Kas per, Vatican II opened the way, but its reception has been controversial and anything but straightforward.

This brings us to the role of the current pontiff: “Pope Francis has inaugurated a new phase in this process of reception. He emphasizes the ecclesiology of the People of God, the People of God on the journey, the sense of faith of the People of God, the synodal structure of the Church, and for the comprehension of unity is putting an interesting new approach into play. He no longer describes ecumenical unity with the image of concentric circles around the center, but with the image of the polyhedron, a multifaceted reality, not a ‘puzzle’ put together from the outside, but a whole, and, since this is a matter of a precious stone, a whole that reflects the light that strikes it in a marvelously multiple way. Reconnecting with Oscar Cullmann, Pope Francis borrows the concept of diversity reconciled.”

6. if we briefly reconsider in this light the behaviors of Francis that have raised the biggest sensation, we better understand their unifying logic:

• his emphasis, right from the day of the election, of his office as bishop of Rome, rather than as pontiff of the universal Church;

• his destructuring of the canonical figure of the Roman pontiff (the famous “who am I to judge?”), at the basis of which — therefore — are not only the factors of character mentioned above, but a deeper reason, of a theological nature;

• the practical downgrading of some of the most characteristic sacraments of the “Catholic mindset” (auricular confession, indissoluble marriage, the Eucharist), realized for pastoral reasons of “mercy” and “welcome”;

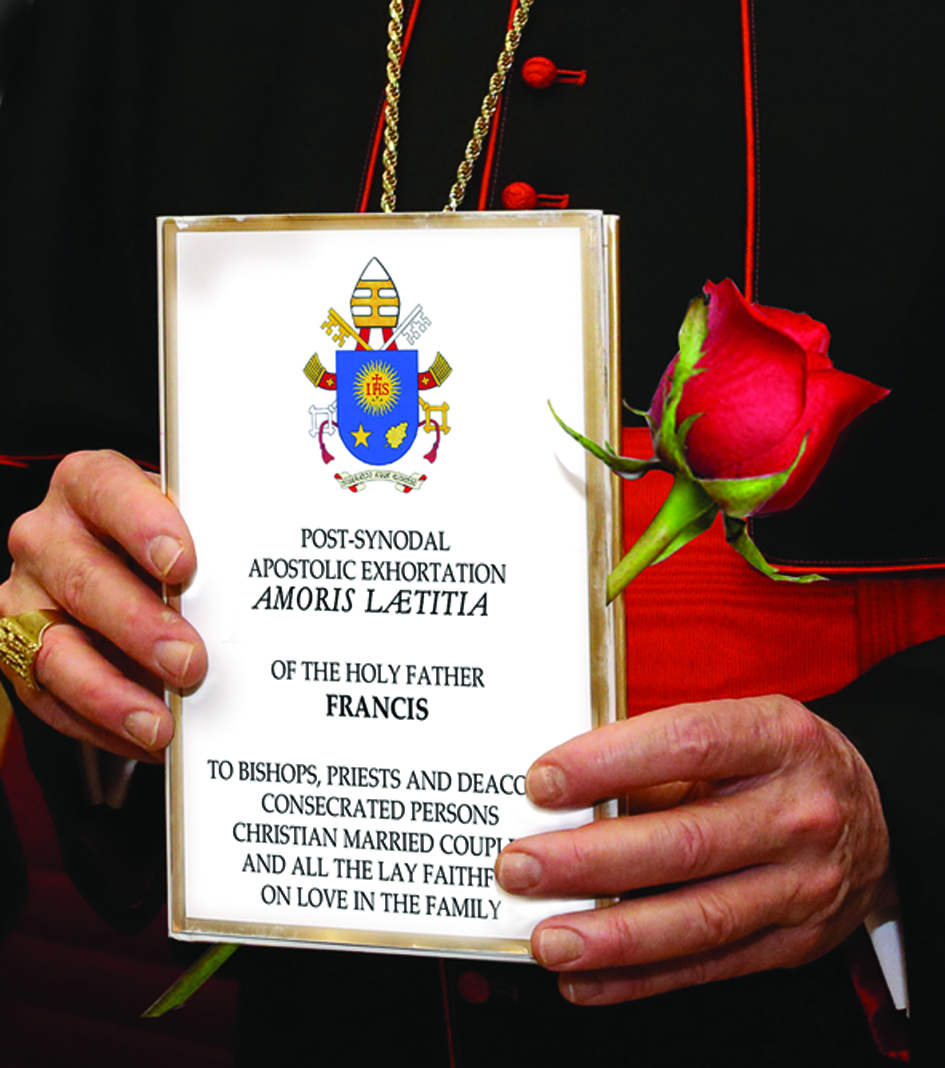

• the exaltation of “parrhesìa” [“bold truth telling”] within the Church, of presumedly creative confusion, to which is added a vision of the Church almost as a federation of local Churches, each endowed with extensive disciplinary, liturgical and even doctrinal powers. There are those who feel scandalized by the fact that in Poland an interpretation of Amoris Laetitia will go into effect that is different from the one that will be realized in Germany or in Argentina, concerning communion for the divorced and remarried. But Francis could respond that this is a matter of different sides of that polyhedron which is the Catholic Church, to which could also be added sooner or later — why not? — the post-Lutheran Reformed Churches, precisely in a spirit of “diversity reconciled.”

On this path, it is easy to foresee that the next steps will be a rethinking of catechesis and of the liturgy in an ecumenical sense, here too with the journey facing the Catholic side being much more demanding than the one facing the “Protestant” side, considering the different points of departure, as also a downgrading of the sacred order in its most “Catholic” aspect, meaning in ecclesiastical celibacy, with the result that the Catholic hierarchy will even cease to be the Schmittian “bureaucracy of celibates.” One understands better, then, the genuine exaltation of the figure and work of Luther that was produced at the top of the Catholic Church on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of 1517 [i.e., in 2017] all the way to the controversial stamp dedicated to him by the Vatican post office, with Luther and his associate, Melanchthon, at the feet of Jesus on the cross.

Personally I have no doubt that Luther is one of the giants of “universal history,” as it used to be commonly called, but “est modus in rebus” [Note: Latin for “there is a proper measure in things”]: above all the institutions must have a sort of modesty in carrying out upheavals in these dimensions, on pain of ridicule: the same sort with which we were assailed in the 20th century, when we saw the communists back then rehabilitating in unison and by command the “heretics” that they had strenuously condemned and fought until the day before: the “Counterorder, comrades!” of the cartoons by Giovannino Guareschi [Note: i.e., Europe’s communists some decades ago attempted to reconcile various “heretical” communist factions, leading some to ridicule them for saying, “You are out! No, now you are back in!”; so the Church, if she wishes to “reconcile” “heretical groups” must act “modestly,” or risk ridicule.]

7. So if yesterday “Roman Catholicism” was perceived as a foreign body by modernity, a foreignness for which it was not pardoned, it is natural that its twilight should now be hailed with joy by the “modern world” in its political, media, and cultural institutions, and that therefore the current pontiff should be seen as the one who is healing that fracture between the ecclesiastical hierarchy and the world of information, of international organizations and “think tanks,” which — opened in 1968 with Humanae Vitae — had become deeper during the subsequent pontificates.

7. So if yesterday “Roman Catholicism” was perceived as a foreign body by modernity, a foreignness for which it was not pardoned, it is natural that its twilight should now be hailed with joy by the “modern world” in its political, media, and cultural institutions, and that therefore the current pontiff should be seen as the one who is healing that fracture between the ecclesiastical hierarchy and the world of information, of international organizations and “think tanks,” which — opened in 1968 with Humanae Vitae — had become deeper during the subsequent pontificates.

And it is also natural that ecclesiastical groups and circles that already in the 1970s were hoping for the surpassing of the Tridentine Church and interpreted Vatican II in this perspective, after having lived under wraps over the prior 40 years, have today come out into the open and with their lay and ecclesiastical heirs should figure among the components of that “brain trust” which was mentioned at the beginning. [Note: i.e., the “progressives” have come forward to fill the “brain trust” circle around Pope Francis — a phenomenon he suggests is “natural.”]

There remain open, however, several questions that would impose further reflections that are not easy. Will the operation carried forward by Pope Francis and by his “entourage” see lasting success, or will it end up encountering resistance within the hierarchy and what remains of the Catholic people, greater than the decidedly marginal forms that have emerged so far? More in general: what consequences could this have on the overall cultural, political, religious cohesion of the Western world, which, in spite of having reached an elevated level of secularization, has long had one of its load-bearing structures precisely in “Roman Catholicism”? But it is preferable that historians would not make prophecies and would content themselves with understanding something, if they are able, about the processes underway. (Translation by Matthew Sherry, Ballwin, Missouri, U.S.A.)

Facebook Comments