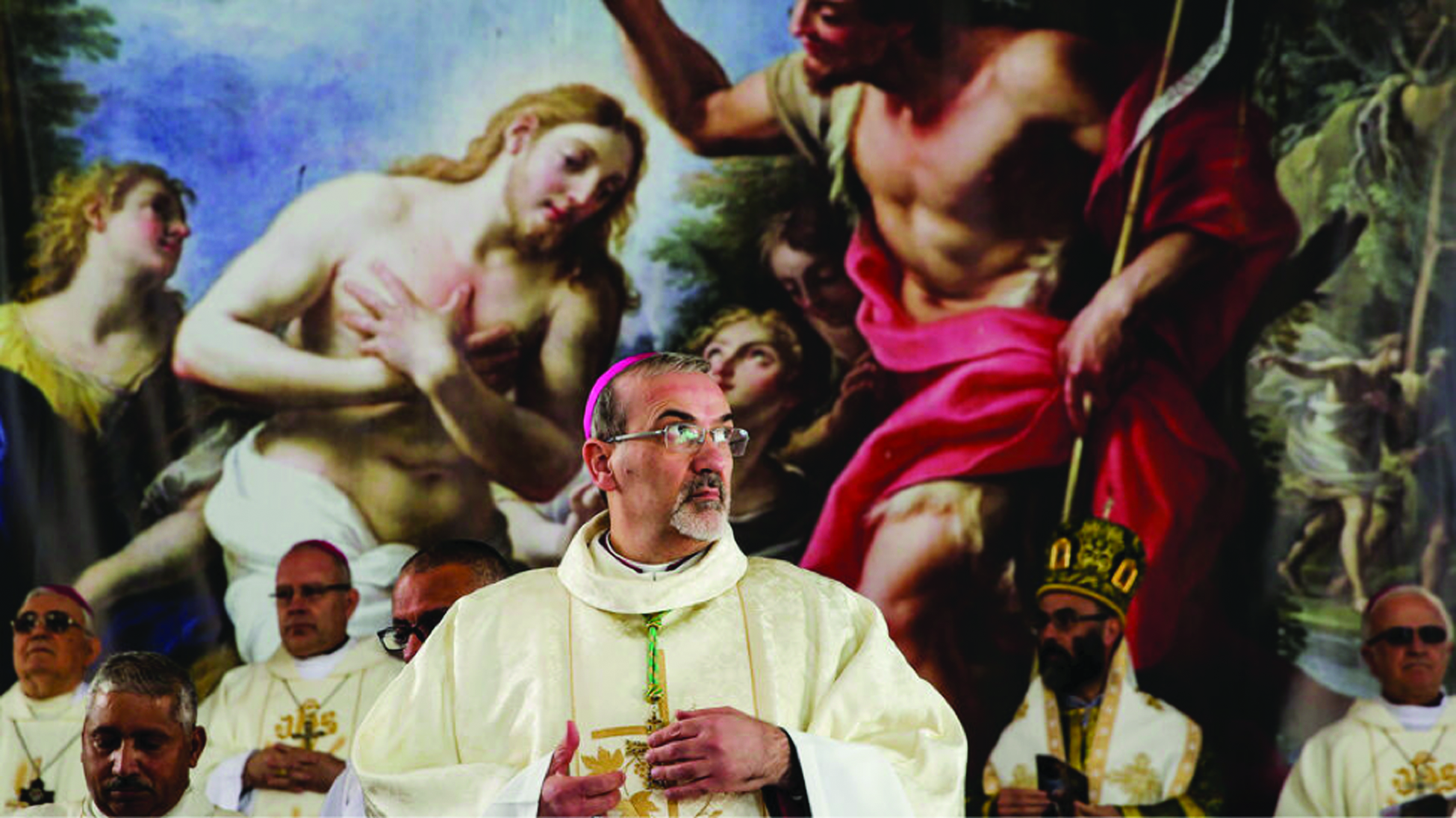

Archbishop Dominique Mamberti speaks to the United Nations in New York.

Two years ago, Cardinal-designate Dominique Mamberti on January 16, 2013, granted an important interview to Vatican Radio which is published on the Vatican’s website. The interview is a thoughtful discussion of freedom for the Church and for Christian belief in an increasingly secular society, in light of cases then before the European Court of Human Rights. Can a Christian wear a cross at work? Can a Christian object in conscience to the celebration of civil unions between members of the same sex, or will this be made illegal? Mamberti’s remarks reveal his mind, and are worth reading…

Your Excellency, on January 15, 2013, the European Court of Human Rights published its judgments on four cases relating to freedom of conscience and religion of employees in the United Kingdom. Two of these cases concern employees’ freedom to wear a small cross around their neck in the workplace, while the other two concern the freedom to object in conscience to the celebration of a civil union between persons of the same sex and to conjugal counseling for couples of the same sex. Only in one case the Court held in favor of the applicant.

Cardinal-designate Dominique Mamberti: These cases show that questions relating to freedom of conscience and religion are complex, in particular in European society marked by the increase of religious diversity and the corresponding hardening of secularism. There is a real risk that moral relativism, which imposes itself as a new social norm, will come to undermine the foundations of individual freedom of conscience and religion. The Church seeks to defend individual freedoms of conscience and religion in all circumstances, even in the face of the “dictatorship of relativism.” To this end, the rationality of the human conscience in general and of the moral action of Christians in particular requires explanation. Regarding morally controversial subjects, such as abortion or homosexuality, freedom of conscience must be respected. Rather than being an obstacle to the establishment of a tolerant society in its pluralism, respect for freedom of conscience and religion is a condition for it. Addressing the Diplomatic Corps accredited to the Holy See last week, Pope Benedict XVI stressed that “in order to effectively safeguard the exercise of religious liberty it is essential to respect the right of conscientious objection. This ‘frontier’ of liberty touches upon principles of great importance of an ethical and religious character, rooted in the very dignity of the human person. They are, as it were, the ‘bearing walls’ of any society that wishes to be truly free and democratic. Thus, outlawing individual and institutional conscientious objection in the name of liberty and pluralism paradoxically opens by contrast the door to intolerance and forced uniformity.”

The erosion of freedom of conscience also witnesses to a form of pessimism with regard to the capacity of the human conscience to recognize the good and the true, to the advantage of positive law alone, which tends to monopolize the determination of morality. It is also the Church’s role to remind people that every person, no matter what his beliefs, has, by means of his conscience, the natural capacity to distinguish good from evil and that he should act accordingly. Therein lies the source of his true freedom.

Some time ago the Holy See’s Mission to the Council of Europe published a Note on the Church’s freedom and institutional autonomy. Could you explain the context of the Note?

Mamberti: The issue of the Church’s freedom in her relations with civil authorities is at present being examined by the European Court of Human Rights in two cases involving the Orthodox Church of Romania and the Catholic Church. These are the Sindacatul “Pastorul cel Bun” versus Romania and Fernandez Martinez versus Spain cases. On this occasion the Permanent Representation of the Holy See to the Council of Europe drew up a synthetic note explaining the magisterium (official Church teaching) on the freedom and institutional autonomy of the Catholic Church.

What is at stake in these cases?

Mamberti:

In these cases, the European Court must decide whether the civil power respected the European Convention on Human Rights in refusing to recognize a trade union of priests (in the Romanian case) and in refusing to appoint a teacher of religion who publicly professes positions contrary to the teaching of the Church (in the Spanish case). In both cases, the rights to freedom of association and freedom of expression were invoked in order to constrain religious communities to act in a manner contrary to their canonical status and the Magisterium. Thus, these cases call into question the Church’s freedom to function according to her own rules and not to be subject to civil rules other than those necessary to ensure that the common good and just public order are respected. The Church has always had to defend herself in order to preserve her autonomy with regard to the civil power and ideologies. Today, an important issue in Western countries is to determine how the dominant culture, strongly marked by materialist individualism and relativism, can understand and respect the nature of the Church, which is a community founded on faith and reason.

How does the Church understand this situation?

Mamberti: The Church is aware of the difficulty of determining the relations between the civil authorities and the different religious communities in a pluralistic society with regard to the requirements of social cohesion and the common good. In this context, the Holy See draws attention to the necessity of maintaining religious freedom in its collective and social dimension. This dimension corresponds to the essentially social nature both of the person and of the religious fact in general. The Church does not ask that religious communities be lawless zones but that they be recognized as spaces for freedom, by virtue of the right to religious freedom, while respecting just public order. This teaching is not reserved to the Catholic Church; the criteria derived from it are founded in justice and are therefore of general application.

Furthermore, the juridical principle of the institutional autonomy of religious communities is widely recognized by States which respect religious freedom, as well as by international law. The European Court of Human Rights itself has regularly stated this principle in several important judgments. Other institutions have also affirmed this principle. This is notably the case with the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe) and also with the United Nations Committee for Human Rights in, respectively, the Final Document of the Vienna Conference of January 19, 1989, and General Observation No. 22 on the Right to Freedom of Thought, Conscience and Religion of July 30, 1993. It is nevertheless useful to recall and defend this principle of the autonomy of the Church and the civil power.

How is this Note set out?

Mamberti: The Church’s freedom will be better respected if it is, first of all, well understood, without prejudice, by the civil authorities. It is therefore necessary to explain how the Church’s freedom is envisaged. To this end, the Permanent Representation of the Holy See to the Council of Europe drew up a synthetic Note (which is here attached) explaining the Church’s position on the basis of four principles: 1) the distinction between the Church and the political community; 2) freedom in relation to the State; 3) freedom within the Church; 4) respect for just public order. Following the explanation of these principles, the Note also presents the more pertinent extracts from the Declaration on Religious Freedom Dignitatis Humanae and the Pastoral Constitution Gaudium et Spes of the Second Vatican Council.

Facebook Comments