Hymns That Remind Us the Christian Life is a Battle to Be Won

By Anthony Esolen

All Saints’ Day is upon us, and that means that Catholics in English-speaking countries may well be singing the mighty “For All the Saints,” the only hymn most of us have all year long that refers to the Christian life as a battle. The absence is striking. In every hymnal I own that was printed before 1960, but in no Catholic hymnal that I know of since then, you will find around 20 or 30 hymns, out of the typical 600 or so, that are meant to rouse up Christian courage, and naturally most of these are of a markedly masculine character.

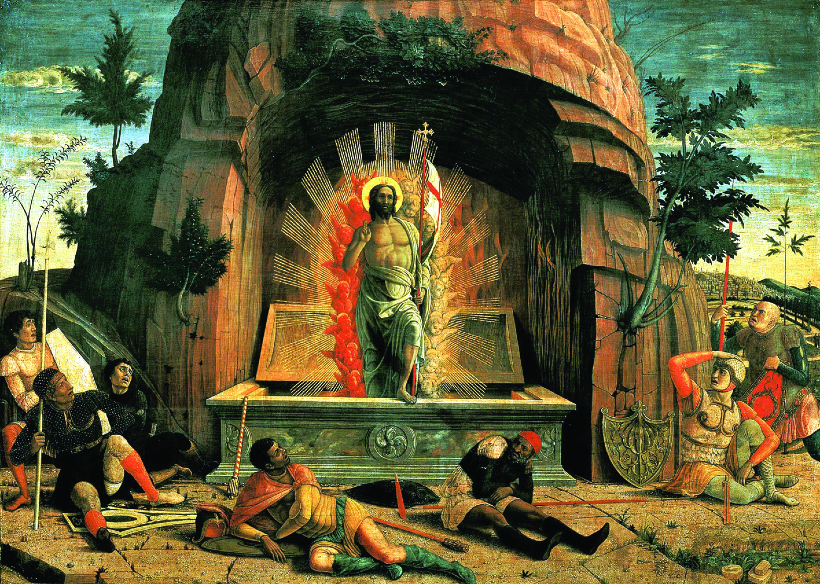

Armed Angels of Guariento di Arpo, Civic Museums, Padua, Italy

My favorite may be Charles Wesley’s “Soldiers of Christ, Arise,” sung to a sprightly march, called “Silver Street”:

Soldiers of Christ, arise,

And put your armor on,

Strong in the strength which God supplies

Through his eternal Son.

So armed, we need not fear, and we can say, with the psalmist, that we go “from strength to strength” (Ps. 84:7), we can “tread down the wicked” (Mal. 4:3), and we can win what Saint Paul won, who “fought the good fight,” and finished the race, and kept the faith, as he wrote to Timothy, the old veteran to the young colonel (2 Tim. 4:7):

From strength to strength go on,

Wrestle, and fight, and pray:

Tread all the powers of darkness down

And win the well-fought day.

For a venerable ancient hymn to encourage the fighting Christian, a hymn with a most unusual structure and text, go to “Christian, Dost Thou See Them.” It is best sung to the melody Saint Andrew of Crete, named for the saint (660-732) to whom the original Greek is attributed. That melody was composed by the hymnodist John B. Dykes specifically for the English translation, and it works brilliantly. In each of the first three stanzas, the opening lines, sung in a minor key, are a question addressed to the Christian, and in fact the first two lines have only one note, eleven times in a row, strange and menacing. But the final lines burst through in a major key, and answer the challenge:

Christian, dost thou see them

On the holy ground,

How the powers of darkness

Rage thy steps around?

Christian, up and smite them,

Counting gain but loss,

In the strength that cometh

By the holy cross.

That surely gives us a rush of encouragement, and we might expect the whole poem to go on in that way. But the final stanza departs from the pattern, and it is like no other I am aware of, in any hymn. It does not begin with a question. It is a straight address to us, from Christ Himself – printed in the hymnals with quotation marks, so that we do not pretend to be singing Christ’s words as if they were ours:

“Well I know thy trouble,

O my servant true;

Thou art very weary,

I was weary too.”

So simple, almost childlike! Imagine, to hear those words from Christ’s lips. Imagine it, in your dark nights, when friends are far away, or they have forgotten you, when all you set your hand to seems to fail, and you hear the snickering of the demons as they tempt you to give up, to be despondent, to lie down on the path and never rise. Imagine, it is Christ speaking, and he does know our trouble, because he bore it on his shoulders, and he knows what it is to be weary, because he climbed that dreadful hill of the Skull, carrying the cross, the weight of all men’s folly and darkness and sin. But he does not cast it in our teeth. All he says here, with infinite understatement, is, “I was weary, too.” And then in the major key comes the promise:

“But that toil shall make thee

Someday all mine own,

And the end of sorrow

Shall be near my throne.”

Why should such hymns feel strange to us? Have we not been forewarned? Warfare is the Christian’s calling – not to slay other people, an obsession for the fanatic and a diversion for the hedonist, but to enter the lists for the truth, for “we are contending not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against the powers, against the spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places” (Eph. 6:12). So we must put on the whole armor of God, says Saint Paul.

The Greek word is panoplia, whence we derive the English word panoply, a bit misleading if we so translate it here, because we now think of panoply as a lot of fancy regalia, all fuss and feathers. But panoplia refers to the full armor of a Greek hoplites, a foot-soldier – in modern Greek, an infantryman. The soldier usually carried a spear in his right hand and a shield in his left, to protect the man to his left as they marched in orderly ranks. If you could afford it, you wore a bronze breastplate, a helmet, and greaves to protect your feet. So when Paul imagines someone wearing the panoply of God, he can enumerate each of the items, and what he says would surely bring many a sharp image and clear memory to those who heard him: “Stand therefore, having fastened the belt of truth around your waist, and having put on the breastplate of righteousness, and having shod your feet with the equipment of the gospel of peace; besides all these, taking the shield of faith, with which you can quench all the flaming darts of the Evil One. And take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God” (Eph. 6:14-17).

Choir of Angels by Paolo Veneziano, National Museum of the Palace of Venice, Italy

What need we fear, then? Our countenances may well be bright. “Be of good cheer,” says Jesus; “I have overcome the world” (Jn. 16:33). The Greek there is nenikeka – I have gotten the nikē, the victory. Well then, why should we not sing a perfectly cheerful song of Christian warfare?

The jauntiest and boldest of all these hymns is, to my ear, “He Who Would Valiant Be,” an intelligent adaptation of one of the little poems from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, this one describing the firm confidence of Mr. Valiant-for-the-Truth. Ralph Vaughn Williams set the poem to an English sailor-song he discovered in a Wessex village (Monks Gate); it’s the same Vaughn Williams who composed the grand melody Sine Nomine for our beloved “For All the Saints,” though most of our editors have mangled that poem’s grammar and emasculated its imagery, leaving it a bloody mess. The editors of the hymnal that Vaughn Williams himself worked on, however, knew what they were doing, poetically, musically, and Scripturally, and here is what they did for Bunyan’s poem. I will end with these words. I can’t improve on them, and they need no commentary. But I do urge you to sing it out:

He who would valiant be

‘Gainst all disaster,

Let him in constancy

Follow the Master.

There’s no discouragement

Shall make him once relent

His first avowed intent,

To be a pilgrim.

Whoso beset him round

With dismal stories,

Do but themselves confound;

His strength the more is.

No foes shall stay his might,

Though he with giants fight;

He will make good his right

To be a pilgrim.

Since, Lord, thou dost defend

Us with thy Spirit,

We know we at the end

Shall life inherit.

Then fancies flee away!

I’ll fear not what men say,

I’ll labor night and day

To be a pilgrim.

Facebook Comments