More than a century ago, Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson foresaw the rise of secular humanism, the contraction of the Catholic Church, and the Coming of the Antichrist…

By ITV Staff

Editor’s Note: The passage below is from the novel Lord of the World, written by the English Catholic convert Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson (the son of the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury) in 1907. He attempts a vision of the world more than a century in the future — in the early 21st century… our own time… predicting the rise of Communism, the fall of faith in many places, the advance of technology (he foresees helicopters) and so forth, up until… the Second Coming of the Lord, with which his vision ends. For this reason, and also because Pope Benedict and Pope Francis have repeatedly cited Benson’s book, saying its clarification of the danger of a type of humanitarianism without God is a true danger that we do face, we are printing selections from it in ITV, now and in the months ahead.

Editor’s Note: The passage below is from the novel Lord of the World, written by the English Catholic convert Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson (the son of the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury) in 1907. He attempts a vision of the world more than a century in the future — in the early 21st century… our own time… predicting the rise of Communism, the fall of faith in many places, the advance of technology (he foresees helicopters) and so forth, up until… the Second Coming of the Lord, with which his vision ends. For this reason, and also because Pope Benedict and Pope Francis have repeatedly cited Benson’s book, saying its clarification of the danger of a type of humanitarianism without God is a true danger that we do face, we are printing selections from it in ITV, now and in the months ahead.

LORD OF THE WORLD

BY ROBERT HUGH BENSON (1907)

Book II, The Encounter, Chapter IV, Section III

(Note: The hero of the story, a young English priest, Fr. Percy Franklin, has gone to Rome to report to Pope John XXIV on what he has seen in England: the arrival of a leader named Senator (then President of Europe) Julian Felsenburgh. Felsenburgh is proposing global harmony, but leaving aside Christ. The Pope has responded by establishing a new “Order of Christ Crucified,” and has made Fr. Percy a cardinal. The Pope’s intent is for Percy to succeed him when he dies. Now, in England, Parliament has just passed a new “Bill of Worship” — identical to bills passed in Germany, Spain, Italy, and all other countries — requiring all citizens to attend a new liturgy four times each year, giving homage to a “Spirit of the World” under the titles of Maternity, Life, Sustenance, and Paternity. Catholic Mass will still be “allowed,” but all will be required to attend these new ceremonies, or face imprisonment… Oliver Brand, an influential Labour MP from Croydon, and his wife Mabel Brand, a quite “modern” British couple, are now discussing this mandatory new, post-Christan liturgy with a certain “Mr. John Francis” — formerly a Catholic priest — who has been asked by the new British Minister of Public Worship to take charge of (be Master of Ceremonies for) the first celebration of the ceremonies of the new humanist religion on October 1…)

“First,” he (Mr. Francis) said, “we must remember that this ritual is based almost entirely upon that of the Masons. Three-quarters at least of the entire function will be occupied by that. With that the ceremoniarii will not interfere, beyond seeing that the insignia are ready in the vestries and properly put on. The proper officials will conduct the rest… I need not speak of that then. The difficulties begin with the last quarter.” He paused, and with a glance of apology began arranging forks and glasses before him on the cloth.

“Now here,” he said, “we have the old sanctuary of the abbey. In the place of the reredos and Communion table there will be erected the large altar of which the ritual speaks, with the steps leading up to it from the floor. Behind the altar—extending almost to the old shrine of the Confessor—will stand the pedestal with the emblematic figure upon it; and—so far as I understand from the absence of directions—each such figure will remain in place until the eve of the next quarterly feast.”

“What kind of figure?” put in the girl.

Francis glanced at her husband. “I understand that Mr. Markenheim has been consulted,” he said. “He will design and execute them. Each is to represent its own feast. This for Paternity—” He paused again.

“Yes, Mr. Francis?”

“This one, I understand, is to be the naked figure of a man.”

“A kind of Apollo—or Jupiter, my dear,” put in Oliver.

Yes—that seemed all right, thought Mabel. Mr. Francis’ voice moved on hastily.

“A new procession enters at this point, after the discourse,” he said. “It is this that will need special marshalling. I suppose no rehearsal will be possible?”

“Scarcely,” said Oliver, smiling.

The Master of Ceremonies sighed. “I feared not. Then we must issue very precise printed instructions. Those who take part will withdraw, I imagine, during the hymn, to the old chapel of St. Faith. That is what seems to me the best.” He indicated the chapel. “After the entrance of the procession all will take their places on these two sides—here—and here—while the celebrant with the sacred ministers—”

“Eh?”

Mr. Francis permitted a slight grimace to appear on his face; he flushed a little. “The President of Europe—” He broke off. “Ah! that is the point. Will the President take part? That is not made clear in the ritual.”

“We think so,” said Oliver. “He is to be approached.”

“Well, if not, I suppose the Minister of Public Worship will officiate. He with his supporters pass straight up to the foot of the altar. Remember that the figure is still veiled, and that the candles have been lighted during the approach of the procession. There follow the Aspirations printed in the ritual with the responds. These are sung by the choir, and will be most impressive, I think. Then the officiant ascends the altar alone, and, standing, declaims the Address, as it is called. At the close of it—at the point, that is to say, marked here with a star, the thurifers will leave the chapel, four in number. One ascends the altar, leaving the others swinging their thurifers at its foot—hands his to the officiant and retires. Upon the sounding of a bell the curtains are drawn back, the officiant censes the image in silence with four double swings, and, as he ceases the choir sings the appointed antiphon.” He waved his hands.

“The rest is easy,” he said. “We need not discuss that.”

To Mabel’s mind even the previous ceremonies seemed easy enough. But she was undeceived.

“You have no idea, Mrs. Brand,” went on the ceremoniarius, “of the difficulties involved even in such a simple matter as this. The stupidity of people is prodigious. I foresee a great deal of hard work for us all…. Who is to deliver the discourse, Mr. Brand?”

Oliver shook his head. “I have no idea,” he said. “I suppose Mr. Snowford will select.”

Mr. Francis looked at him doubtfully. “What is your opinion of the whole affair, sir?” he said.

Oliver paused a moment. “I think it is necessary,” he began. “There would not be such a cry for worship if it was not a real need. I think too—yes, I think that on the whole the ritual is impressive. I do not see how it could be bettered….”

“Yes, Oliver?” put in his wife, questioningly.

“No—there is nothing—except… except I hope the people will understand it.”

Mr. Francis broke in. “My dear sir, worship involves a touch of mystery. You must remember that. It was the lack of that that made Empire Day fail in the last century. For myself, I think it is admirable. Of course much must depend on the manner in which it is presented. I see many details at present undecided—the colour of the curtains, and so forth. But the main plan is magnificent. It is simple, impressive, and, above all, it is unmistakable in its main lesson—”

“And that you take to be—?”

“I take it that it is homage offered to Life,” said the other slowly. “Life under four aspects—Maternity corresponds to Christmas and the Christian fable; it is the feast of home, love, faithfulness. Life itself is approached in spring, teeming, young, passionate. Sustenance in midsummer, abundance, comfort, plenty, and the rest, corresponding somewhat to the Catholic Corpus Christi; and Paternity, the protective, generative, masterful idea, as winter draws on…. I understand it was a German thought.”

Oliver nodded. “Yes,” he said. “And I suppose it will be the business of the speaker to explain all this.”

“I take it so. It appears to me far more suggestive than the alternative plan—Citizenship, Labour, and so forth. These, after all, are subordinate to Life.” Mr. Francis spoke with an extraordinary suppressed enthusiasm, and the priestly look was more evident than ever. It was plain that his heart at least demanded worship.

Mabel clasped her hands suddenly. “I think it is beautiful,” she said softly, “and—and it is so real.”

Mr. Francis turned on her with a glow in his brown eyes.

“Ah! yes, madam. That is it. There is no Faith, as we used to call it: it is the vision of Facts that no one can doubt; and the incense declares the sole divinity of Life as well as its mystery.”

“What of the figures?” put in Oliver.

“A stone image is impossible, of course. It must be clay for the present. Mr. Markenheim is to set to work immediately. If the figures are approved they can then be executed in marble.”

Again Mabel spoke with a soft gravity. “It seems to me,” she said, “that this is the last thing that we needed. It is so hard to keep our principles clear—we must have a body for them—some kind of expression—” She paused.

“Yes, Mabel?”

“I do not mean,” she went on, “that some cannot live without it, but many cannot. The unimaginative need concrete images. There must be some channel for their aspirations to flow through— Ah! I cannot express myself!”

Oliver nodded slowly. He, too, seemed to be in a meditative mood.

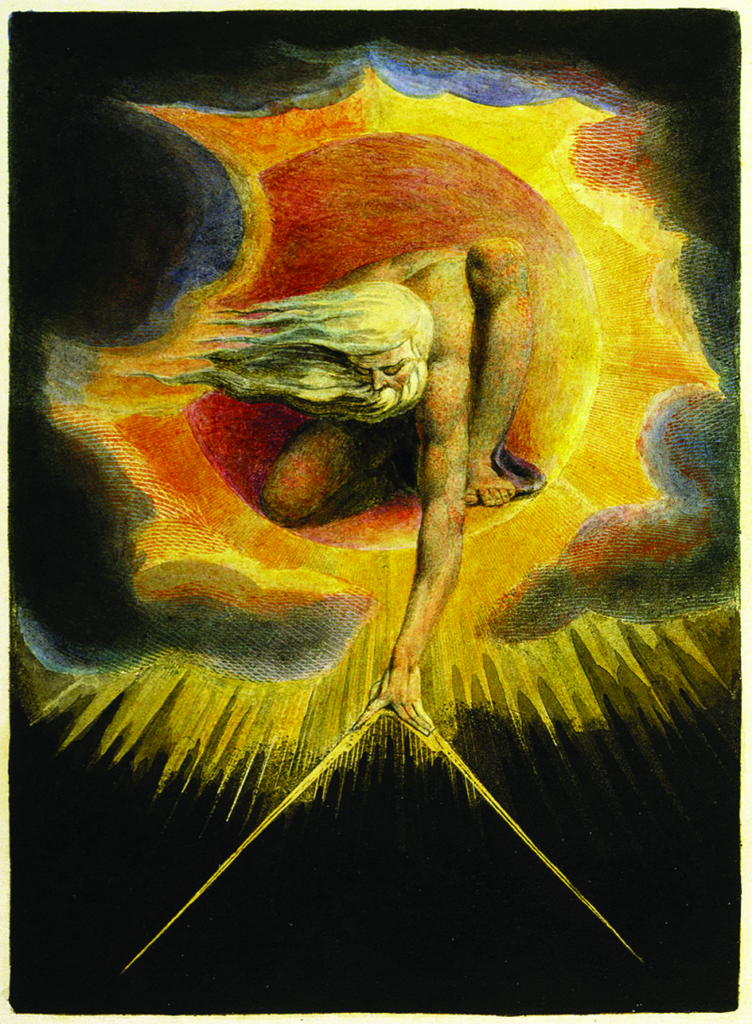

God as seen by the British poet William Blake as the Architect of the world in his 1794 watercolor etching Ancient of Days, now held in the British Museum, London. The name “Ancient of Days” is a name for God used by the Prophet Daniel: “I kept looking until thrones were set up, and the Ancient of Days took His seat; His vesture was like white snow and the hair of His head like pure wool….” (Daniel 7:9)

“Yes,” he said. “And this, I suppose, will mould men’s thoughts too: it will keep out all danger of superstition.”

Oliver bowed as he gathered up his papers.

Mr. Francis turned on him abruptly.

“What do you think of the Pope’s new Religious Order, sir?”

Oliver’s face took on it a tinge of grimness.

“I think it is the worst step he ever took— for himself, I mean. Either it is a real effort, in which case it will provoke immense indignation—or it is a sham, and will discredit him. Why do you ask?”

“I was wondering whether any disturbance will be made in the abbey.”

“I should be sorry for the brawler.”

A bell rang sharply from the row of telephone labels. Oliver rose and went to it. Mabel watched him as he touched a button—mentioned his name, and put his ear to the opening.

“It is Snowford’s secretary,” he said abruptly to the two expectant faces. “Snowford wants to—ah!”

Again he mentioned his name and listened. They heard a sentence or two from him that seemed significant.

“Ah! that is certain, is it? I am sorry…. Yes…. Oh! but that is better than nothing…. Yes; he is here…. Indeed. Very well; we will be with you directly.”

He looked on the tube, touched the button again, and came back to them. “I am sorry,” he said. “The President will take no part at the Feast. But it is uncertain whether he will not be present. Mr. Snowford wants to see us both at once, Mr. Francis. Markenheim is with him.” But though Mabel was herself disappointed, she thought he looked graver than the disappointment warranted.

(End, Book II, The Encounter, Chapter IV)

(To be continued)

Facebook Comments