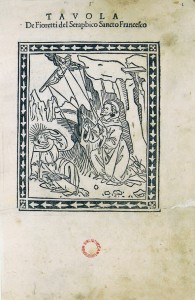

“I Fioretti,” or “Little Flowers,” an anonymous biography of St. Francis of Assisi composed at the end of the 14th century, probably in Tuscany

Two splendid exhibitions this spring concern the history of the book in Europe during the Middle Ages and Renaissance and its impact on European and thus world culture: I Libri Che Hanno Fatto l’Europa (The Books That Made Europe) on at Palazzo Corsini in Trastevere, Rome, until July 22 (Via della Lungara 10, Rome, entrance free, hours: Monday, Wednesday and Friday: 9 AM to 1 PM; Tuesday and Thursday 9 AM to 5 PM; Saturday and Sunday: closed) and Aldo Manuzio: il rinascimento di Venezia (Aldo Manuzio: The Renaissance in Venice) on until June 19 at the newly-renovated Accademia, Venice’s most important art museum (entrance fee: 6 euros, Monday 8:15 AM-2 PM, Tuesday-Sunday 8:15 AM-7:15 PM, free audio guide and splendid catalog [45 euros] both in English).

In these present times of economic crisis, political instability, and mass migration from Syria, Afghanistan, and Africa, Europe is struggling with a devastating identity crisis. In contrast, The Books That Made Europe, which looks at the birth of European culture through ancient manuscripts and the earliest printed books, extols the melting pot of cultures, which has shaped Europe.

The nearly 190 volumes on display, written in Latin, Greek, Chaldean, Arabic, and Hebrew, Oïl, French, and Italian between the 8th and 16th centuries, both manuscripts and printed, were chosen to show that culture is the unifying force of Europe. “If these volumes teach us anything today, it’s that Europe’s wealth lies in the plurality of its cultures,” said curator Roberto Antonelli at a press preview. The majority already belongs to the exhibit’s site, this magnificently frescoed library of the prestigious Biblioteca Corsiniana e dell’Accademia dei Lincei (Lincean Academy), the first European academy devoted to the natural sciences founded in 1603. Its core collection dates to the donation in 1733 by Pope Clement XII of his personal library to his nephew Cardinal Neri Maria Corsini. A public library since 1754, it conserves numerous precious manuscripts, the most complete collection of books printed by Sweynheim and Pannartz, the German typographers of the first books printed in Italy between 1465 and 1473, and numerous cinquecentine (books printed during the 1500s,) including many printed by Aldo Manutius.

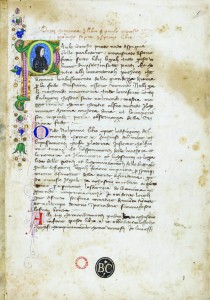

Paolo Orosio’s “Historiarum Adversum Paganos Libri VII,” or “The Seven Books of History agains the Pagans”

The loans are from other historically important public libraries in Rome: The Angelica, The Casanetense or Casanata, The Nazionale Centrale, and the Vallicelliana, as well as the Vatican Library (see my Interview with Father Raffaele Farina, ITV, July 2005).

The Books That Made Europe is divided into 5 macro-areas with 19 sections: The Classical-Christian Tradition with I. Trivium (the medieval university curriculum, based on that of ancient Greece: the study of grammar, logic, and rhetoric), II. Quadrivium (again based on the ancient Greek curriculum: the study of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy), III. Bible, IV. Auctores (ancient Roman authors), and V. Founding Fathers of the Church; Towards The New European Culture with VI. Encyclopedias and VII. Treatises of Science; The New European Culture with VIII. Law, IX. Aristotelianism, X. Hagiography and Didactic Literature, XI. Historiography, XII. Epic Poetry, XIII. Romance, XIV. Lyric Poetry, XV. Laudari and Mystery Plays; The First Canon with XVI. Dante, XVII. Petrarch, XVIII. Boccaccio, and Towards Modernity with XIX. Towards Modernity.

Sadly, but typically Italian, the forthcoming catalog to this tour-de-force exhibition will not published until the exhibition is about to close, and the wall panels and explanations for each volume are only in Italian. However, at the entrance the curators have graciously supplied visitors with a free pamphlet of explanations for each macro-area with a list of its important volumes in the English as well as the Italian versions.

For The Classical-Christian Tradition, the pamphlet explains that after the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 AD, for more than 1000 years, “knowledge and cultural education in Europe were almost exclusively assured through territorial structures and church schools inspired by the works and teachings of the ‘Fathers of the Church,’” in particular St. Augustine and St. Jerome, also “founders” of Classical-Christian culture, and by the Bible.

Of special note here is the exhibition’s very first entry, a 12th/13th century manuscript by 6th-century Latin grammarian Priscian, Institutio de arte grammatica, used as a grammar manual for over 1,000 years and often present in medieval and humanistic libraries, but even in Sigmund Freud’s. Another is an 8th-century manuscript, the oldest in the exhibition, of fragments of Gregory the Great’s Moralia in Job. This small codex originally contained Palimpsest fragments of the Codex Theodosianus, the compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire under the Christian emperors, scratched away to write Gregory the Great’s text on top. Moreover, Professor Armando Petrucci, paleographer and medievalist, recently found 38 strips of parchment from an incunabula containing the writings of St. Augustine placed there later to reinforce the binding. Also special is one of the c. 100 so-called “Atlantic” Bibles. Of enormous format and weighing over 40 pounds each, they were produced between the middle of the 11th century and the second half of the 12th century in Central Italy.

A 15th-century manuscript from Tuscany, “La Spagna”

The stars of the other macro-areas are:

from Towards the New European Culture: Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae, the greatest early Middle Ages encyclopedia about the origins of names and of things; Il Tresor, written by Dante’s teacher Brunetto Latini in Oïl, the first encyclopedia written in a modern language; the apex of Arab-Islamic encyclopedias in Arabic, Al-Safadi’s al-Wafi bi-al-wafayat, or “Encyclopedia of Illustrious Men,” about the V.I.P.s who lived between the foundation of Islam and the 14th century; Pliny the Elder’s’ treatise Naturalis Historia, printed by Johann of Speyer, among the first German typographers to work in Venice, on September 18, 1469; and Yahya ibn Zakariyya’ibn Abi al-Raga’s Nur al’uyun wa-gami’ al funun or “Treatise of Ophthalmology” in Arabic, and many other medieval medical texts.

from The New European Culture:

Law:

The jurist Gratian’s Decretum, the 12th-century text or the first complete try at organizing Canon Law, used until Pope Benedict XV’s reform in 1917. Peter Schöffer, Gutenberg’s disciple and successor in Mainz, printed this volume on August 13, 1472; one of the first editions of Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae, a compendium of all the main theological teachings of the Catholic Church and one of most influential works of Western literature, printed in Padua by Albrecht Stendhal on October 5, 1473.

Hagiography and Didactic Literature: A manuscript of Legendae sanctorum, a compilation by Jacopo da Varrazze of sacred stories about the lives of the saints and liturgical festivals, was extremely popular, counting over 1,000 manuscripts and 70 printed versions, not to mention the number of biographies of individual saints in the ever-growing use of the vernacular, examples being I Fioretti di San Francesco and Considerazioni sulle sacre stimmate, which opens with a woodcut based on Giotto of St. Francis receiving the stigmata. The latter remained very popular in Italian households until a few decades ago.

Historiography: Paulus Orosius’ masterpiece, Historiarum Adversum Paganos Libri VII, on display here in its Italian translation by Bono Giamboni, is considered to be one of the books with the greatest impact on historiography during the period between antiquity and the Middle Ages, as well as being one of the most important Hispanic books of all time. “Its importance,” Wikipedia explains, “is the fact that Orosius was the first Christian author to write not a church history, but rather a history of the secular world interpreted from a Christian perspective. Read and copied without interruption through the Middle Ages and Renaissance, without a doubt it’s one of ‘the books that made Europe.’”

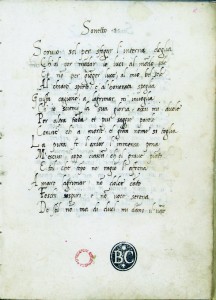

A manuscript of Petrarch-inspired poems by Vittoria Colonna

Epic Poetry: Attributed to the Florentine Sostegno di Zanobi and likely composed between 1350 and 1360, La Spagna, one of the most famous works of the Carolingian tradition in Italian, is an adaptation of the story of Charlemagne’s battles in Spain and the adventures of his nephew, the Paladin Orlando. It includes the tale of Orlando’s duel with Ferraguto and his ultimate death at Roncesvalles. It was an important inspiration for Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, also on display.

Romance: The Vatican’s manuscript Reg. lat. 1725 contains Chrétien de Troyes’ four very famous novels in verse including Yvain, the Knight of the Lion and Lancelot. Chrétien was a late 12th century poet and trouvère known for his work on Arthurian subjects. His work represents some of the best-regarded medieval literature and has inspired authors for centuries with his use of structure, particularly in Yvain, seen as a step towards the modern novel. Also on display here is one of the 300 surviving manuscripts of the most successful medieval allegorical romance, Roman de la Rose.

Lyric Poetry: Side by side here are a manuscript of the first anthology of poems inspired by Petrarch and written by a woman, Marchioness Vittoria Colonna (1492-1547), one of the most popular poets of 16th-century Italy and a friend of Michelangelo, with whom she exchanged verses, as well as the first printed volume of her poems and thus of poems written by a woman.

from The First Canon:

Dante: includes several editions of The Divine Comedy, with a commentary by humanist and prolific writer Cristoforo Landino and illustrations by Botticelli, printed in Florence on August 30, 1481; another with a commentary by Jacopo della Lana, printed in Venice by Johann and Wendelin of Speyer, and a manuscript handwritten by the poet Antonio Pucci and paginated by Boccaccio.

Petrarch: includes Petrarch’s personal copies of Virgil with his marginal notes and of Cicero’s Tusculanae disputationes, also with his marginal notes.

Boccaccio: a manuscript of Teseida, his long epic poem, which is the main source for “The Knight’s Tale” in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and the original source of Two Noble Kinsmen, a collaboration between Shakespeare and John Fletcher.

Francesco Colonna’s “Hypnerotomachia Poliphili,” printed by Aldus Manutius in Venice

The first printed book of poems by a woman

from Towards Modernity:

Among this last section’s selection of early printed books are Poliziano’s personal copy of Catullus, Tibullus, Statius, and Propertius with his marginal notes, printed in Venice in 1472 by Johann and Wendelin of Speyer; Lorenzo Valla’s Elegantiae linguae latinae, also printed in Venice by Nicolaus Jenson before 1471, a manual for his contemporaries on how to reproduce the elegant style of the ancients in modern writings; Erasmus of Rotterdam’s Folly, printed in Venice by Aldus Manutius’ heirs and Andrea Torresano, in 1515, shortly after Aldus’ death; and Francesco Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, printed by Aldus Manutius in Venice in December 1499.

Long considered to be the most beautiful Renaissance printed book, the first one with illustrations (172 refined woodcuts), this volume, a mysterious arcane allegory/love story entitled in English Poliphilo’s Strife of Love in a Dream, and the art it inspired, are the subject of Section III, “A Dream of Erotic Strife” of Aldo Manuzio: The Renaissance in Venice. It’s the only contemporary fiction Manutius printed.

This exhibition, divided into eight sections: “From Rome to Venice,” “Manutius’ Enterprise and Impresa,” “Manutius and the Greek Legacy,” “A Dream of Erotic Strife,”“Domestic Classics,” “All’Antica Devotion,” “Rediscovering Country Life,” “Modern Classics,” and “Divine Proportions,” commemorates the 500th anniversary of this unique publisher’s death on February 6, 1515. It successfully shows how the books Manutius published not only influenced the other visual arts being produced in Renaissance Venice, but also changed the world.

Vittore Carpaccio’s “St. Ursula and the Pilgrims Meet Pope Cyriacus Outside Rome”

As the opening wall panel tells us, “In the late fifteenth century printed books began to replace manuscripts. This was an epoch-making change, comparable to the digital revolution of our own age. And Venice was its Silicon Valley. From 1495 to 1515 Aldus Manutius (1449-1515) published around one hundred books of a previously unrivalled beauty. They were mainly Greek and Latin classics, impeccably edited with a very refined layout designed to facilitate reading.”

Born in Bassiano, a small town in the Papal States, some 60 miles south of Rome, to a wealthy family, Manutius was educated as a humanistic scholar, studying Latin in Rome and Greek in Ferrara before becoming a tutor himself in 1480 to Princes Alberto and Leonello Pio, the nephews of Manutius’ illustrious old friend and fellow-humanist Giovanni Pico.

It is not clear why Manutius moved to Venice between 1489 and 1490, but at first he probably continued his work as a teacher, as shown by the publication of his Latin grammar Institutiones grammaticae Latinae, printed on March 8, 1493 by the already successful typographer Andrea Torresano, who would soon become Manutius’ business partner and later his father-in-law. Possibly Manutius’ interest in printing developed gradually due to his dissatisfaction with the poor quality of the texts and books on which he had to rely as a teacher. In what better place than the publishing capital of Europe with its 150 presses, also the home of one of the greatest libraries of Greek (482 mss.) and Latin (264 mss.) literature, which Cardinal Bessarion (1403-1472) had bequeathed to the Senate of Venice in 1468!

Cima da Conegliano’s “Saint Helena”

As the exhibition’s website www.mostraaldomanuzio.it tells us: “The founding of the Aldine press dates from 1494. The first work was the Greek grammar Erotemata by Constantine Lascaris, printed between February and March 1495. Thanks to the generosity of his former pupil Alberto Pio, the first tome of Aristotle’s works followed in 1495, which was to be completed in 1498 with five folio volumes.” In the preface of the first volume Manutius had written: “It is our lot to live in turbulent, tragic, and tumultuous times. Times when men more commonly turn to arms than books. And yet I shall have no rest until I have created a plentiful supply of good books.”

Lorenzo Lotto’s “Allegories of Virtue and Sin”

At first intending to publish only high-quality Greek classical texts for the diffusion of Greek culture, his principal objective, Manutius a few years later expanded his offerings to include Latin and Italian classics. However, more than once he had to modify his titles or shut down his business because of political unrest and wars. Besides Aristotle, his Greek authors included Aristophanes, Theocritus, Hesiod, Thucydides, Sophocles, Herodotus, Xenophon, Euripides, Demosthenes, Lucian, Plutarch, Plato, and Pindar, among others.

Beginning in 1501, after a considerable drop in requests for Greek texts, Manutius began to print Latin texts, first Virgil in April, followed by Persius and Juvenal, Martial, Cicero, Ovid, Catullus, Tibullus and Propertius, not to mention Italian classics like Petrarch’s Cose Volgari, and the following year Dante’s Terze Rime. His most prestigious contemporary client was Erasmus of Rotterdam, who lived with the Manutius/Torresano family between 1506-9, while Aldus was editing and publishing his Adages, a compendium of Greek and Roman mottoes that became the first Europe-wide bestseller. It is here that Erasmus relates that Manutius’ logo of a dolphin curled around an anchor came from a coin of the Roman Emperor Titus that Pietro Bembo, the great humanist man-of-letters, had presented to Manutius.

As the publisher’s Marsilio accompanying pamphlet tells us, “the extensive publication of classical texts also had repercussions on the art world. Lucian’s written descriptions of lost masterpieces of antique painting, such as Apelles’ Calumny or The Centaur Family by Zeuxis, were borrowed from the pages of books and made into miniatures, prints, sculptures, and paintings.” Furnishings, drawings by Dürer and paintings by Vittore Carpaccio, Lorenzo Lotto, Giorgione and Bellini among many others, with increasingly allegorical and mythological subjects clearly of classical inspiration, began to enter cultured Venetian homes, as did portraits of their owners or of important saints like Cima da Conegliano’s St. Helena with local countryside backgrounds. So did sculptures with rustic themes inspired by Theocritus or Virgil.

For his Latin and Italian volumes, Manutius used a new typeface, italics, and new pocket editions (defined in his 1503 catalog as “libelli portatiles in formam enchiridia”). With this smaller size his intention was not so much to lower prices as to encourage a different use of the book, up to then limited to the clergy, professors, and scholars. With his easily portable “pocket-editions” he wanted to enter into the lives of people. He’d not only revolutionized the book itself, but created a reading public who read for pleasure.

Titian’s “Portrait of Jacopo Sannazaro” holding an Aldine book

Parmigianino’s “Portrait of a Young Man” holding an Aldine Petrarch

In fact, the exhibition ends with four portraits from the first decades of the 16th century: two men, by Titian and Parmigianino, and two women, by Palma il Vecchio and Lorenzo Lotto, all four holding Aldine pocket books. Often with attractive customized bindings, these little volumes had become must-have fashion accessories.

Besides inventing italic type and introducing “inexpensive” books in small format, Manutius established the modern use of the semicolon, and developed the appearance of the comma. After his death in 1515, Aldus’ wife and her father managed the press until his son Paolo (1512-1574) took over. His grandson Aldo then ran the firm until his death in 1597. Today antique books printed by the Aldine Press in Venice are referred to as Aldines. The most nearly complete collection of Aldine editions ever brought together was in the Althorp Library of the 2nd Earl of Spencer, now in the John Rylands Library, Manchester, England. For further reading: Barolini, Helen, Aldus and His Dream Book (New York, Italica Press, 1992) and Davies, Martin, Aldus Manutius, Printer and Publisher of Renaissance Venice (1995).

Facebook Comments