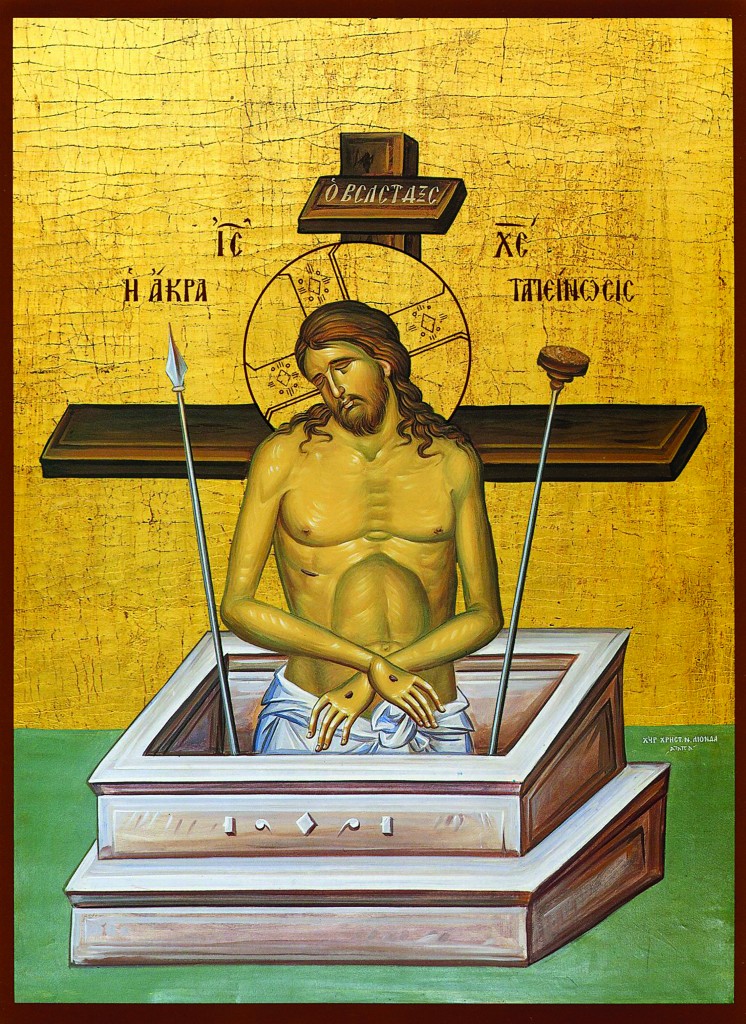

The icon of “Extreme Humility” depicting the King of Glory in His Tomb

One of the most powerful icons for the Lenten season is that depicting the King of Glory in His tomb, commonly called “Extreme Humility.” The grave is the great human equalizer, of course; princes and paupers alike must descend into death and experience the corruption of the flesh. An honest contemplation of the grave must necessarily lead to a humble acceptance of the imperfect human condition.

Yet, humility is the most elusive of virtues. We strive for humility, and then once we achieve it we find ourselves proud of our spiritual victory and must begin again, in a never-ending cycle of futility. St. John Climacus points out the only solution to the dilemma, the attribution of any victory over pride to Christ rather than the self.

Indeed, there can be no greater example of humility than that of the immortal God Who accepts even the tomb in an utter abnegation of the self. Thus this month’s image, that of the King of Kings reduced to the tomb and reduced in the most humbling of circumstances, death as a common criminal on the cross.

There is a further lesson in the icon, common to all icons but perhaps most powerful here. The tomb is depicted as a sarcophagus, an oddly shaped object of flawed symmetry; the perspective of the tomb is distinctly contrary to all the rules of perspective in Western art. The use of geometrical perspective in the Western tradition serves to draw the eye into the picture, carrying the thought of the viewer into the scene depicted. An analysis of such a picture reveals the lines of perspective leading the viewer’s eye to a specific place in the painting called the “vanishing point.” All the lines of perspective converge here, where the eye can travel no further because the scene vanishes into the distance. The viewer is drawn into the picture by visually following the lines, thus becoming an active participant in the painting.

Not so with the icon! The lines of perspective in this image cannot lead the eye into the image at all and in fact cannot converge as a vanishing point anywhere but to the front of the icon. The eye is further blocked by a solid background behind the figure of Christ, serving to reflect attention back from the image. In short, visually it is impossible for the viewer to “enter” the icon in the usual artistic sense. Of course, there is a profound theological purpose at work.

The technique in play is called “inverse geometry,” a complete reversal of the theory governing Western art. The spiritual principle at work is that of the Good Shepherd, He Who actively enters the world in search of the lost ones who so desperately need to be found. So, too, the icon is designed such that the image is throwing itself out of the flat surface, following the lines of perspective which converge in the human heart standing before the icon, ready to be found! The image enters the soul of the lost and brings to it the resting place of a safe pasture. The icon itself is the active artistic element and the faithful are obviously called to humbly submit to the working of the Spirit through the image.

The specific lesson of Extreme Humility is thus clarified: the humility we seek cannot be found by any effort of our own but can only be achieved by allowing the humility of Christ to take up residence in our hearts. Our attempts at conquering pride are poor, pathetic things, doomed to failure at the outset, an instance of that “vanity of vanities” spoken of by Ecclesiastes. The only certain road to humility lies along the path of the cross and tomb of Christ Himself.

— Robert Wiesner

Facebook Comments