“The Casting Out of Eden of Adam and Eve,” by Giusto De’ Menabuoi, in the Baptistry of Padua, Italy

Our immortal souls are joined to mortal bodies. How can this be? A thought-provoking philosophical reflection on human nature by the great Belgian philosopher Dr. Alice von Hildebrand

At age eleven, I was privileged to discover Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), one of the very great names in French literature, and I started reading his Pensées. I was so impressed and moved by their depth and literary beauty that I bought the book, memorized several of the “thoughts,” and kept repeating them to myself while walking along the Belgian sea shore, as the summer sun was setting over the ocean. One that struck me particularly was the following: “Man is the most mysterious object in nature.” Being a human person, I felt challenged to meditate on the “mysterious “ character of my nature.

This concern will set the framework of my essay. Human beings are persons made to God’s image and likeness, but we also have a body that neither God nor angels have. To have a body clearly does not prevent us from being “persons” — for one cannot be more or less persons, but one can be more or less perfect persons — but it sheds light on Pascal’s remark: the most “mysterious” object in nature. Like animals, we have a body, but this body is a body “inhabited” by a soul, and this is a factor of crucial importance: for an animal body animated by a spiritual soul will inevitably be, in more ways than one, radically different from a purely animal body.

It is the body of a person, that is to say, every single facet of this living piece of flesh, that will be marked by its union with a spiritual soul. When men eat, their eating should be preceded by a prayer thanking God for this gift. Our breathing, our working, our sleeping should all have the mark of our personhood: this is the secret lived by the saints. None of their activities is unrelated to God, in adoration and thanksgiving. The body’s union with the soul, far from drawing us down to the animal level, should on the contrary elevate our flesh and have it join the soul in expressing love and gratitude to our Creator. Our adoring God, for example, should be manifested by the physical acts of bowing and kneeling, something beautifully evident in the great Catholic and Orthodox liturgies.

That we have been granted the unfathomable gift of being persons calls for gratitude and carries the responsibility of living up to our calling. The French say rightly, “Noblesse oblige” (“nobility obliges”), but the fact that this soul is “incarnated” challenges us to face a serious metaphysical question: “How can this be?”

One classical temptation shared by both Gnosticism and Manichaeism is to endorse dualism, i.e., a philosophy denying that man is both body and soul; their claim is that man is essentially only a soul. The soul is good and pure; but the body is evil, in fact the source of all evil. It sounds reasonable, and offers an easy solution to the problem of evil: the body is the guilty one. (This philosophy was for many years endorsed by the young Augustine.)

Today, this grave error is not in the foreground, even though errors and heresies are chronic and resurface periodically. But today the Zeitgeist favors materialism, denying the personhood of man, and therefore any essential difference between him and animals. Man is only a body, it says, whose brain is more developed that that of other mammals, but he is in no way metaphysically superior to them. According to Peter Singer, professor at Princeton University, a healthy chimpanzee is much superior to a handicapped child.

“St. Augustine” by Francisco Goya

Both Manichaeism and materialism have been condemned by the Church, but still She faces a mystery, namely, that man is both body and soul. What is their relationship?

A living body is definitely something that we share with animals: but this similarity can cheat us into overlooking the abysmal difference separating us from them. Having a soul is the dividing line between persons and non-persons. Having a body distinguishes us from angels, but does not at all affect our personhood: we share this honor with them. Every single one of our perceptions manifests our personhood: a beautiful sunset brings tears to our eyes; sublime music has the same effect. Animals hear the sounds; they do not perceive their beauty. They will respond to very loud sounds, but would not perceive the aesthetic value of a crescendo. Animals reproduce themselves, but human reproduction, as intended by God, is a domain where the crucial difference between man and animals manifests itself most strikingly: there is an abyss between animal instinct and human love. It is of crucial importance to shed some light on this question — a question that animals do not and cannot raise.

I daresay that it is, paradoxically, precisely man’s very body that points to the radical difference between him and animals. Another Pensée of Pascal sheds light on this paradox. He tells us that Man is but a reed, the weakest in nature, but he is a thinking reed. The universe need not arm itself in order to destroy him; a vapor or drop of water suffices to kill him, and Pascal ends by reminding us that the universe has no awareness of its “superiority” over man, whereas man — the weakest reed in nature — knows that he is dying: the crushing victory of mind over matter.

When we say “man” we obviously refer to both male and female: two different genders of equal dignity, but essentially complementary; the fullness of human nature is to be found in male and female. Before original sin, there was perfect harmony between the Creator and the creatures: the latter knew that they were given existence as a pure gift, were grateful for it, and realized it was not only a strict obligation but also an honor to obey their Creator.

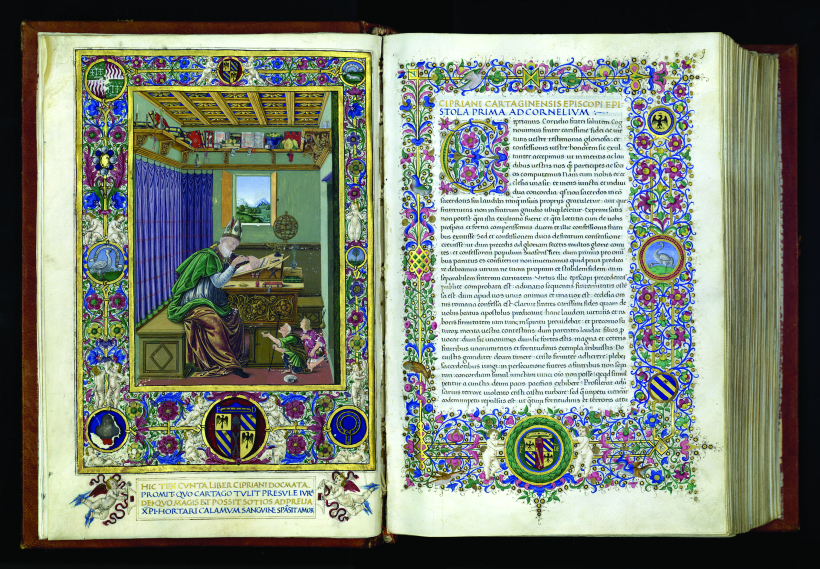

Detail from “The Resurrection of the Flesh,” by Luca Signorelli, now in the Duomo of Orvieto, Italy

Alas, tempted by pride (“Eritis sicut dii” — the flattering words of the serpent, “You shall be as gods”), man disobeyed his loving Creator. The consequences were fearful: not only was there a rupture between Creator and his human creatures — this crevasse was so deep that it could only be bridged by God himself: man needed a savior — but this sin also gravely affected the relationship existing between man and woman. Up to that time, they were singing a duet of gratitude, completing Adam’s solo when he first perceived Eve and joyfully exclaimed, “Flesh of my flesh, blood of my blood”: she was worthy to be his bride.

To quote St. Augustine, every sin brings about its own punishment. The moment our first parents sinned, they realized they were “naked,” which clearly means that the beautiful female body that up to now called for Adam’s admiration and awe, had become an object of lust and no longer a noble gift having a deep meaning both as an expression of love — which desires union — and as a door to fruitfulness. From this moment on — and alas, today more than ever — the sexual sphere became one of the most powerful attractions to sin.

Detail from “The Resurrection of the Flesh,” by Luca Signorelli

Last but not least, the perfect harmony that God had created between body and soul was severed, and now, alas (we all know but too well that the body keeps revolting against the soul) has become a source of temptation. The soul’s revolt against God is now duplicated with the body’s defiance of the legitimate commands of the soul: concupiscence is a fact that we have to contend with as long as we live, and explains why a St. Benedict threw himself into a thorny bush. Aping Satan, it keeps saying to the soul: “Non serviam” (“I will not serve”).

Let me limit myself to mentioning sloth, so powerfully expressed in Goncharov’s great novel, Oblomov — a man who ruined his life because he could not get out of bed. Or gluttony, illustrated in Rabelais’ Gargantua et Pantagruel. Or the very many plays and novels where the “hero” is devoured by pride and ambition (let us think of Macbeth or Richard the Third) and brings about his own downfall.

Born ante lucem (“before the light,” i.e., 400 years before Christ), Socrates could not possibly conceive the beautiful duet that body and soul were meant to play and did play before the fall. All he knew was that there was an ongoing war between them, the body often obstructing the soul’s way to truth by constantly distracting men from what should be their one great concern. To quote Socrates: “I am interested in nothing except knowing the truth” (Euthyphro). How many men can sincerely claim that this is their one great concern? Money-making, fame, power, enjoyment: these are the things that attract a high percentage of us, whether males or females. How right Plato was when he wrote that man was his own worst enemy (Republic, Book I).

Socrates also knew that shortly after death the human body decomposes and is fast reduced to dust and ashes. Can one wonder why this noble thinker, joyfully convinced of the immortality of the soul, viewed death as a liberation? Is it fair to accuse him, and his spiritual son Plato, of dualism? The gift of faith tells us that the body will be resurrected at the end of time and reunited with the very same soul. When the body dies, reduced to dust, it is inconceivable that it misses the soul. And if the soul enjoys the beatific vision, how could it possibly miss the body? Yet, a soul without a body is not a full human person.

Let me repeat: this is a mystery that fully justifies Pascal’s claim; man is the most mysterious object in nature. How can an “incomplete” human person be fully happy? And if it is not, it seems that accepting “dualism” is justified.

It is a mystery but it seems to me that in this specific context it is legitimate to use the term “temporary dualism” — a dualism which does not deny the essential unity of body and soul, a dualism which while fully real, will end when “time is no more.” That in statu viae (“in the condition of being on the way”) our body can be a heavy and unwelcome burden justifies the worlds of St. Paul: “Who will deliver me of this body of death?” (Romans) The beloved St. Teresa of Avila — whose life from her 20th year was burdened with painful physical problems that made her daily life a cross — utters similar words. And yet, this does not entitle us to deny that God has created us body and soul.

Now I come to the heart of my problem — which is more a mystery than a problem: the immortality of the soul, the existence of which is not affected by the death of the body. We know through our faith that at the moment of death, God will judge us according to the state of our soul when it is severed from its body. And where is this body? Reduced to a handful of dust. How is one to believe that a handful of dirt was the body of a beloved person? Yet our faith tells us that when all bodies will be resurrected we shall have the very same body that we had during our lifetime, though no longer afflicted by original sin — if saved, we will have a totally spiritualized and transfigured body, i.e., impassible, subtle, agile, and luminous. (I prefer not to mention the bodies of those who, through their own fault, are damned.)

Early Christian philosophy was strongly influenced by Plato — one of the greatest gifts that ancient Greece has left us. He was highly praised by the Fathers of the Church who dubbed him “a preparer of the ways of Christ.” This praise was endorsed by St. Augustine whose philosophy and theology strongly marked Christian thought until the XII century.

One of the keys to the Socratic-Platonic philosophy is that the body is the prison of the soul, and that at the moment of death, the latter —being blessed with immortality — is finally liberated from a companion that has caused him much travail. Plato, in his great dialogue Phaedo, poignantly relates the death of his beloved mentor. He found moving words to express his love, gratitude and admiration for this “gift” to the Athenian people: “He was the justest, wisest, best man I have ever known.” He who has read the Apology is bound to be deeply moved by the words of a man who, condemned unjustly, faces his “goodbye” to his earthly life so peacefully, a peace possible only because it is based on the inner conviction that his soul was immortal, and that truth and justice — alas, so often trampled upon on this earth — will gloriously prevail. By contrast, how horrible is the death of those convinced that when their bodies die, they will face the horror of nothingness: “E poi niente” (“and then nothing”).

Both Socrates and Plato were “pagans,” but it is crucial to remember that these words are ambiguous: they can refer either to a world before the coming of Christ, or to those not acquainted with his message; or to those who, having received his message, rejected it and apostasized. Often in our society, we mean by “pagan” an immoral Weltanschauung inevitably tainted with serious errors (pagan immorality), but in calling Socrates or Plato “pagans” we clearly refer to people who lived ante lucem but, deprived of the magnificent gift of Revelation, were still truth-loving and truth-seeking individuals. They were not granted the unfathomable gift of revelation but would certainly have accepted it had they received it. This explains the famous words of Kierkegaard: “I know that Socrates was not a Christian; but I also know that now he has become one.”

Plato (left, with the white beard, pointing upward) and Aristotle (pointing down) in “The School of Athens” by Raffaello Sanzio in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican Museums

Reflecting upon Socrates’ peaceful conviction that his soul would escape death, it should be obvious that, for him, the union of body and soul is a mismatch: that an immortal soul, purely spiritual, free from space and time, should be tied to a material body, the prisoner of time and space, running toward death from the very moment of its conception, is metaphysically shocking. How can this be?

The Platonic answer is that this union is purely temporary. The body is condemned to death; the soul is immortal. That is the legacy he left us. Let us not forget, however, that Plato could not possibly conceive how body and soul related at the moment of their creation when Adam expressed his delight upon perceiving the one made for him, the one who was meant to be his wife, the one enchanting and complementing him: “Flesh of my flesh; blood of my blood.”

The union of body and soul in our first parents spoke eloquently of divine creativity: how beautiful that the Divine Artist had united matter and spirit and that they clearly harmonized in human persons. For Plato, who only knew of the relationship between soul and body after original sin, it was inconceivable that the body joined the soul in singing the same beautiful theme of praising God.

When, after a dramatic struggle, poignantly related in his Confessions, Augustine liberated himself from the chains of Manichaeism — a radically dualistic philosophy — and being gloriously “defeated” by grace, found his way to the Catholic Church, he was inevitably challenged to re-examine his previous views. It must have become luminous to him that original sin had not only disrupted the loving bond existing between God and His creatures made in His image and likeness, but, moreover, had also gravely harmed the relationship that God had created between Eve and Adam, and also the one existing between body and soul.

An immortal soul closely united to a mortal body forces us to acknowledge that man’s existential situation is a mystery: mortality and immortality are in each and every one of us. Who is man? St. Augustine was keenly conscious of this and sheds light on his famous words: “I, the soul.” Personhood is a promise of immortality, but the death of the body is an undeniable fact. This “divorce” is so dramatic because of the incredibly close union (the soul influences the body; the body has an impact upon the soul) and this fact creates a totally new situation which is metaphysically baffling: man is a mystery not only to others, but also to himself. For when a soul dies in the state of grace and is granted the contemplation of God, can it possibly miss the body and “suffer” from its severance from what St. Francis called “Brother Ass”? Did not St. Philip say to Christ: “Show us the Father, and ‘sufficit nobis’ (it will be enough for us)”? To see God is the total fulfillment of man’s desires. How can it be even conceivable that the soul will miss its body when it contemplates God?

And yet a body essentially belongs to our being a human person.

This great mystery seems to justify, if properly understood, the word “dualism.” It is a de facto dualism which must be sharply distinguished from a metaphysical dualism — a denial that man was created both body and soul — a view that our Faith denies. In the Credo recited in many Masses, we express our faith that the body will one day rise from the dead; but two things must be underlined: first that during the time of their separation, the existence of the soul is in no way affected or threatened; and secondly, that when the body will be resurrected, it is will be a totally spiritualized body, freed from the laws of matter, and will be characterized by clarity, subtlety, agility and impassibility: that is, it will be above suffering.

Let me repeat: The very serious philosophical question of the relationship between body and soul is to be examined on two fronts: first, and this is clearly stated in Genesis: man is made up of a body and a soul.

But, after original sin, this question was complicated by the fact that body and soul are at war with each other. If one concentrates on the first question: dualism is to be mercilessly thrown out of court.

If one’s concern is the existential situation that we daily face, one can speak of a “dualism”: the one between spirit and flesh.

Dr. Alice von Hildebrand

This explains the poignant words of St. Paul: “Who shall deliver me from this body of death?” echoed by St. Teresa of Avila referring to her body as her mortal enemy. We are “split” beings, and only the saints are “unified.”

Part Two of Dr. von Hildebrand’s essay will appear in the next issue of ITV.

Facebook Comments