By Lucy Gordan

Inside the Vatican readers for certain know of Pope Francis’ two unprecedented acts to pray for the end to the coronavirus pandemic. The first was his unannounced pilgrimage on the afternoon of Sunday, March 15th, to the Basilica of St. Mary Major and to the Church of San Marcello al Corso; the second the moving prayer service at sundown on March 27 in an eerily empty St. Peter’s Square. Both times he prayed before two religious artifacts, particularly important to Romans and to himself: the icon of Salus Populi Romani and the “miraculous crucifix.” Here’s why…

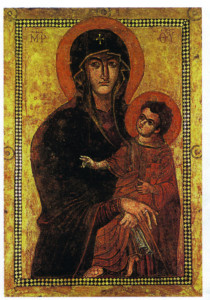

Pope Francis’ special devotion to the Salus Populi Romani (Salvation of the People of Rome) is well documented. Barely 12 hours after his election (the next morning even before he’d collected his personal belongings from the House of Hospitality Paul VI), he slipped out of Vatican City and headed to the Basilica of St. Mary Major. Here the new Pope prayed to Our Lady asking for her support on how to guide the Roman Catholic Church.

Since then he has continued to visit this icon on major Marian feast days. He also has made a point to stop in for a prayer both before and again after his, as of now, 32 apostolic trips abroad. The first one was to Rio de Janeiro from July 22-29, 2013 for World Youth Day. He brought with him a copy of Our Lady’s icon to be carried in procession, a tradition started by Saint John Paul II during World Youth Day celebrated in Rome in 2000.

In her article “Pope’s Love Affair with Mary Hits a New High with 67th Roman Visit,” published in Crux in January 2019, senior correspondent Elise Harris reported that Pope Francis had visited his beloved icon roughly 10 to 15 times a year since his election on March 13, 2013. But since her article you have to add several visits due to several more apostolic trips in 2019: Panama, 23-27 January; United Arab Emirates, 3-5 March; Morocco, 30-31 March; Bulgaria and North Macedonia, 5-7 May; Romania, 31 May-June 2; Mozambique, Madagascar and Mauritius, 4-10 September; and Thailand and Japan from 20-26 November.

However, Pope Francis’ most recent prayer at the altar below the icon reflects not only his personal spirituality, but also how seriously he takes his role as “shepherd” of the Roman diocese. On Sunday March 15, the Third Sunday of Lent, at approximately 4 p.m., unannounced, he slipped out of Vatican City again to visit the Salus Populi Romani. This time his objective was to show his closeness to all those suffering because of coronavirus and to implore Mary’s special protection so as to end the pandemic.

According to legend, the icon of Salus Populi Romani (c. 46 inches tall by 31 inches wide) was painted by St. Luke himself and brought from Jerusalem to Rome by St. Helena during the fourth century. It’s also said that it was Pope Gregory the Great who brought this icon to St. Mary Major in 590 as part of a procession during Eastertime, praying for an end to one of the deadliest plagues in Rome’s history. Nearly 1,000 years later another plague in Rome is said to have ended when Pope Pius V carried the Salus in procession to St. Peter’s Basilica. In 1571 the same Pope prayed to her for a victory in the Battle of Lepanto.

According to legend, the icon of Salus Populi Romani (c. 46 inches tall by 31 inches wide) was painted by St. Luke himself and brought from Jerusalem to Rome by St. Helena during the fourth century. It’s also said that it was Pope Gregory the Great who brought this icon to St. Mary Major in 590 as part of a procession during Eastertime, praying for an end to one of the deadliest plagues in Rome’s history. Nearly 1,000 years later another plague in Rome is said to have ended when Pope Pius V carried the Salus in procession to St. Peter’s Basilica. In 1571 the same Pope prayed to her for a victory in the Battle of Lepanto.

In 1605 Pope Paul V Borghese commissioned the chapel in St. Mary Major, the icon’s home since 1613, and in 1837 Pope Gregory XVI invoked her to put an end to a cholera epidemic. But after Pius V, the next pope to visit the icon in situ was Pius XII in 1950 after he’d proclaimed the dogma of the Assumption of Mary into heaven. As cardinal he’d celebrated his first Holy Mass with the icon on April 1, 1899. He paid homage to the icon again in 1954 when he crowned it in St. Peter’s Square for the centenary of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception.

In 1931, at the wishes of Cardinal Bonaventura Cerretti, the then-archpriest of St. Peter’s Basilica, and of Bartolomeo Nogara, the then-director of the Vatican Museums, the icon underwent its first restoration. The principal intervention was the removal of a silver covering of the entire icon except for the faces and head and shoulder of the Madonna and baby Jesus. Gregory XVI had added the silver foil in 1838 to be able to attach two new crowns. After this restoration, besides the two new crowns, a new cross was added to the Madonna’s necklace of three amethysts, four topazes, and two aquamarines. The missing diamonds of the 12-pointed star were added and the star was attached to the Madonna’s shoulder. (All the icon’s jewels were removed in 1988 and are on display in the Treasury of St. Mary Major.)

In 2017 the icon underwent a second state-of-the-art restoration and conservation in the Vatican Museums. The procedures used included infrared and ultraviolet spectroscopy and reflectography as well as x-rays, pigment studies using Raman and xrf analysis, and radiocarbon dating. These examinations were followed by refilling holes caused by insects; restoration of its golden halo damaged by corrosion; restoration, re-highlighting and repainting various parts of the image; varnishing its back; and strengthening its frame. Morphological studies revealed that the central panels were made of lime wood and the frame of ash.

The radiocarbon exams dated the wood, with more than 80% certainty, to from the end of the 9th century to the beginning of the 11th for the central section, and from the end of the 10th and the beginning of the 11th for the frame, so that its historical origins are still shrouded in mystery.

When the icon returned from the Vatican Museums to St. Mary Major, Pope Francis officiated at a Pontifical Mass in her honor on January 28, 2018, the 405th anniversary of her translation to the Basilica. After its 2017/18 restoration the Salus Populi Romani is not allowed to leave St. Mary Major; the icon on the steps of St. Peter’s during Pope Francis’s unique prayer service to end the coronavirus pandemic on March 27th was a copy.

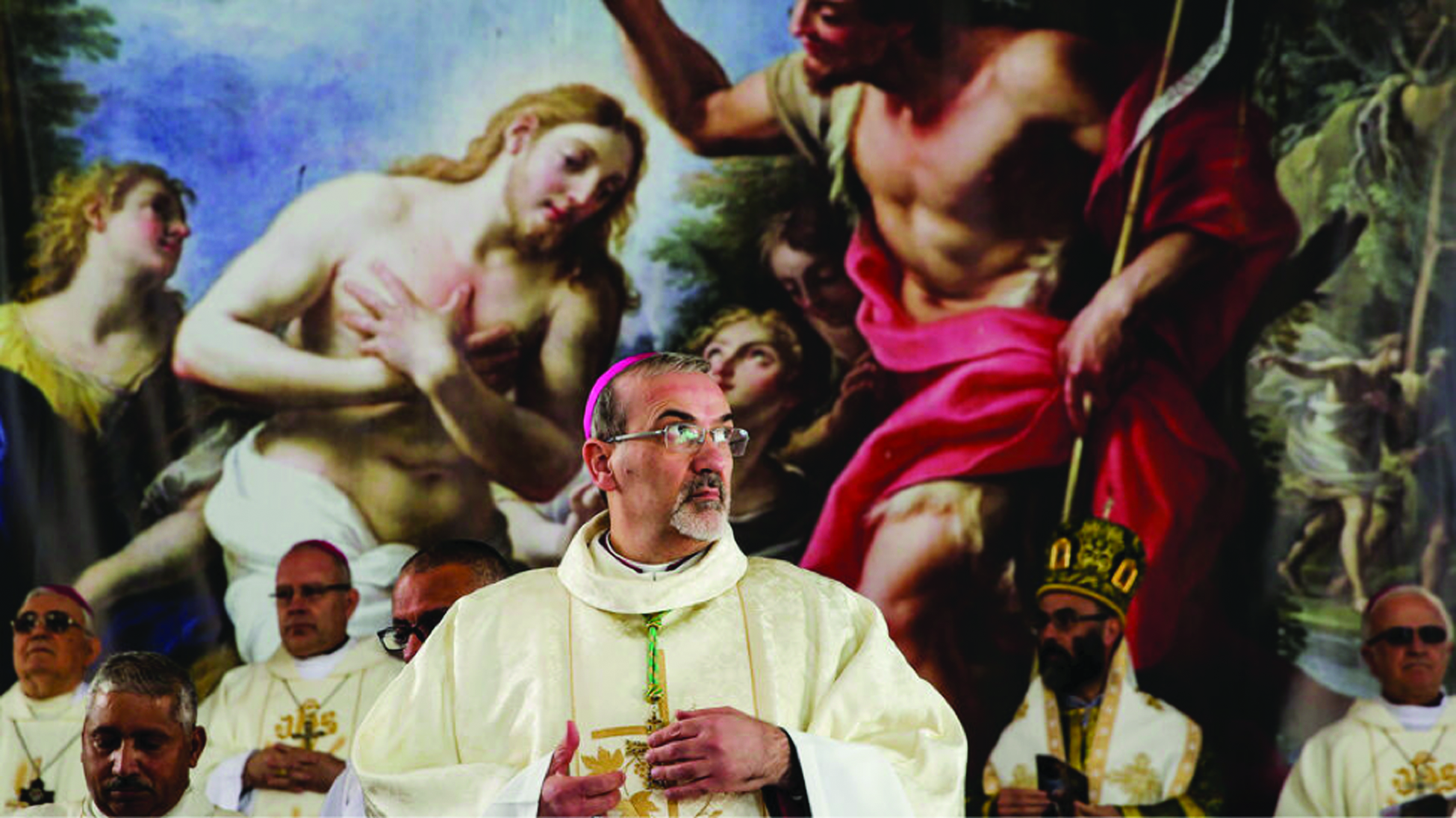

Workmen taking down the crucifix in San Marcello to install it in St. Peter’s Square for March 27’s unprecedented Urbi et Orbi blessing.

Like the Salus Populi Romani, the crucifix’s origin is not known except that it’s probably Tuscan and may date to the 15th century. As with the icon, the Romans are particularly devoted to it. For on the night of May 22, 1519 an earlier church dedicated to San Marcello was almost completely destroyed by fire; only this crucifix remained providentially intact. Then three years later, a terrible plague raged in Rome. The then-Cardinal Titular, to implore divine clemency, promoted a solemn penitential procession. The procession, which lasted 16 days, from August 4 to 20, passed through many Roman neighborhoods, and ended at St. Peter’s. Shortly thereafter, the plague ceased.

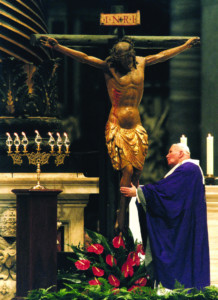

St. John Paul II celebrating the “Day of Forgiveness”

Since then the crucifix has been carried in procession to St. Peter’s Square every Roman Holy Year, normally every 50 years. Engraved on its back is the name of each pope who has witnessed these processions. The last name to be engraved is that of Pope St. John Paul II, who embraced the crucifix on the “Day of Forgiveness” during the Jubilee Year 2000.

Epilogue: Let’s hope that, in spite of rain damage to its paint and wood on March 27, the crucifix remains “miraculous” and that Our Lady answers Pope Francis’ prayer so he can go on his next two already-planned trips: to Indonesia, East Timor and Papua New Guinea in September of this year, and in 2022 to Portugal, where he already went in 2017, this time for World Youth Day.

Facebook Comments