On until April 27 in the Neoclassical, chandeliered Sala Bianca (White Hall) of the Palatine Gallery in Florence’s Pitti Palace, where fashion shows are usually held, is a first-of-its kind exhibition, “Una volta nella vita: Tesori dagli archivi e dalle biblioteche di Firenze” (“Once in a Lifetime: Treasures from the Archives and Libraries in Florence”). Its title was chosen on purpose by its Florentine Curator Marco Ferri, a Renaissance art historian and prolific author of books on Tuscany’s monuments and artworks, founder and director of Medicea. Rivista interdisciplinare di studi medicei (an interdisciplinary journal concerning the de’ Medici dynasty), cultural journalist for Il Giornale della Toscana, and since 2012 Head of Communications for Polo Museale Fiorentino (The Coordination Center of All Florentine Museums).

In the well-explained and well-illustrated catalog, published by Sillabe sadly only in Italian, but a bargain at 30 euro, he explains that many important artworks are on permanent display in museums and/or sometimes travel to temporary exhibits. In contrast, old books and historical documents are seldom on permanent display, if ever displayed at all, and usually don’t travel because their contents are limited to local interest.

Hence, Curator Ferri was determined to give the small sample of parchment and paper here their rightful recognition and importance and public attention at least once in their lifetimes.

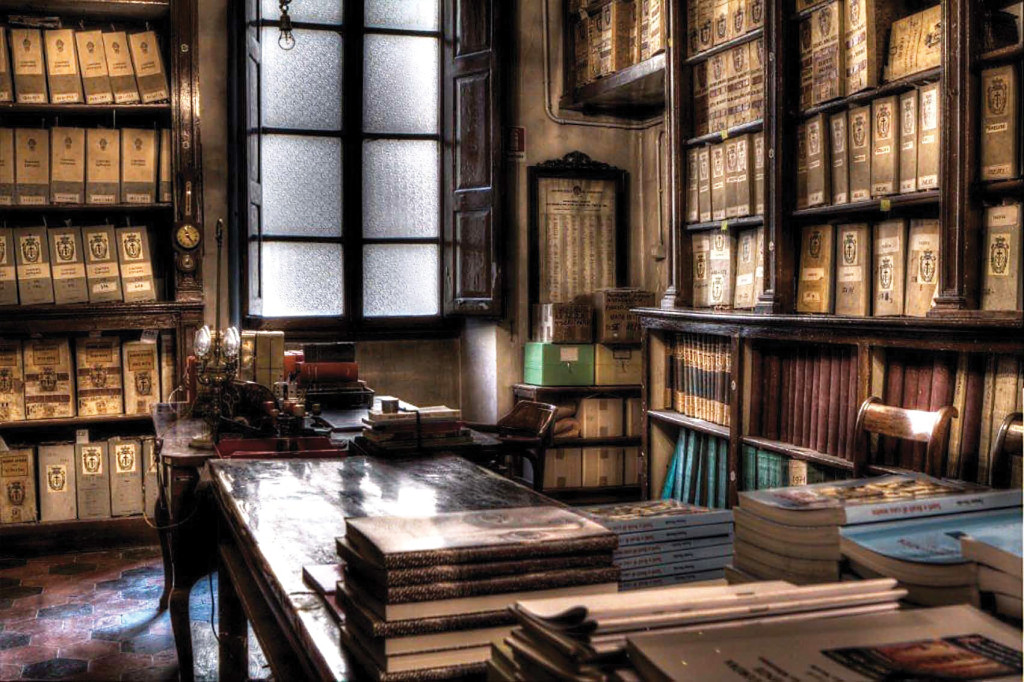

In fact, in this exhibition, the first in an exhibition cycle called “un anno ad arte” (“A year devoted to art”) many of the more than 130 items, all connected to Florentine history and conserved in Florentine institutions, have never been seen by the public before and they certainly have never before been displayed together. The papyrus, medieval illuminated manuscripts, printed books, historical documents, personal letters, drawings, and prints here are on loan from 33 public Florentine archives and libraries, many housed in historical buildings as interesting as their contents: State Archives, Archives of the Convent of Santissima Annunziata, Archives of the Venerable Archconfraternity of the Misericordia, The Historical Archives of Florence, The Archives of Buonomini di San Martino, The Historical Archive of Florentine Museums, The Archives dell’Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore (The Cathedral), The Archives dell’Opera di Santa Croce, The Guicciardini Archives, The National Library, Marucelliana Library, Laurentian Library, Riccardiana Library, The Library of the Uffizi Museum, The Library of the Conservatory “Luigi Cherubini,” The Moreniana Library, The University’s Biomedical Library, The Libraries of the Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze (The Savings Bank of Florence), The Library of the Galileo Museum, The Library of Seminario Arcivescovile Maggiore, The Library of the Società Dantesca Italiana, The Oblate Library, The Library of the Soprintendenza per i beni archeologici della Toscana, The Library of The Horne Foundation and Museum, The Archive and Library of the Casa Buonarroti (Michelangelo), Accademia della Crusca, The Archives of the Accademia degli Immobili, The Tuscan Academy of Science and Letters “La Colombaria,” Accademia dei Georgofili, The Archives dell’Istituto degli Innocenti, The Italian Army’s “Attilio Mori” Library housed in the Convent of the Santissima Annunziata, Gabinetto G.P. Viesseux, and Fondazione Spadolini Nuova Antologia.

In the catalog, the entry of each institution includes a photograph of the place and a page-long history before a few pages about the specific highlights with a photograph and history of each treasure.

The items are not displayed chronologically or by theme, but rather by institution in the order listed above. The oldest item is a papyrus of The Book of the Dead from ancient Egypt dating to c. 304-30 B.C. on loan from the Egyptian collection in Florence located in the city’s Archeology Museum under the jurisdiction of the Superintendence of Archeological Artifacts; the most recent are lithographs of sea views along the Tuscan coast by the poet Eugenio Montale (1896-1981), winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature 1975, bound in an album entitled Diario dal Forte dei Marmi and published in 1969 from the National Library not to mention a translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy into Vietnamese, its 279th language, in 2009 from The Dante Society.

As is clear from the list of the 33 institutions, several were originally and may still be ecclesiastical archives or libraries housed in convents. The oldest on Florence’s Cathedral Square is the Archive of the Archconfraternity of Misericordia, which was founded in 1244 by the Dominican monk, St. Peter the Martyr, as a protection against “Patarine” heretics. Apart from its armed defense of the Faith, the Archconfraternity soon started assisting the needy, caring for the sick, and burying the poor, activities it still does today. On display here is the register of its members from 1361-1527 and its illuminated statues written in the handwriting of Alessandro da Verrazano (the father of the explorer Giovanni, namesake of the bridge over New York’s “Verrazano Narrows” between Brooklyn and Staten Island) and dating to the early 1500s.

Other star items include Leonardo da Vinci’s Baptismal certificate (April 15, 1452) and the (1465) act of concession of King Louis XI of France to Piero de’ Medici to use the giglio (lily) of France in his coat-of-arms on loan from the State Archives; the first medical dictionary, Clavis Sanationis by Simone Cordo, the personal doctor of Pope Nicholas IV, printed in 1474 from the Biomedical Library of the University of Florence; a Register (1445-50) from the Istituto degli Innocenti citing the name of the first baby girl, Agata Smeralda, abandoned in this orphanage’s stone “wheel.”

Moreover, there is a Baptismal Register of baby boys from 1512-22 including Cosimo I de’ Medici’s on June 20, 1519 from the Cathedral’s Archives; a letter, probably dated September 29, 1495, from Savonarola to his most faithful follower Fra Angelo Maruffi asking for his prayers, and a 1526 Papal Bull of Clement VII complete with seal naming Francesco Guicciardini Lieutenant General of the Papal States from the Guicciardini Archive; an account of the transfer on March 12, 1737 of Galileo’s corpse to its present burial site in Santa Croce from that church’s archives; and Commentaries on Virgil by Servius Maurus Honoratus printed 1471-72 by the goldsmith Bernardo Cennini and his sons Domenico and Pietro, the first book to be printed in Florence with moveable type.

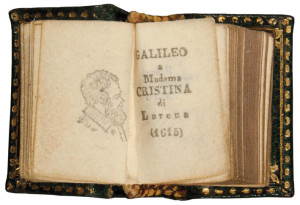

Galileo Galilei’s Letter to Madama Cristina di Lorena believed to be the smallest book in the world.

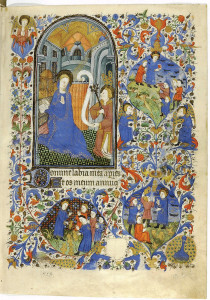

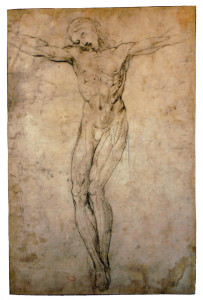

Also here: Galileo’s Letter’s to Madama Cristina di Lorena, published by Salmin in Padua in 1897 and considered to be the smallest printed book in the world, and the 1587 manuscript of his Due Lezioni all’Accademia fiorentina circa la figura, sito and grandezza dell’Inferno di Dante, all three texts from the National Library; a pen drawing of the Crucifixion by Raphael and very early printed books from the Marucelliana Library; several breath-taking illuminated manuscripts from the Ricciardiana Library; six copies of Dante’s The Divine Comedy (one printed in Venice in 1477 by Windeln of Speyer, another the first illustrated printed copy (1481) with drawings by Botticelli, and still another a three–volume edition of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s translation published in Boston from 1865-67 from the Library of Dante’s Society; and a small page with few sketches by Michelangelo of a Crucifixion which offers instructions on how to extract marble blocks from a quarry on loan from Casa Buonarroti.

The exhibition’s last case contains books from the National Library still covered in mud from when the Arno overflowed on November 4, 1966 as well as others irreparably damaged by the Mafia bomb of the Accademia dei Georgofili, (founded in 1753 and the oldest institution in the world devoted to agriculture, nutrition, and social development), in 1993, which killed a family of five.

“This exhibition,” wrote Renaissance art historian Cristina Acidini, successor of Antonio Paolucci (now Director of the Vatican Museums) as Florence’s Superintendent of Historical, Artistic, and Ethno-anthropological Patrimony, in the catalog’s introduction “is a ‘hymn to paper,’ which, even though we’re entering the third millennium, is not losing its critical role and vital importance.”

Facebook Comments