Over a Century Ago, the Priest and Writer Robert Hugh Benson Foresaw the Tremendous Rise of Secular Humanism… And the Contraction of the Catholic Church

By ITV Staff

Editor’s Note: The passage below is from the novel Lord of the World, written by the English Catholic convert Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson (the son of the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury) in 1907. He attempts a vision of the world more than a century in the future — in the early 21st century… our own time… predicting the rise of Communism, the fall of faith in many places, the advance of technology (he foresees helicopters) and so forth, up until… the Second Coming of the Lord, with which his vision ends. For this reason, and also because Pope Benedict and Pope Francis have repeatedly cited Benson’s book, saying its clarification of the danger of a type of humanitarianism without God is a true danger that we do face, we are printing selections from it in ITV, now and in the months ahead.

Editor’s Note: The passage below is from the novel Lord of the World, written by the English Catholic convert Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson (the son of the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury) in 1907. He attempts a vision of the world more than a century in the future — in the early 21st century… our own time… predicting the rise of Communism, the fall of faith in many places, the advance of technology (he foresees helicopters) and so forth, up until… the Second Coming of the Lord, with which his vision ends. For this reason, and also because Pope Benedict and Pope Francis have repeatedly cited Benson’s book, saying its clarification of the danger of a type of humanitarianism without God is a true danger that we do face, we are printing selections from it in ITV, now and in the months ahead.

Lord of the World

Lord of the World

By Robert Hugh Benson (1907)

Chapter IV (continued)

Part III

It was not until nearly two hours later that Percy was standing at the house beyond the Junction.

He had argued, expostulated, threatened, but the officials were like men possessed. Half of them had disappeared in the rush to the City, for it had leaked out, in spite of the Government’s precautions, that Paul’s House, known once as St. Paul’s Cathedral, was to be the scene of Felsenburgh’s reception. The others seemed demented; one man on the platform had dropped dead from nervous exhaustion, but no one appeared to care; and the body lay huddled beneath a seat. Again and again Percy had been swept away by a rush, as he struggled from platform to platform in his search for a car that would take him to Croydon. It seemed that there was none to be had, and the useless carriages collected like drift-wood between the platforms, as others whirled up from the country bringing loads of frantic, delirious men, who vanished like smoke from the white rubber-boards. The platforms were continually crowded, and as continually emptied, and it was not until half-an-hour before midnight that the block began to move outwards again.

Well, he was here at last, dishevelled, hatless and exhausted, looking up at the dark windows.

He scarcely knew what he thought of the whole matter. War, of course, was terrible. And such a war as this would have been too terrible for the imagination to visualize; but to the priest’s mind there were other things even worse. What of universal peace—peace, that is to say, established by others than Christ’s method? Or was God behind even this? The questions were hopeless.

Felsenburgh—it was he then who had done this thing—this thing undoubtedly greater than any secular event hitherto known in civilisation. What manner of man was he? What was his character, his motive, his method? How would he use his success?… So the points flew before him like a stream of sparks, each, it might be, harmless; each, equally, capable of setting a world on fire. Meanwhile here was an old woman who desired to be reconciled with God before she died….

* * * * *

He touched the button again, three or four times, and waited. Then a light sprang out overhead, and he knew that he was heard.

“I was sent for,” he exclaimed to the bewildered maid. “I should have been here at twenty-two: I was prevented by the rush.”

She babbled out a question at him.

“Yes, it is true, I believe,” he said. “It is peace, not war. Kindly take me upstairs.”

He went through the hall with a curious sense of guilt. This was Brand’s house then—that vivid orator, so bitterly eloquent against God; and here was he, a priest, slinking in under cover of night. Well, well, it was not of his appointment.

At the door of an upstairs room the maid turned to him.

“A doctor, sir?” she said.

“That is my affair,” said Percy briefly, and opened the door.

* * * * *

A little wailing cry broke from the corner, before he had time to close the door again.

“Oh! thank God! I thought He had forgotten me. You are a priest, father?”

“I am a priest.Do you not remember seeing me in the Cathedral?”

“Yes, yes, sir; I saw you praying, father. Oh! thank God, thank God!”

Percy stood looking down at her a moment, seeing her flushed old face in the nightcap, her bright sunken eyes and her tremulous hands.Yes; this was genuine enough.

“Now, my child,” he said, “tell me.”

“My confession, father.”

Percy drew out the purple thread, slipped it over his shoulders, and sat down by the bed.

* * * * *

But she would not let him go for a while after that.

“Tell me, father. When will you bring me Holy Communion?”

He hesitated.

“I understand that Mr. Brand and his wife know nothing of all this?”

“No, father.”

“Tell me, are you very ill?”

“I don’t know, father. They will not tell me. I thought I was gone last night.”

“When would you wish me to bring you Holy Communion? I will do as you say.”

“Shall I send to you in a day or two? Father, ought I to tell him?”

“You are not obliged.”

“I will if I ought.”

“Well, think about it, and let me know….You have heard what has happened?”

She nodded, but almost uninterestedly; and Percy was conscious of a tiny prick of compunction at his own heart. After all, the reconciling of a soul to God was a greater thing than the reconciling of East to West.

“It may make a difference to Mr. Brand,” he said. “He will be a great man, now, you know.”

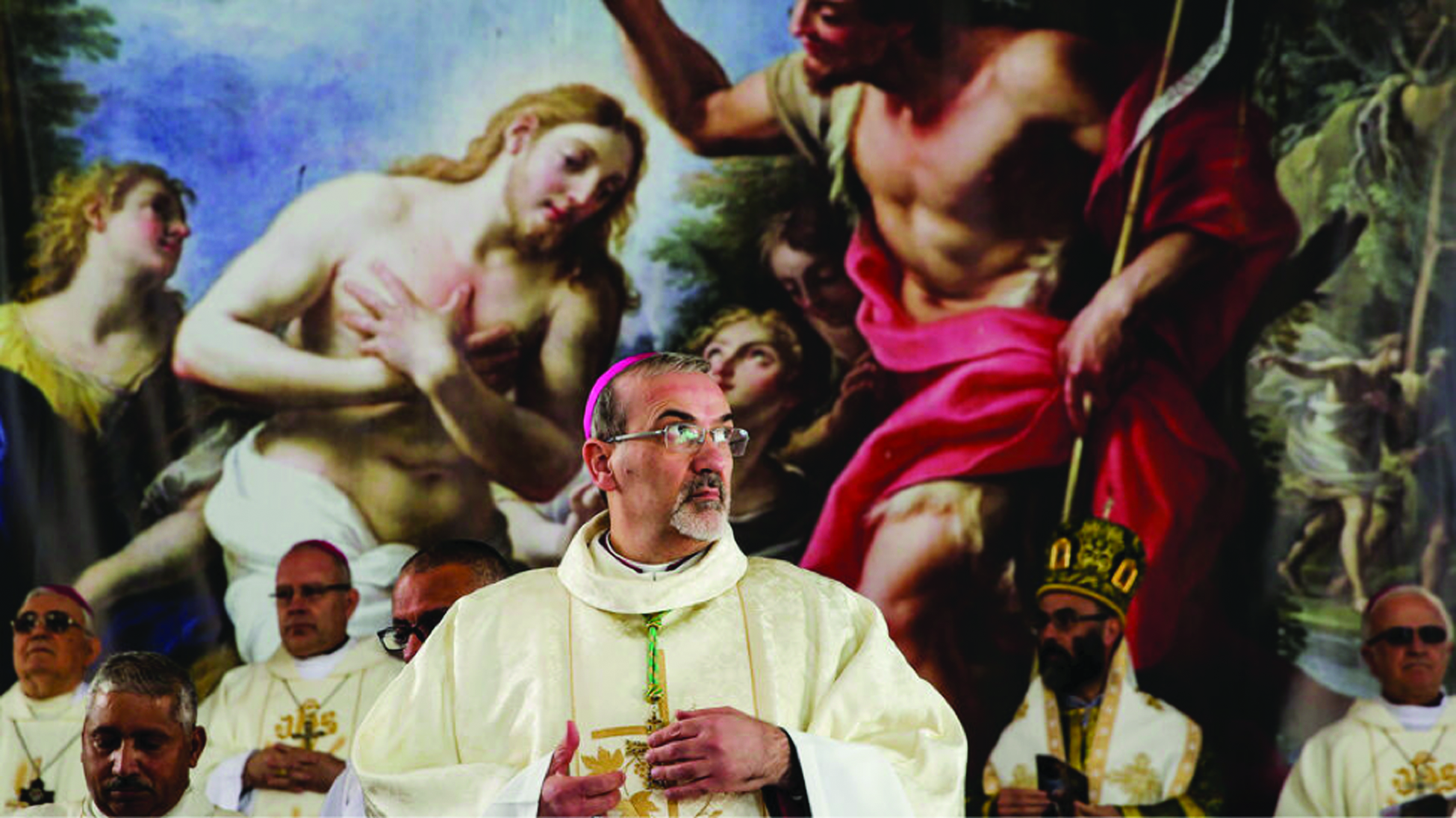

God as seen by William Blake as the Architect of the world, in Ancient of Days, held in the British Museum, London

She still looked at him in silence, smiling a little. Percy was astonished at the youthfulness of that old face. Then her face changed.

“Father, I must not keep you; but tell me this—Who is this man?”

“Felsenburgh?”

“Yes.”

“No one knows. We shall know more tomorrow. He is in town to-night.”

She looked so strange that Percy for an instant thought it was a seizure. Her face seemed to fall away in a kind of emotion, half cunning, half fear.

“Well, my child?”

“Father, I am a little afraid when I think of that man. He cannot harm me, can he? I am safe now? I am a Catholic—?”

“My child, of course you are safe. What is the matter? How can this man injure you?”

But the look of terror was still there, and Percy came a step nearer.

“You must not give way to fancies,” he said. “Just commit yourself to our Blessed Lord. This man can do you no harm.”

He was speaking now as to a child; but it was of no use. Her old mouth was still sucked in, and her eyes wandered past him into the gloom of the room behind.

“My child, tell me what is the matter. What do you know of Felsenburgh? You have been dreaming.”

She nodded suddenly and energetically, and Percy for the first time felt his heart give a little leap of apprehension. Was this old woman out of her mind, then? Or why was it that that name seemed to him sinister? Then he remembered that Father Blackmore had once talked like this. He made an effort, and sat down once more.

“Now tell me plainly,” he said. “You have been dreaming.What have you dreamt?”

She raised herself a little in bed, again glancing round the room; then she put out her old ringed hand for one of his, and he gave it, wondering.

“The door is shut, father? There is no one listening?”

“No, no, my child. Why are you trembling? You must not be superstitious.”

“Father, I will tell you. Dreams are nonsense, are they not? Well, at least, this is what I dreamt.

“I was somewhere in a great house; I do not know where it was. It was a house I have never seen. It was one of the old houses, and it was very dark. I was a child, I thought, and I was … I was afraid of something. The passages were all dark, and I went crying in the dark, looking for a light, and there was none. Then I heard a voice talking, a great way off. Father—-”

Her hand gripped his more tightly, and again her eyes went round the room.

With great difficulty Percy repressed a sigh. Yet he dared not leave her just now. The house was very still; only from outside now and again sounded the clang of the cars, as they sped countrywards again from the congested town, and once the sound of great shouting. He wondered what time it was.

“Had you better tell me now?” he asked, still talking with a patient simplicity. “What time will they be back?”

“Not yet,” she whispered. “Mabel said not till two o’clock. What time is it now, father?”

He pulled out his watch with his disengaged hand.

“It is not yet one,” he said.

“Very well, listen, father…. I was in this house; and I heard that talking; and I ran along the passages, till I saw light below a door; and then I stopped…. Nearer, father.”

Percy was a little awed in spite of himself. Her voice had suddenly dropped to a whisper, and her old eyes seemed to hold him strangely.

“I stopped, father; I dared not go in. I could hear the talking, and I could see the light; and I dared not go in. Father, it was Felsenburgh in that room.”

From beneath came the sudden snap of a door; then the sound of footsteps. Percy turned his head abruptly, and at the same moment heard a swift indrawn breath from the old woman.

“Hush!” he said. “Who is that?”

Two voices were talking in the hall below now, and at the sound the old woman relaxed her hold.

“I—I thought it to be him,” she murmured.

Percy stood up; he could see that she did not understand the situation. “Yes, my child,” he said quietly, “but who is it?”

“My son and his wife,” she said; then her face changed once more. “Why—why, father—-”

Her voice died in her throat, as a step vibrated outside. For a moment there was complete silence; then a whisper, plainly audible, in a girl’s voice.

“Why, her light is burning. Come in, Oliver, but softly.”

Then the handle turned.

(End Chapter IV, Part 3; next month, Chapter V)

Facebook Comments